Case of the SouthPreface

|

Saving Communities

|

|||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

Get Involved |

Or

Historical Evidence Justifying the Southern States of the American

Union in their Long Controversy with the Northern States

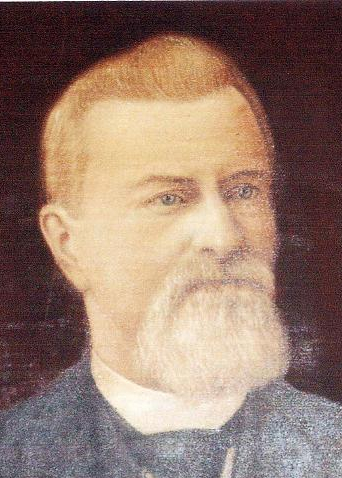

Benjamin Franklin Grady,

A Representatative in the Fifty-Second and Fifty-Third Congresses of

the United States

EDWARDS & BROUGHTON, PUBLISHERS,

RALEIGH, N. C., 1899

A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF THE AUTHOR.

It is not easy for a man to say much about himself without indulging

somewhat in self-laudation; hence this sketch shall be short It may be

considered a piece of vanity that I write at all; but I do so solely to

gratify the natural desire we all have to know something of the author

of a book which claims our attention.

I was horn October 10, 1831, on a farm in Duplin County, North Carolina. My great-great grandfather, on my father's side, was an Irishman who came to North Carolina about the middle of the eighteenth century. By intermarriages his blood in my veins is mingled with that of the Whitfields, Bryans, Outlaws and Sloans.

All these families were Whigs during the Revolutionary war; and they were advocates of what was called "strong government" in 1788-'89. Most of them, however, if not all, gradually drifted toward Jefferson's exposition of the powers of the Federal Government; and my father, Alexander Outlaw Grady, became a disciple of John C. Calhoun in 1832-'33, after hearing that statesman defend his position before the General Assembly of North Carolina, of which my father was a member. In 1860-'61 he was a secessionist.

My boyhood days were spent on the, farm, where I worked with the slaves during nine months of each year, and attended a three-months school in the winter. When I was about eighteen years of age I began to attend high schools, and after studying four years at the University of North Carolina I received the degree of A.B. in 1857.

I then taught for two years in Grove Academy, Kenansville, N. C., associated with Rev. James M. Sprunt, the gentleman who prepared me for entrance into the University. At the end of this period I was elected Professor of Mathematics and the Natural Sciences in Austin College, then located in Huntsville, Texas. I taught there till the war caused the college to suspend operations. About that time I had what my physician called the typhoid fever, which disabled me for active work till the early months of 1862. Then I joined a cavalry company which was organizing for the Confederate military service, which became Company K in the Twenty-fifth Regiment. We were soon dismounted, however, by the order of General Hindman, and served ever afterwards as infantry. At Arkansas Post, January 11, 1863, the whole command to which I was attached was captured, and we were all sent to Camp Butler, near Springfield, Illinois, where we were imprisoned for about three months. The rigors of winter in that latitude, against which our thin Southern clothing afforded us insufficient protection, prostrated nearly all of us with diseases; but in a short time a supply of blankets and woolen clothing came to us from some ladies of Missouri and Arkansas, and improved our condition very much.

Prison life was rather monotonous; but there was occasionally a little stir among us produced by an exhibition of authority by a small fellow called Colonel Lynch, who was our master. On one occasion he had us all rushed out of the barracks, and into line, and while one set of his underlings were searching our sleeping places - for "spoons," perhaps - another set were searching our persons for money. On another occasion a detail of us, including myself, were ordered out by this little tyrant to shovel snow out of his way - not out of ours. And when we got on the cars to leave the place, he sent men through each coach with orders to rob us of everything we had except what we had on our backs and one blanket apiece.

Exchanged about the middle of April, I was sent to General Bragg's army at Tullahoma, Tenn., in which I served till the close of the war in Granbury's Brigade, Cleburne's Division, Hardee's Corps, participating in all the skirmishes and battles (except at Nashville and at Bentonville) in which my Brigade was engaged. I was twice wounded - in my face and through my right hand - in the charge on the enemy's main line of breastworks, November 30, 1864, at Franklin, Tenn., and not many yards from where Cleburne and Granbury fell. I had been in what appeared to be more dangerous places, as at Chickamauga, September 19 and 20, 1863; at Missionary Ridge, where Cleburne's Division defeated Sherman's flanking column while Bragg's main army was being routed by Grant, November 25, 1863; at Ringgold, where Cleburne's Division repelled the repeated assaults of the troops of Sherman and Hooker from daylight till 2 o'clock in the evening, thus enabling the wagons, artillery, etc., of our army to get out of the reach of these invaders, November 27, 1863; at New Hope church, where Granbury's Brigade, assisted by one of General Govan's Arkansas regiments, defeated and drove off the ground Howard's Fourth Army Corps, wnich was attempting to flank Jo. Johnston on his right, May 27, 1864; at Atlanta, where a prolonged seige exposed us to danger day and night, etc., etc. But I had never received a scratch before.

After Hood's disastrous campaign in Tennessee we went to the northern part of Mississippi, from there by railway to Mobile, from there by water and railroad to Montgomery, and from there, partly on foot and partly on the few pieces of railroad which Sherman's vandals had not destroyed, we came to North Carolina to assist in repelling Sherman.

On the 19th of March, 1865, while the cannon were booming at Bentonville, and my command preparing to leave the railroad for the scene of action, I was sent by our surgeons back to Peace Institute Hospital in Raleigh, where typhoid fever kept me till May 2.

Without money, without decent clothing, and suffering from the effects of the fever, I went to my father's, and obtaining employment in the neighborhood at my chosen profession. I waited on him in his last sickness and saw him die of a broken heart1 in the year 1867, having survived the war and lived to see the black shadow of "reconstruction" and government by the ex-slaves hovering over his beloved Southland.

I remained in North Carolina, teaching until 1875, most of the time in Clinton, Sampson County. Then my health failing, for lack of sufficient exercise, I abandoned teaching, and went to farming. On the farm my life was not eventful; indeed I had no opportunity to distinguish myself as a farmer. I was appointed a Justice of the Peace in 1879, and in 1881 I was elected Superintendent of Public Instruction for my (Duplin) County, and held that position for eight years.

In 1890 and again in 1892 I was elected to represent the Third North Carolina District in the Congress of the United States.

I did not agree with my father regarding the policy of nullification or of secession. While I subscribed to the doctrine that no State in the Union had ever relinquished the right to be its own judge of the mode and measure of redress whenever its welfare and its peace should be put in jeopardy by the other States, acting separately or jointly, I doubted whether the nullification of a Federal act was consistent with the obligations imposed by the "firm league of friendship" with the unoffending States, if any; and I held that South Carolina should have set a better example than Massachusetts had, and submitted to the tariff as other States did whose interests were identical with her own, and united with them in appeals for justice to the people of the offending States.

As to secession, I believed it to be the best for the Southern States to remain in the Union, and trust to time and the good sense of the intelligent people of the Northern States for justice to themselves and their children. This hope was strengthened by the circumstance that the interests of the expanding West being identical with those of the South, the time was not far distant when that section would join the South in the struggle for riddance from the burdens imposed by the shipping, fishing, commercial and manufacturing States of the East.

This was the stand I took and held until Mr. Lincoln compelled me to choose whether I would help him to trample on the Constitution and crush South Carolina, or help South Carolina defend the principles of the Constitution and her own "sovereignty, freedom and independence." I went with South Carolina as my forefathers went with Massachusetts when "our Royal Sovereign" threatened to crush her.

B. F. GRADY.

Turkey, N. C., November, 1898.

1 Two of his

sons had been killed in the war, one at Bristoe Station and

the other at Snicker's Gap, both in Virginia; and the only remaining

son - the youngest - besides myself, had lost the thumb and two fingers

of

his right hand.

We are interested in comments and

questions that lead to light, not heat. Please refrain from grandstanding.

Preface |

Chapter 1 |

Contents |

Saving Communities

420 29th St.

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263