Case of the SouthChapter 1

|

Saving Communities

|

|||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

Get Involved |

The Case of

the South Against the

North

The Case of

the South Against the

North

Or

Historical Evidence Justifying the Southern States of the American

Union in their Long Controversy with the Northern States

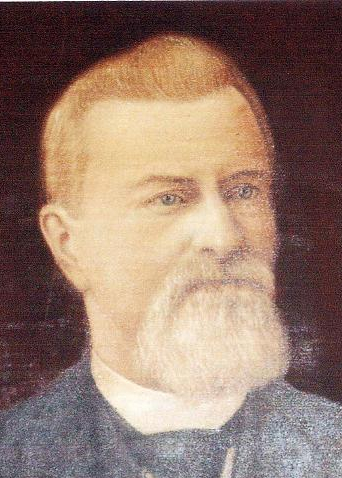

Benjamin

Franklin Grady,

A Representative in the Fifty-Second and Fifty-Third Congresses of

the United States

EDWARDS & BROUGHTON, PUBLISHERS,

RALEIGH, N. C., 1899

CHAPTER II.

THE UNION OF THE STATES - ITS OBJECTS, CONDITIONS AND LIMITATIONS.

Having defined the terms which will constantly recur in our discussion, the object in view demands as a next step a clear understanding of the relations of the States to each other after they had entered into a Union, the extent and the limitations of the powers they conferred on any department or officer of the Government which they established, and of the duties or mutual obligations they severally imposed on themselves.

Obviously the opinions and purposes of individuals, which change as knowledge expands and experience enlarges, deserve no place in the solution of such a problem as this; our only trustworthy guide is the action of each Colony in its own legislative assembly, or through its Representatives in the Continental Congress, and, after it became a State, through its delegates in the Congress of the Confederation, in the Constitutional Convention, and in its own Convention called to consider the new Constitution.

No argument is needed to prove that, if the people of any State were induced to adopt the Constitution by misrepresentations of the functions of the Government to be established and the scope of its powers, a fraud was practiced on them; nor was there any fraud. The objects of the framers of the Constitution, and the safe-guards against usurpation were honestly and truthfully presented to the people of the several States by the ablest statesmen in all of them, each article, section and clause of the instrument being explained according to the obvious meaning of the words and, the accepted canons of interpretation. And, for greater security to the States and their respective peoples, since experience had taught mankind that governing bodies are prone to exercise powers not belonging to them, a widespread demand led to such amendments as were thought to remove all danger.1

The

Convention which met in

Philadelphia on May 25, 1787, composed of delegates from all the States

except New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut and Maryland (though

delegates from all of these except Rhode Island appeared in a month or

two), and closed its labors on the 17th of September following, after

nearly four months of anxious and sometimes almost hopeless efforts to

compromise the conflicting interests of States and groups of States,

and agree upon a plan which would probably be ratified by the States,

transmitted to the Congress of the Confederation the draft of a

Constitution to be submitted to Conventions to be called in the

several States by their Legislatures at the request of the Congress.

[The proposed Constitution was never submitted to the Continental

Congress as instructed, but was submitted directly to the states.]

There were 13 States in the Confederation, but as there were apprehensions that some of 'them might refuse to abandon the Confederation and adopt the new scheme of government, the seventh article provided that if nine States should adopt it, it should be a "Constitution between the States so ratifying the same," the other four States to be left to take care of themselves as they could.2

At the ensuing sessions of the Legislatures, all of them except that of Rhode Island called Conventions to consider the ratification of the new Constitution. Delaware ratified it on the 7th of the following December, and New Hampshire on the 21st of June, 1788. These were the first and the last of the necessary nine, but five days after the latter date Virginia and New York acceded to the new Union.3 Thereupon steps were taken to hold the elections required by the new order of things, and to inaugurate the Government.

North

Carolina's Convention refused

to carry the State into the Union, and she and Rhode Island remained

out of the Union until sixteen and twenty-two months, respectively,

after the ratifications of the necessary nine, their objections having

been in the meantime removed by such amendments to the Constitution as

were thought to be effective barriers to usurpation.4

[These states were actually threatened with embargo.]

In the public mind and in the State Conventions there were many objections to the proposed Constitution founded on the total darkness which had enveloped the proceedings of the Convention which framed it.

Some of the erroneous interpretations which the publication of the "secret proceedings" disposed of, have at different times been palmed off on the people as authoritative expositions. For example, Patrick Henry stoutly opposed the ratification by Virginia, and demanded to know why it said "We, the people" instead of "We, the States." "If," he continued, "the States be not the agents of this Compact, it must be one great, consolidated, National Government of all the States." But the "secret proceedings," afterwards published, showed that the final draft of the Constitution, submitted to the Convention August 6 by the Committee of Five, began with "We, the people of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island," etc., naming all the thirteen States; and that the names of the States were stricken out for the reason that it was not known whether all the States would ratify it, or how many more States would ultimately be admitted into the Union. But this "We, the people" does duty to-day in bolstering up our "great consolidated, National Government."

Mr. Greeley quotes Henry with much satisfaction; but, like Josh Billings's lazy man hunting for a job of work, he read Elliott's Debates "with a great deal of caution." If he had turned to page 94 of Volume III - from which volume, pages 22 and 24, he had quoted Henry's words - he would have found this answer from Madison: "I can say, notwithstanding what the honorable gentleman has alleged.... Who are parties to it? The people - but not the people as composing one great body; but the people as composing thirteen sovereignties. Were it, as the gentleman asserts, a consolidated government, the assent of a majority of the people would be sufficient for its establishment; and as a majority have adopted it already, the remaining States would be bound by the act of the majority, even if they unanimously reprobated it," etc.

But this is anticipating.

The importance of the subject requires that the reader shall have as a preface to the main discussion a brief history of the relations of the States to each other previous to the formation of the "more perfect Union."

Exposed to dangers from Indians and other enemies, the British Colonies in North America very early recognized the duty as well as the necessity of defending each other; and (omitting two unimportant confederacies) apprehending in 1754 that the war between England and France would involve the British and French Colonies in North America, the four New England Colonies, New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland, sent Commissioners to a Congress at Albany, N. Y., for the purpose of negotiating a treaty of peace with the Indians who, it was feared, might become allies of the French. This was done; and then the Congress formulated a scheme of a general government of all the British Colonies. But the scheme was rejected by the King of England and by every one of the Colonies.

After the close

of the war (1764)

England revived, amended, and instituted measures to enforce her old

law of 1733 (levying duties on sugar and molasses) which New England

shippers and traders had evaded, and which had never been strictly

enforced, her avowed excuse being that these Colonies ought to

contribute to the payment of her large war debt contracted in part for

the defense of the Colonies against the French and their Indian allies.5

This created considerable excitement in Boston,6 which was the largest town in all the Colonies, and imported more molasses than all the other seaport towns on the continent; but outside of Massachusetts there was no manifestation of serious discontent.

But when the Stamp Act was passed in 1765, imposing taxes which everybody could see and feel, there was a storm of opposition in all the Colonies, particularly in the towns on the seacoast.

Thereupon, at the urgent request of Massachusetts, delegates from all the Colonies except Canada, New Hampshire, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia met in a Congress in New York in October, 1765. This Congress of nine Colonies adopted a declaration of rights, and sent an address to the King and a petition to the Parliament, asserting the right of all the Colonies to be "exempted from all taxes not imposed by their consent" - a very remarkable doctrine in the light of subsequent events.7

Societies were formed here and there to arouse the people of the several Colonies against the claims of the British Government, and the merchants of Boston, New York and Philadelphia agreed with each other not to buy any more goods from Great Britain until the Stamp Act should be repealed.8

The Stamp Act was repealed the next year; but an act was passed imposing taxes on glass, paper, painters' colors, and tea, on their importation into the Colonies. It was approved by George III in June, 1767.

In February, 1768, the Colonial Legislature of Massachusetts sent a circular to the legislative bodies in the other Colonies, asking their cooperation in efforts to obtain a redress of grievances.9 This circular was very offensive to the British Government, and a demand for its rescission was sent over; but Massachusetts refused to rescind, and even reaffirmed its doctrines in stronger language. Then ensued a contest between that Colony and the mother country, the latter sending over a body of troops to suppress the "rebels." The excitement increased; the presence of the British troops in Boston added to the causes of irritation, and both sides seemed willing to invite an open rupture. On the 5th of March, 1770, a quarrel arose between a military guard and a number of the townsfolk who, under the lead of Crispus Attucks, a negro, surrounded the guard and attacked it "with clubs, sticks and snow-balls covering stones." Being dared to fire by the mob, six of the soldiers discharged their muskets, which killed three of the crowd and wounded five others. The Captain and eight men were brought to trial for murder, John Adams and Josiah Quincy defending them. All were acquitted except two, who were convicted of manslaughter. These praying the benefit of clergy were branded with hot irons, and dismissed.10

But this "Boston massacre" served the purpose of still further inflaming the passions of the people against the mother country.11

About the same time a conciliatory measure was passed by the Parliament repealing all the taxes imposed by the Act of 1767 except that on tea. But this was not conciliatory enough, and an act was passed in 1773 permitting the East India Company to carry their tea into the Colonies and undersell the smugglers of Dutch tea.12 All export taxes and other restrictions were removed except a duty of three pence per pound to be paid in the port of entry, which was considerably below the taxes paid in the mother country. It was hoped that this measure would pacify the Colonies; but it was objected to not only in the Colonies, but by the tea merchants of England, who united with the smugglers in appealing to the patriotism Of the Colonists to refuse to buy the cheap teas. The importation of this tea was resisted in the principal importing cities, notably in Boston, where the smugglers organized a band of "Mohawk Indians" and dumped into the sea about $100,000 worth of tea.13

In consequence of these and other violent proceedings the Parliament passed, in succession, during the next seven weeks, beginning with March 23, four acts, which were commented on as follows by Alexander Elmsly, one of North Carolina's agents in London, in a letter dated May 17, 1774: "By the first (Boston Port Bill)14 the harbor of Boston is shut up till a compensation is made to their Indian Company for their tea, and till the inhabitants discover an inclination to submit to the revenue laws, after which the King, by and with the advice of the Privy Council, is empowered to suspend the effect of the act....

"The next act is for taking away the charter of the Massachusetts Bay; hereafter the Council are to be appointed by the King, as in the Southern Provinces, and in certain cases the Governor is to act without their consent and concurrence. The town meetings, except for the purpose of elections, are declared unlawful, and some other new regulations established:

"The third act enables the Governors, in case of an indictment preferred against any officer of the Crown, either civil or military, for anything by him done in the execution of his office, to suspend the proceedings against him in America, and to send him home for trial in England. This law. I am told, the officers of the army insisted on for fear of being prosecuted by the civil power, either as principals or accessories to the death of any person killed in the field of battle, in case things should come to that extremity.

"The fourth and last law respects quartering the soldiery. I have not seen it, but suppose it is calculated to obviate in future the construction put upon the old one, by the people of Boston, in their town meeting, viz, that Castle William, situated three miles out of town, should be taken to be barracks in the town, and of course excluded the pretensions of the army to quarters in the town, even though the purpose of sending soldiers should be merely on account of the commotions and disturbances in the town."15

When the people of Boston heard of the passage of the first of these acts they were greatly excited; and a meeting was called "to consider this new and unexampled aggression. It was there voted to make application to the other Colonies to refuse all importations from Great Britain, and withhold all commercial intercourse, as the most probable and effectual mode to procure the repeal of this oppressive law. One of the citizens was despatched to New York and Philadelphia, for the purpose of ascertaining the views of the people of those places and iu the Colonies farther South.16 A committee, comprising Samuel Adams, Dr. Warren, with John Adams and others of the same high character, was appointed to consider what farther measures ought to be adopted.

"The Governor obliged the General Court (Legislature) to meet at Salem, instead of Boston, where they proceeded, after a very civil address to him, to ask for a day of general fast and prayer. This his Excellency refused. But, although he would not let them pray, he could not prevent them from adopting a most important measure, namely, that of choosing five delegates to a General and Continental Congress; and of giving information thereof to all the other Colonies, with the request that they would appoint deputies for the same purpose." (See Life of John Adams in Lives of the Signers, etc.)

Much sympathy for Massachusetts was manifested in other Colonies. The Assembly of Virginia appointed the 1st of June (1774)17 as a day of "fasting, humiliation, and prayer." "The Royal Governor immediately dissolved the House of Burgesses; whereupon the members resolved themselves into, a Committee," passed resolutions declaring in substance that "the cause of Boston was the cause of all," and took steps to induce the other Colonies to appoint delegates to the General Congress, which had been proposed by the Bostonians.

North Carolina's first Legislative Assembly elected by the people, which met in Newbern August 25, 1774, while declaring the allegiance of the people to the House of Hanover, denounced the Boston Port Bill as unconstitutional; approved the plan for a General Congress of the Colonies in September, and appointed delegates to the same.18

On the 5th of September, 1774, delegates from all the Colonies except Canada and Georgia met in Philadelphia and organized the first Continental Congress, assuming the style of the Twelve United Colonies.

The first act of this body was to recognize the equality of the Colonies by agreeing that in determining any question each Colony should have one vote: and this equality was preserved by subsequent Congresses, by the States under the Articles of Confederation, and, in the Senate, under the Constitution. Without it cooperation and Union would have been impossible.

Being little more than an advisory body, each delegation having no power to do more than it had been instructed to do by its own Colony, it appointed committees to take into consideration the rights and grievances of the Colonies, asserting by numerous declaratory resolutions what were deemed to be the inalienable rights of English freemen; pointed out to the people of the Colonies the dangers which threatened those rights; besought them to renounce commerce with Great Britain as the most effective means of averting those dangers: and advised all the Colonies to send delegates to a General Congress, to be held in the same place in May of next year.

In the meantime the British Government, mistaking the temper of the people of the other Colonies, and not realizing that "the cause of Boston was the cause of all," proceeded to other acts of Folly. An act of Parliament, which received the King's assent March 1, restrained "the trade and commerce of the Provinces of Massachusetts Bay and New Hampshire, and the Colonies of Connecticut and Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in North America, to Great Britain, Ireland and the British Islands in the West Indies," and prohibited "such Provinces and Colonies from carrying on any fishery on the banks of Newfoundland or other places therein mentioned, under certain conditions and limitations."

This act not only affected the business of the fishermen, but it diminished the food supplies of the poor of Boston, and would have produced great distress in the town if contributions had not poured into it from other Colonies.

There was, therefore, a new incentive to comply with the recommendation of the Congress of the preceding year; and accordingly delegates were appointed, and met in Philadelphia in May, 1775, all being represented except Canada and Georgia,19 as before, although delegates from the latter arrived in July.

The powers of the delegates were not well defined; but reconciliation with England was to be kept steadily in view. On the day - April 5, 1775 - when Messrs. Hooper, Hewes and Caswell were reappointed as North Carolina's delegates, they said in an address to the Provincial Convention: "One motive in this important measure, viz, a sacred regard for the rights and privileges of British America, and an earnest wish to bring about a reconciliation with our parent State, upon terms Constitutional and honorable to both, have hitherto actuated us." Previous to the meeting of this Congress open hostilities had broken out between Massachusetts and Great Britain (which probably stimulated Georgia to active cooperation), the battle of Lexington having been fought a few weeks before. The news of this battle spread rapidly and created intense excitement. Volunteers from the adjoining Colony of Connecticut and from what afterwards became Vermont, under the leadership of Col. Ethan Allen, seized upon the military posts of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, both on the west side of Lake Champlain, and White Hall at its southern extremity. The capture of Ticonderoga was effected on the 10th of May, the day on which the Congress met.

New England had now passed the Rubicon; a step had been taken which imposed on the other Colonies the necessity of choosing whether they would stand aloof and permit her to be crushed by Great Britain, or go to her relief with men and money. They chose the latter; the "cause of Boston had become in a new and fearful sense" the cause of all. "Their delegates in the Congress proclaimed a declaration of the reasons for the appeal to arms, passed a resolution to raise 20,000 troops, each Colony to furnish its quota on an agreed equitable basis; appointed, on the nomination of Massachusetts, George Washington, of Virginia, to be Commander-in-Chief of all the Colonial forces;20 and made other preparations for defending the rights of the Colonies against what they considered unwarranted aggressions, actual or threatened, on their chartered rights. "We have not raised armies," they declared, "with ambitious designs of separating from Great Britain and establishing independent States. We fight not for glory or conquest.... We shall lay them (arms) down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the aggressors, and all danger of their being renewed shall be removed, and not before."21

But revolutions never go backward; and, in the light of history, this declaration of the representatives of the Colonies, if sustained by the several Colonies, meant independence or subjugation. It was not so regarded, however, in the Colonies; it was generally expected that the British Ministry would recede from their measures of aggression, as they had so often done before. Accordingly the people in many of the Colonies were attempting, for months after General Washington took command at Boston, to bring about accommodations with the Royal Governors. In New Jersey the expectation of a reconciliation was not abandoned even as late as July 2, 1776, when her new frame of government was adopted.22

This Congress remained in session several months, and the delegates, obeying instructions from their several Colonies, declared, July 4, 1776 (though New York's assent was not obtained till July 9), that these Colonies renounced all allegiance to the British sovereign; and "that as free and independent States, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent States may of right do."23

About the same time a plan of union was being drafted by a committee which had been appointed early in June. The result of their labors was the Articles of Confederation, which were submitted November 15, 1777, to the several State Legislatures, with a request for instructions to their several delegations to approve and sign them.

They proposed in the preamble to establish "a Confederation and perpetual union between the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia." They were also translated into the French language and sent with an address to the people of the British Provinces north of these States, the eleventh article providing that "Canada acceding to this Confederation and joining in the measures of the United States, shall be admitted into, and entitled to, all the advantages of this Union," and that other Colonies might be admitted by the assent of nine States.

On the 9th of July, 1778, the Articles were signed by the delegates from the New England States, New York, Virginia and South Carolina, New York's approval being on the condition that all the other States would approve. The delegates from New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland refused to sign because their States had not so instructed them, while North Carolina and Georgia were not represented. In the course of ten months, however, all the States except Maryland acceded to the Confederation. She stood aloof until March 1, 1781, the last year of active hostilities. Practically, therefore, the war was waged under the Continental Congress, which was little more than an advisory body, all really effective political power being in the several States. After the war was ended the Articles of Confederation, designed principally as the Constitution of a military government, were found unsuited to the new situation. The excitement of the war period and the necessity for extra exertion, which could be relied on as inducements for each State to furnish its quota of requisitions to the general treasury, had now passed away; and the Legislatures of the several States were loath to burden their impoverished constituents with even the taxes necessary to discharge their own obligations, contracted in each State for the maintenance of its own military organization and the defense of its own soil. Hence there was inadequate provision for the debts and obligations of the Continental Congress and "the United States in Congress assembled."

This situation induced some of the ablest men in the States to advocate amending the Articles of Confederation so that the "United States in Congress assembled" could lay and collect taxes; and in a short time commercial jealousies of particular States, threatening the peace of the Union, indicated the necessity of other amendments. At last, after four years of uncertainty and discontent - counting from the definitive treaty of peace - a Convention was called, framed a new Constitution, and asked the States to ratify it, as we have seen.

This general survey of the relations, of the States prepares us for a somewhat critical inquiry into the structure of the Union, which, we will postpone to the next chapter, wherein we shall study the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution.

BRITISH TAXATION AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE COLONIES OF NORTH AMERICA.

"Taxation without representation" has always been held to have been the cause of the Revolutionary war; but familiar as we are with the difficulty of bringing the masses of the people to a realization of the heavy tax burden imposed on them by the Federal Government, it is not easy to understand how the peoples of all the Colonies could have been induced to unite in measures of opposition to British taxation. To-day the average man who complains if his direct tax to his State, county or town amounts to $25, will in the course of a year pay to his merchant $150 for his purchases, $75 of it going to the Federal treasury, if the goods are foreign, or into the pocket of the manufacturer, if they are domestic; and he will do this without a murmur, because the tax is concealed from him, being levied, as Turgot said, so as to pluck the goose without making it cry.

The historians who have persistently asserted that Great Britain never "attempted directly or indirectly to derive a dollar of revenue" from these Colonies, have never satisfactorily accounted for the existence of Custom Houses at all the seaports. They tell us that the Custom House was moved from Boston to Salem; but the reader is left in the dark as to the duties of the officers. The truth seims to be that taxes were collected on certain imports, to which the importer raised no objection, because he reimbursed himself when he sold the articles to his customers, who, as now, did not see the tax "wrapped up" in the price. Hence it was easy to convince the great majority of the people, as it is now, that they were not taxed by tariff acts.

But import taxes were not all. In all the Royal Colonies there was an annual land tax called "quit rents," collected by the King's officers and turned over to the Royal Treasury. In 1729, when George II bought seven shares of North Carolina from the Lords Proprietors, he paid 5,000 pounds for the "quit rents" then in arrears. The custom was to sell land for a nominal sum-50 shillings per 100 acres and stipulate for this annual rent, which was usually four shillings per 100 acres, or nearly one cent per acre.

This was quite a heavy tax; it would amount to-day to about a quarter of a million of dollars in North Carolina. But there was no outcry against it.

The New England Colonies sent Col. Ethan Allen twice into Canada, in the autumn of 1775, to observe the disposition of the people and enlist their cooperation, with apparently favorable results. In a letter from John Penn, one of North Carolina's delegates in the Continental Congress, to Thomas Person, dated February 12, 1776, he said: "The Canadians in general are on our side." - North Carolina Colonial Records, X, 448.

And about the time Penn wrote this letter the Congress sent Dr. Franklin, Samuel Chase and Charles Carroll on a mission to Canada; and in April invited Father John Carroll (Charles's cousin) to go with them. The latter was selected "because of his... religious standing among his brethren of the Catholic faith, and because of his knowledge of the French language, and of his influence with the Canadians."

We may never know the reasons why this mission failed. Possibly religious prejudices stood in the way of their cooperating with the Puritans of New England; possibly the defeat and expulsion from Canada of the expeditions under Arnold and Montgomery in December, 1775, had its influence; and possibly Hildreth gives the true reason (Vol. III, p. 33) in the following paragraph:

"A fifth act of Parliament, passed April 15, 4774, known as the Quebec Act, designed to prevent that newly acquired Province from joining with the other Colonies, restored in civil matters the old French law - the custom of Paris - and guaranteed to the Catholic Church the possession of its ample property, amounting to a fourth part or more of the old French grants, with the full freedom of worship," etc.

The absence of Georgia's delegates may be accounted for by remembering that she was farthest removed from the storm centre, and, therefore, less easily brought under its influence. Alden's Cyclopoedia (Art. Massachusetts) says: "From the beginning of her great struggle against oppression, Massachusetts had the active sympathy of her sister Colonies, who had far less cause for complaint than she." But there is danger of confounding sympathy for the suffering poor with sympathy for the "rebels"; the latter was a plant of slow growth in many of the Colonies.

As to Georgia's grounds for

complaint against England, this Cyclopcedia (Art. Georgia) says: "It

was acknowledged at the time, and the claim has since been

substantiated beyond question, that the people of Georgia had no cause

for personal or Colonial dissatisfaction with England during the

exciting days that preceded the Revolution. The relations between the

Colony and the home government had been wholly amicable, and none of

the acts of oppression of which the New England Colonies particularly

complained had been enforced against Georgia."

footnotes:

1. Mr. Greeley, in his efforts to find excuses for the conduct of his political associates, asserts that powers were granted of which the people were kept in ignorance. In his American Conflict, Volume II, page 232, he says: "The Constitution was framed in General Convention, and carried in the several State Conventions, by the aid of adroit and politic evasions and reserves on the part of its framers and champions. * * * Hence the reticence, if not ambiguity, of the text with regard to what has recently been termed coercion, or the right of the Federal Government to subdue by arms the forcible resistance of a State, or of several States, to its legitimate authority. So with regard to slavery as well," etc.

From which view of the Constitution, if it were correct, two deductions seem unavoidable:

1. The Revolutionary war was a mistake; and

2. The ratification of the Constitution, secured by fraud, is not binding on any State.

[Online editor's note: There is considerable evidence that

Greeley's assessment of the Consitutional Convention was correct. This

does not mean the Revolutionary War was a mistake, as the Constitution

was not adopted until the war was over. It does give credence that the

Constitution was secured by fraud.]

2. The reader should note that "between" is used here for the obvious reason that the Constitution was to be of the nature of a compact between (betwain or by two) two parties, namely, each State as one and its co-States as the other. And the consolidationist may select either horn of the dilemma: If it was intended to establish a new Union, here is recognized the right of nine States to withdraw from the old one; if it was intended simply to amend the old Union, the right of four States to withdraw from it is recognized.

3. There was formidable and in some instances violent opposition to the ratification of the Constitution. In the Massachusetts Convention, composed of 355 members, after a three weeks debate, it was carried by 19 majority. But in Pennsylvania the proceedings were even more interesting, as we gather from the protest of the opponents of the Constitution, as given on page 29, Volume I, second series, Hildreth's History: "The resolution introduced in the Assembly of Pennsylvania for holding that Convention (to consider the new Constitution) had allowed a period of only 10 days within which to elect the members of it; and the minority in the Assembly had been able to find no other means of preventing this precipitation, except by absenting themselves, and so depriving the House of a quorum. But the majority were not to be so thwarted; and some of these absentees... had been seized by a mob, forcibly dragged to the House, and there held in their seats, while the quorum so formed gave a formal sanction to the resolution. It was further alleged (by the protest) that of 70.000 legal voters, only 13,000 had actually voted for members of the Ratifying Convention; and that the majority who voted for ratification had been elected by only 6,800 votes."

4. North Carolina's

objections to the Constitution may be seen in the

following resolution passed on the 1st of August, 1788, after that

instrument had been defeated by a vote of 184 to 84:

"Resolved, That a declaration of rights, asserting and securing from encroachments the great principles of civil and religious liberty, and the unalienable rights of the people, together with amendments to the most ambiguous and exceptionable parts of the said Constitution of government, ought to be laid before Congress and the Convention of the States that shall or may be called for the purpose of amending the said Constitution, for their consideration, previous to the ratification of the Constitution aforesaid on the part of the State of North Carolina." - Elliot's Debates, I, 331.

5. "The following extract from Smith's Wealth of Nations (Vol. II. p. 66), the first edition of which was published in the winter of 1775-'76, will give us light on this as well as some other matters: "The expense of the civil establishment of Massachusetts Bay used to be about eighteen thousand pounds per year; that of New Hampshire and Rhode Island 3,500 pounds each; that of Nee Jersey 1,200 pounds; that of Virginia and South Carolina 8,000 pounds each. The civil establishments of Nova Scotia and Georgia are partly supported by an annual grant of Parliament. But Novia Scotia pays, besides, about seven thousand pounds a year towards the public expenses of the Colony; and Georgia about two thousand five hundred pounds.... The most important part of the expense of government, indeed, that of defense and protection, has constantly fallen upon the mother country."

6. Of James Otis, the most active of Massachusetts patriots in denouncing and agitating against this law, Alden's Cyclopedia says: "His opposition to the Royal Government developed 1761, and was claimed by some to have been greatly intensified, if not wholly caused, by the refusal of Governor Bernard to give his father (James Otis, Sr.), the position of Chief-Justice, for which he had applied on the death of Sewall."

7. At

least five of the States were taxed from 1824

to 1833 (as will be

shown in another chapter), not only without their consent, but in spite

of their protests; and eleven of them. were taxed for seven years (from

and including 1865) far more heavily than Great Britain ever proposed

to tax them, not only without their consent, but without their being

permitted to send Representatives to either House of the Congress; and

among the burdens imposed on them was a Stamp Act."

9. John Hancock, one of the wealthiest merchants and ship-owners in Boston, was one of those who evaded these taxes. His vessel, Liberty, was seized by the Royal Commissioners of Customs in 1768 for violations of the law; and the seizure was followed by a riot. The officers were beaten with clubs, the boat of the Collector was burnt in triumph, and the houses of some of the most conspicuous adherents of the Government were razed to the ground. From these events Hancock gained great popularity, and easily came to the front of Massachusetts patriots.

10. When Massachusetts invaders fired on and killed some of the people of Baltimore, April 19, 1861, they were not branded or even tried.

11. It

would be grossly unjust to the Irishmen and

the children of

Irishmen who dwelt in the Colonies, particularly those of the South, if

we failed to recognize the part they played in uniting the Southern

Colonies with New England, and in waging the war. It would be a

pleasant task to search the records and gather up a list of the

advocates of independence, at the head of which would stand the names

of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Patrick Henry, Hugh Williamson, James

Moore, Thomas Lynch, Edward Rutledge, and others; but we must forego

that pleasure, and be satisfied with what may be considered competent

evidence of Irish devotion to the cause of independence. Joseph

Galloway, Speaker of the Pennsylvania

House of Assembly, at the beginning of the troubles, refused to join in

measures of resistance, and in October, 1778, he left the States and

went to England. There he was examined by a Committee of the House of

Commons, and, when asked who composed the armies of the Continental

establishment, he answered: "The names and places of their nativity

being taken down, I can answer the question with precision. There were

scarcely one-fourth natives of America - about one-half Irish; the

other

fourth were English and Scotch." - Dillon's Historical Evidence on the

Origin and Nature of the Government of the U. S. (New York, 1871), p.

56. (See also North Carolina Colonial Records, IX, 1,246.)

12. Nine-tenths of all the tea they imported was smuggled from Holland. - See Montgomery's Amer. Hist. (Boston, 1894), p. 154.

13. In a letter to the Earl of Dartmouth, dated New York, November 4, 1774, Josiah Martin, the Royal Governor of North Carolina, advises the repeal of the tea tax, and gives this among other reasons: "It will disappoint the views of the smugglers of Dutch tea who have made monstrous advantages of the opposition they have industriously excited and fomented on this subject, professing to aim by these means at the repeal of the Tax Act, which they certainly intended to produce a contrary effect, deprecating in their hearts that course above all things that must inevitably destroy their monopoly of that commodity and all its concomitant bene-fits." - North Carolina Colonial Records, IX, 1,085-86.

15. North Carolina Colonial Records, IX, 1,000.

16. It

seems that Massachusetts had agents travelling through

the Southern

Colonies before this. From the Memoirs of Josiah Quincy, Jr., we learn

that in March and April, 1773, he visited William Hill, Esq. (a native

of Boston), a merchant of Brunswick, N. C., whom he found "warmly

attached to the cause of American freedom"; breakfasted with Colonel

Dry, the Collector of Customs at Brunswick, whom he found to be a

"friend to the Regulators"; dined in Wilmington "with Dr. Cobham with a

select party"; dined again with Dr. Cobham "in company with Harnett,

Hooper, Burgwin, Dr. Tucker," etc.; "dined with about twenty at Mr.

William Hooper's"; spent the night with Mr. Cornelius Harnett - "the

Samuel Adams of North Carolina (except in point of fortune)" - "Robert

Howe, Esq.," being one of "the social triumvirate"; went to New

Bern, Bath and Edenton; breakfasted with Colonel Buncombe;

and spent two days crossing Albemarle Sound "in company with the most

celebrated lawyers of Edenton." - (See North Carolina Colonial Records,

Vol. IX, pp. 610 and 611.)

17. The day when the Boston Port Bill was to go into effect.

18. Sympathy for Boston was not confined to resolutions; it was manifested in a more practical way. Provisions and other necessaries were sent to that city from all the seaboard towns of the Southern Colonies, contributed in some instances by counties and settlements far removed from the coast. - (See North Carolina Colonial Records, Vol. IX, pp. 1,017, 1,018, 1,033, 1,081, 1,116, etc.).

And this sympathy inspired the Bostonians to consult the Continental Congress about the propriety of burning the town in "order to distress the military," taking care in the meantime to estimate "the value of the houses, etc., in order to raise a general contribution for the loss at some future time." - (See North Carolina Colonial Records, Vol. IX, p. 1,082).

20. This was an effective piece of diplomacy. "The delegates from New England were particularly pleased with his election, as it would tend to unite the Southern Colonies cordially in the war." - Am Mil. Biog., 325. But it was very offensive to the New England officers who had hitherto commanded in their military operations. Some of them refused to serve under "Continental officers," notably John Stark, Seth Warner, Artemas Ward, and Seth Pomeroy.

21. On the 26th of April, 1775 - a week after the battle of Lexington - the Legislature of Massachusetts, in session at Watertown, issued an "Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain," which contained the following passage: "They" (the British Ministry) "have not yet detached us from our Royal Sovereign; we profess to be his loyal and dutiful subjects." - Dillon's Hist. Evidence, page 54.

22. Since Massachusetts was the first Colony to resist Great Britain, it would be natural to suppose that she was first to propose independence; but she was behind the Southern Colonies, North Carolina taking the lead on April 12.

Bancroft obscures this disagreeable truth in the following passage in Volume VIII, page 449: "Comprehensive instructions reaching the question of independence without explicitly using the word, had been given by Massachusetts in January."

23. Samuel Johnston, President of the North Carolina Assembly, in a letter to Messrs. Hooper, Hewes and Penn, dated April 13, 173,6 said: "The North Carolina Congress have likewise taken under consideration that part of your letter requiring their instructions with respect to entering into foreign alliances, and were unanimous in their concurrence with the enclosed resolve, confiding entirely in your discretion with regard to the exercise of the power with which you are invested." - North Carolina Colonial Records, X, 495.

Comments. We are interested in comments that generate more light than heat. Please avoid grandstanding:

Saving Communities

420 29th St.

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263