Case of the SouthAuthor Sketch

|

Saving Communities

|

|||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

Get Involved |

The Case of the South Against the

North

The Case of the South Against the

North

Or

Historical Evidence Justifying the Southern States of the American

Union in their Long Controversy with the Northern States

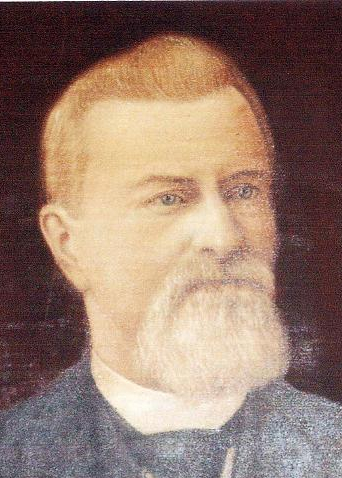

Benjamin Franklin Grady,

A Representatative in the Fifty-Second and Fifty-Third Congresses of

the United States

EDWARDS & BROUGHTON, PUBLISHERS,

RALEIGH, N. C., 1899

CHAPTER I.

FALSE DEFINITIONS THE CHIEF SUPPORT OF THE FALSE DOCTRINES WHICH DESTROYED THE PEACE OF THE UNION.

"Contemporanea expositio est optima et fortisima in lege."1

- Wharton's Legal Maxims.

If we carefully examine the long controversy between the two sections of the Federal Union with the object of satisfying ourselves as to the validity of the reasoning, the arguments, and the appeals to the intelligence of the people relied on by the respective disputants - disregarding mere appeals to self-interest and passion - we shall find that in their last analysis they were nothing but differences of interpretation. The fundamental difference, from which all others logically resulted, was about the significance of the terms employed to name or describe the Colonies and their inhabitants after the 4th of July, 1776. One class of politicians maintained that each one of the States was an independent sovereignty; that the Federal Government was nothing more than an agent of the States, created by them for certain well-defined purposes; and "that whenever this agent usurped powers not granted to it by the States, they were no longer bound to regard it as their agent; and that, furthermore, a violation of the mutual covenants of the States, solemnly "nominated in the bond," would absolve an injured State from its obligations as a member of the Confederacy. The opposing school of politicians denied the sovereignty of each State; insisted that "the people of America" united themselves in a social compact without regard to State lines, that they, as "one people," organized a "National Government" to manage the affairs of the whole people, and "local" governments to which were entrusted local interests - in short, that the "National Government" representing the sovereignty of the whole people, is paramount to the local or State governments.

These conflicting views led to deplorable consequences; and since it is important that we should be able to ascertain where the responsibility lay, let us apply the test of definition. This may not be infallible, but it is the test which the common sense of mankind has decided to be "best and strongest."

The four most important of these terms are (1) State, (2) sovereign, (3) citizen, and (4) nation.

For the true meaning of this word, when applied to communities or governments, we have the authority of statesmen, scholars, historians, jurists, and poets who lived and wrote during the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, including the formative period of our Union. Here are some of them:

(a) Lord Bacon (who died 1626) in his essay "Of Great Place," begins. thus: "Men in great place are thrice servants - servants of the sovereign or State," etc.; and in his essay "Of Seditions and Troubles," he says: "As there are certain hollow blasts of wind and secret swellings of the seas before a tempest, so are there in States"; and, again, "Libels and licentious discourses against the State, when they are frequent and open: and in like sort false news, often running up and down, to the disadvantage of the State, and hastily embraced, are amongst the signs of troubles." All through his writings "State" is a synonym for the highest form of an organized community.

(b) Dr. Thomas Fuller (died 1661) is quoted thus in Richardson's Dictionary (under "State"): "The word statesman is of great latitude, sometimes signifying such who are able to manage offices of state, though never actually called thereto."

(c) Sir Matthew Hale (died 1676) is quoted by Blackstone (first chapter of his fourth book) as' saying: "When offenses grow enormous, frequent, and dangerous to a kingdom or State," etc.

(d) Boyer's French-English and English-French Royal Dictionary, published in Amsterdam in 1727, defines "State" thus: "(A. country living under the same government) Etat," etc.; and, again, "(the government of a People Living under the Dominion of a Prince, or in a Commonwealth) Etat, Empire, Souverainete, ou Republique."

(e) David Hume (died 1775) says on page 138 of Volume III of his History of England: "Most of the arts and professions in a State are of such a nature, that while they promote the interests of the society, they are also useful or agreeable to some individual"; and, again, "But there are also some callings which though useful and even necessary in a State, bring no particular advantage or pleasure to any individual." All through his volumes the word is used as it is here.

(f) Sir William Blackstone (died 1780) says in the chapter already referred to, that a knowledge of the criminal law "is of the utmost importance to every individual in the State"; that the law and its administration "may be modified, narrowed, or enlarged according to the local or occasional necessities of the State"; and that "sanguinary laws are a bad symptom of the distemper of any State."

(g) Adam Smith (died 1790) says in his Wealth of Nations, Volume II, page 62: "In the plenty of good land the European colonies established in America and the West Indies resemble and even greatly surpass those of ancient Greece. In their dependency upon the mother State they resemble those of ancient Rome."

(h) And Sir William Jones (died 1794)-wrote

"What constitutes a state?

Not high-raised battlements or labored mound,

Thick wall or moated gate;

Not cities proud, with spires and turrets crowned;

Not bays and broad-armed ports,

Where, laughing at the storm, rich navies ride;

Not starred and spangled courts,

Where low-browed baseness wafts perfume to pride.

No! Men - high-minded men.

* * * * * *

These constitute a state;

And sovereign law, that state's collected will,

O'er thrones and globes elate

Sits empress," etc.

It is beyond dispute, therefore, that in 1776 "State," whether applied to a people or to their government, was a general term, while "kingdom," "empire," "republic," and "commonwealth" were specific terms, denoting sources of political power. It was a more comprehensive term than either of these. It was so understood by the statesmen who put "the State of Great Britain" in the Declaration of Independence; it was so understood by the Colonies when, through their delegates in the Continental Congress, they declared themselves to be "free and independent States; it was so understood by their delegates when they set forth "the necessity which constrains them (the Colonies) to alter their former systems (plural) of government"; it was so understood by the negotiators of the Treaty of Peace of 1783, when they wrote:

"His Britannic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz: New Hampshire, Massachusetts-Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia to be free, sovereign and independent States"; and, again, when they penned the declaration: "There shall be a firm and perpetual peace between his Britannic Majesty and the said States"; it was so understood by Massachusetts when she declared herself to be a "free, sovereign, and independent State," although she had adopted "Commonwealth" as her distinctive title; it was so understood by the Continental Congress when it placed this second Article in its plan of union: "Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence," etc.; it was so understood by the same body when they recognized the Congress as a Congress of States - "the United States in Congress assembled"; it was so understood by the people of New Hampshire when, in their Constitution of 1792, they declared: "The people of this State have the sole and exclusive right of governing themselves as a free, sovereign and independent State"; it was so understood by the people of Vermont when, in their Constitution of 1793, they required "every officer, whether judicial, executive or military, in authority under this State, before he enters upon the execution of his office," to "take and subscribe the following oath or affirmation of allegiance to this State, unless he shall produce evidence that he has before taken the same," etc.; it was so understood by the States when they defined "treason against a State," and their delegates provided for the surrender of any "person charged in any State with treason"; it was so understood by the Congress of the Confederation when, using a practically synonymous word in the Thirteenth Article of the Ordinance for the Government of the Northwest Territory, they said (July 13, 1787, while the Constitutional Convention was in session): "And for extending the fundamental principles of civil and religious liberty, which form the basis whereon these republics,2 their laws, etc., are erected," etc.; it was so understood by the Convention of 1787, which closed its draft of the Constitution with the statement that it was "done in Convention by the unanimous consent of the States present"; and it was so understood by the Congress in 1794, when in framing the Eleventh Amendment they proposed to shield the States against suits prosecuted by "citizens or subjects of any foreign State."

This long line of authorities reaching back beyond 1626, can leave no doubt in the minds of intelligent persons that each one of the States was regarded by itself and by the other States as an independent sovereignty, possessing all the rights, powers and jurisdictions of any other sovereignty; that it could form "a firm league of friendship" with any or all of the other States, or refuse to do so.

When, we may now ask, did they lose their character as States? When did "State" lose its proper meaning? Was it done by one act, or was the operation gradual? The answer to these questions is that it was never done at all up to 1861.

The claim that it was done when they united in 1776 for their mutual defense, is negatived by the second Article of the Articles of Confederation adopted afterwards; and the assertion that it was done by the first three words of the preamble of the Constitution - "We, the people" - is disposed of by the declaration that the Constitution was to be "between the States." Equally unfounded is the claim that the people of all the States were consolidated into a Nation because the Constitution was to be the supreme law of the land. Treaties also were to be the supreme law of the land; and, unquestionably, if the construction of the consolidationists were correct, both parties to a treaty would be sovereigns over the States: The truth is, this was simply another way of declaring. as the Articles of Confederation did, that "each State shall abide by thy' determinations of the United States in Congress assembled on all questions which by this Confederation are submitted to them"; that "the Articles of this Confederation shall be inviolably observed by every State "; and that "the Union shall be perpetual."

The term

sovereign is properly an

adjective, being a modern form of the ancient Latin word supremus, which we translate

highest. In the course of time it came to be used also as a noun,

signifying the man possessing the supreme or highest authority in a

State. This was its meaning during the seventeenth century. It was its

meaning when these thirteen Colonies freed themselves from British

rule. And it is its meaning to-day in monarchical governments.

When, however, the sovereignty of the British king was successfully renounced by these Colonies, the new order of things inevitably led to some confusion of thought, because, strictly speaking, nobody had inherited the sovereignty of the king, who, as to them, was dead. Was each inhabitant a sovereign? Was each State a sovereign? Or were all the people of all the States a sovereign? Naturally the answer to these questions would depend on the answer to the question, What had become of the allegiance each inhabitant had owed to the British crown? Did he owe anything of the sort now; and, if he did, to whom?

This question was easily answered; each one of the Colonies, after active hostilities began between them and the British Government, and more than a year before the Declaration of Independence, demanded the allegiance of each one of its inhabitants, and in default of compliance the property of recusants was confiscated by the legislatures.3

This was done in every one of the States, and the right was denied by nobody except the British and the Tories.

Hence it followed necessarily that, if the word sovereignty was at all admissible in the new nomenclature, it belonged to each State; and, accordingly, in all the early State Constitutions, in the Declaration of Independence, and in the Articles of Confederation, the sovereignty of the several States is recognized as the logical sequence of Independence.

This

sovereignty was never

renounced, or delegated, or surrendered by the States; they delegated

powers, jurisdictions, etc., but this was no more a delegation of

sovereignty than the conferring of powers on a tenant transforms him

into a landlord.4

This word is

derived from city, as

burgess or burgher is from borough or burg, but for some reason, unlike

burgess, it was in the course of time applied to members of any

community or body politic, and became the opposite of foreigner. The

rights and the duties of the citizen depended on the degree of

civilization attained to by his community and the nature of the

government, and there could be no inference from the word itself as to

the privileges and immunities of the person to whom it was applied,

whether a man, or a woman, or a child.

In the course of time it became in England and France the equivalent of inhabitant, as the lexicographers inform us, and as we may infer from its use in the Bible where it is found in four places, as follows:

1. Luke xv, 15: "And he went and joined himself to a citizen of that country"

2. Luke xix, 14: "But his citizens hated him, and sent a messenger after him, saying, We will not have this man to reign over us."

3. Acts xxi, 39: "But Paul said, I am a man which am a Jew of Tarsus, a city of Cilicia, a citizen of no mean city."

4. Ephesians ii, 19: "Now, therefore, ye are no more strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints, and of the household of God."

"In France," says Alden's Cyclopcedia, "it denotes any one who is born in the country, or naturalized in it."

Such was the meaning of this term in our Revolutionary period, and in what may be called the formative stages of a nomenclature suited to our new and untried conditions.5

Hence the sharp line of distinction between royal and popular governments had the king on one side and "the people" on the other; and in all the early documents the word "citizen" is of minor importance.

1. In the Mecklenburg

Declaration of

Independence (May 20, 1775) the word does not occur.6 [This

is an apocryphcal document.]

2. In the Mecklenburg Resolves (May 31, 1775) it is not found.7

3. In the Declaration of Independence (Jul7 4, 1776) "fellow citizens'' occurs once, "inhabitants" twice, "free people" once, and "the people" twice.

4. In North Carolina's Constitution (1776) "freemen" appears eight times, "the people" eight times, "inhabitants" five times, and "free8 citizens" once.

5. In the Articles of Confederation (framed 1777) the people are called "free inhabitants" once, "free citizens" once, "inhabitants" twice, "the people" twice, and "members" of a State once; and, as if it was intended to leave no ground for misconception, article 4 says: "The free inhabitants of each of these States... shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States."

It is clear enough, therefore, that in all the Constitutions the "fathers" applied the word citizen to every man, woman or child in the States; whether "free" or not; and that the declaration in the Fourteenth Amendment that "all persons born in the United States are citizens thereof" was the work of a set of statesmen who were ignorant of the first principles on which our Federal system was founded.

The word nation comes to us from the Latin language, and its etymological meaning is family, stock, or race. In this sense it was properly applied to the Indian tribes in the early days, as the Five Nations, the Six Nations, etc.

In the course of time, as races became intermingled, the word lost its proper significance, and separate communities were called nations, just as "jus gentium" - the law or right of families - now means the law of nations; but there was nothing in the word itself indicating the nature of the social or political institutions of the people it was applied to.

Hence, when these Colonies entered into united resistance to British aggressions or threatened aggressions, their people began to be regarded by the world as a nation; and with no great impropriety they have been called a nation ever since. The language contained no other word which could distinguish them from "foreign nations," as it contained no other term applicable to the Swiss, who for ages were divided into independent cantons, united together for no purpose but mutual defense.9

In the treaty of amity and commerce concluded between the United States and France, in 1778, "the two parties" are called "the two Nations"; and during the period of the Confederation all writers and speakers applied the word "nation" to the peoples of these States, although in the Articles "each State retained its freedom, sovereignty, and independence"; but when it was proposed to put "nation" in the Constitution, "the fathers" scented danger, and the proposition was rejected. In the progress of events, however, as the necessity arose for justifying some intended or actual infringement of the rights of certain classes or sections of the people, it began to be held that since the people of these States are a nation, it was the duty of the minority to submit to the will of the majority; and after awhile a majority of the "nation" - spelled then with a capital N - became thoroughly indoctrinated in this unfounded construction of the provisions of the Federal Constitution. The ignorance of the people was taken advantage of; such a fact as that Nevada has as much control over legislation as New York, and, in the event of a failure of the electors to choose a President, an equal voice in the election of that officer, was carefully hidden from the people; and at last the administration of the Government became, in their eyes, as national as that of Great Britain. But the mischief did not stop here; the Northern States became the Nation after the war of Secession commenced. It is a familiar sight to see in a newspaper published in one of them the statement that when Sumter was fired on "the Nation flew to arms." It appeared in the New York World as late as the last week in February, 1898.

There is nothing in the Constitution requiring or empowering a majority of the "nation" to elect or control any department or officer of the Government. Mr. Lincoln was chosen by 39 per cent of the aggregate popular votes of the States; it is easily possible for a majority of the Senators to represent a minority of the whole people; a majority of the Representatives can be elected by a minority; and the Judges of the Supreme and other courts may be appointed by a minority President and confirmed by a minority Senate.10

On the solid foundation of these definitions a body of political doctrines was erected which can never be demolished, and they were never attacked by any respectable party until it became necessary to defend encroachments on the rights of certain States. In the course of time there was a union of all the interests which had been quartered on the people, and of others which hoped to be so quartered, and also of ignorant and fanatical reformers who proposed to use the machinery of the Federal Government to further their schemes; and by the assistance of demagogues, a venal press, and honest but misinformed friends of the Union, they succeeded in establishing a new and powerful school of politicians who denied the truth of History, instilled vicious doctrines into the minds of the people, and prepared the way for the war between the sections.

1. Contemporaneous exposition is best and strongest in law.

2. A "republican government is that in which the body, or only a part of the people, is possessed of the supreme power." —Montesquieu's Spirit of Laws, Book II, Chapter I.

3.In

November 1777, the Legislature

of North Carolina, in session at

Newbern, passed an act, "That all the lands, tenements, etc., within

this State, and all and every right, etc., of which, any person was

seized or possessed, or to which any person had title, on the 4th of

July, in the year 1776, who on the said day was absent from this State,

and every part of the United States, and who still is absent from the

same; or who hath at any time during the present war attached himself

to, or ailed or abetted the enemies of the United States, etc., shall

and are hereby declared to be confiscated to the use of this State;

unless," etc.—Laws of North Carolina, Potter, Taylor and Yancey's

Digest, Volume 1. page 366.

4. By an apparent oversight the Constitution conferred on the Supreme Court the power to decide suits "between a State and citizens of another State." Under this provision a suit was instituted against Massachusetts, while John Hancock was Governor, which is thus referred to in Conrad's Lives of the Signers, etc., page 62.

"He (Hancock) did not, however, in favoring a Confederate Republic, vindicate with less scrupulous vigilance the dignity of the individual States. In a suit commenced against Massachusetts, by the Court of the United States, in which he was summoned upon a writ, as Governor, to answer the prosecution, he resisted the process, and maintained inviolate the sovereignty of the Commonwealth. A recurrence of a similar collision of authority was, in consequence of this opposition, prevented by an amendment (the Eleventh) of the Federal Constitution."

5. There was an attempt to give a new meaning to the word citizen in the Fourteenth Amendment. It says: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."

What the intention was is not clear; and there was a serious oversight, if the word was intended to imply come new relation to the Federal Government, since it excludes people who live in the Territories or in the District of Columbia.

6. Wheeler's History of North Carolina, Volume I, page 69.

7.

Ibid. 255.

8. This word "free" shows what was in the minds of the "fathers."

9.

Mr. Jefferson, February 8, 1786,

wrote to Mr. Madison: "The politics

of Europe render it indispensably necessary that with respect to

everything external we be one nation only, firmly hooped together.

Interior government is what each State should keep to itself."

10. If the reader will turn to the census tables he will find that there are 23 States, including the "mining camps," whose aggregate population is 11,597,263, or about 18 per cent of the total population of the States. These States send 46 Senators—a majority of two—to the Congress; and, if political parties were nearly equal in strength in these States, their Senators might represent less than 10 per cent of the population of the "Nation." And he will also see that the aggregate population of Montana, Wyoming, Nevada and Idaho is less than half (about 42 per cent) of the population of West Virginia, although they have as many (four) Representatives in Congress as that State has.

Comments. We are looking for comments that generate more light than heat. Please avoid grandstanding:

Saving Communities

420 29th St.

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263