Origin of Civilization

Epigraph to Book IThough but an atom midst immensity, - Bowring's translation of Dershavin This book was transcribed into shtml by Dan Sullivan, and was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works. |

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

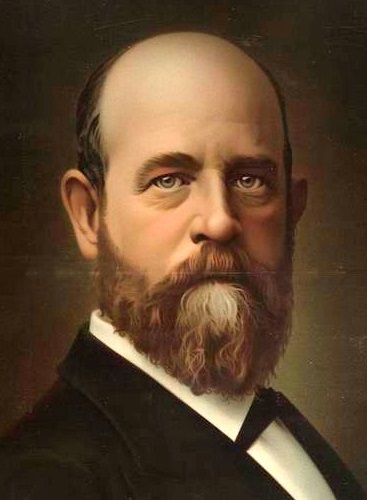

Henry George

|

Reason the power of tracing causal relations - Analysis and synthesis - Likeness and unlikeness between man and other animals - Powers that the apprehension of causal relations gives - Moral connotations of civilization - But begins with and increases through exchange - Civilization relative, and exists in the spiritual.

Man is an animal; but an animal plus

something more - the

divine spark differentiating him from all other animals, which enables

him to become a maker, and which we call reason. To style it a divine

spark is to use a fit figure of speech, for it seems analogous to, if

not indeed a lower form of, the power to which we must attribute the

origin of the world; and like light and heat radiates and enkindles.

The essential quality of reason seems to

lie in the power of tracing

the relationship of cause and effect. This power, in one of its

aspects, that which proceeds from effect to cause, thus, as it were,

taking things apart, so as to see how they have been put together, we

call analysis. In another of its aspects, that which proceeds from

cause to effect, thus, as it were, putting things together, so as to

see in what they result, we call synthesis. In both of these aspects,

reason, I think, involves the power of picturing things in the mind,

and thus making what we may call mental experiments.

Whoever will take the trouble (and if he

has the time, he will find in

it pleasure) to get on friendly and intimate terms with a dog, a cat, a

horse, or a pig, or, still better, - since these animals, though they

have four limbs like ours, lack hands, - with an intelligent monkey,

will find many things in which our "poor relations" resemble us, or

perhaps rather, we resemble them.

To such a man these animals will exhibit

traces at least of all human

feelings - love and hate, hope and fear, pride and shame, desire and

remorse, vanity and curiosity, generosity and cupidity. Even something

of our small vices and acquired tastes they may show. Goats that chew

tobacco and like their dram are known on shipboard, and dogs that enjoy

carriage-rides and like to run to fires, on land. "Bummer" and his

client "Lazarus" were as well known as any two-legged San Franciscan

some thirty-five or forty years ago, and until their skins had been

affectionately stuffed, they were "deadheads" at free lunches, in

public conveyances and at public functions. I bought in Calcutta, when

a boy, a monkey which all the long way home would pillow her little

head on mine as I slept, and keep off my face the cockroaches that

infested the old Indiaman by catching them with her hands and cramming

them into her maw. When I got her home, she was so jealous of a little

brother that I had to part with her to a lady who had no children. And

my own children had in New York a little monkey, sent them from

Paraguay, that so endeared herself to us all that when she died from

over - indulgence in needle - points and pinheads it seemed like losing

a member of the family. She knew my step before I reached the door on

coming home, and when it opened would spring to meet me with chattering

caresses, the more prolonged the longer I had been away. She leaped

from the shoulder of one to that of another at table; nicely

discriminating between those who had been good to her and those who had

offended her. She had all the curiosity attributed to her sex in man,

and a vanity most amusing. She would strive to attract the attention of

visitors, and evince jealousy if a child called off their notice. At

the time for school-children to pass by, she would perch before a front

window and cut monkey shines for their amusement, chattering with

delight at their laughter and applause as she sprang from curtain to

curtain and showed the convenience of a tail that one may swing by.

How much "human nature" there is in

animals, whoever treats them kindly

knows. We usually become most intimate with dogs. And who that has been

really intimate with a generous dog has not sympathized with the

children's wish to have him decently buried and a prayer said over him?

Or who, when he saw at last the poor beast's stiffened frame, could,

despite his accustomed philosophy which reserves a future life to man

alone, refrain from a moment's hope that when his own time came to

cross the dark river his faithful friend might greet him on the other

shore? And must we say, Nay? The title by which millions of men prefer

to invoke the sacred name, it is not "the All Mighty," but "the Most

Merciful."

One of the most striking differences

between man and the lower animals

is that which distinguishes man as the unsatisfied animal. Yet I am not

sure that this is in itself an original difference; an essential

difference of kind. I am, on the contrary, as I come closely to

consider it, inclined rather to think it a result of the endowment of

man with the quality of reason that animals lack, than in itself an

original difference.

For, on the one side, we see that men when placed in conditions that forbid the hope of improvement do become almost if not quite as stolidly content with no greater satisfactions than their fathers could obtain as the mere animals are. And, on the other side, we see that, to some extent at least, the desires of animals increase as opportunities for gratifying them are afforded. Give a horse lump-sugar and he will come to you again to get it, though in his natural state he aspires to nothing beyond the herbage. The pampered lap-dogs whose tails stick out from warm coats on the fashionable city avenues in winter seem to enjoy their clothing, though they could never solve the mystery of how to get it on, let alone how to make it. They come to want the daintiest food served in china on soft carpets, while dogs of the street will fight for the dirtiest bone. I know a cat in the mountains that lives in the woods all the months when leaves are green, but when they turn and die seeks the farmer's hearth. The big white puss that lies curled in the soft chair beside the stove in the hall below, and who will swell and purr with satisfaction when I scratch her head and stroke her back as I pass down, hardly dared sneak into the house a few weeks ago, but now that she finds she is welcome is content with nothing less than the softest couch and the warmest fire. And the shaggy dog that likes so well to sit in a boat and watch the water as it plashes by, makes me wonder sometimes if he would not want a nicely cushioned naphtha launch if he could make out how to get one. Even man is content with the best he can get until he begins to see he can get better. A handsome woman I have met, who puts on for ball or opera an earl's ransom in gems, and must have a cockade in her coachman's hat and bicycle tires on her carriage-wheels, will tell you that once her greatest desire was for a new wash-tub and a better cooking-stove.

The more we come to know the animals the

harder we find it to draw any

clear mental line between them and us, except on one point, as to which

we may see a clear and profound distinction. This, that animals lack

and that men have, is the power of tracing effect to cause, and from

cause assuming effect. Among animals this want is to some extent made

up for by finer sense - perceptions and by the keener intuitions that

we call instinct. But the line that thus divides us from them is

nevertheless wide and deep. Memory, which the animals share with man,

enables them to some extent to do again what they have been first

taught to do; to seek what they have found pleasant, and to avoid what

they have found painful. They certainly have some way of communicating

their impressions and feelings to others of their kind which

constitutes a rudimentary language, while their sharper senses and

keener intuitions serve them in some cases where men would be at fault.

Yet they do not, even in the simplest cases, show the ability to "think

a thing out," and the wiliest and most sagacious of them may be snared

and held by devices the simplest man would with a moment's reflection

"see his way through." *

Is it not in this power of "thinking things

out," of "seeing the way

through" - the power of tracing causal relations - that we find the

essence of what we call reason, the possession of which constitutes the

unmistakable difference, not in degree but in kind, between man and the

brutes, and enables him, though their fellow on the plane of material

existence, to assume mastery and lordship over them all?

Here is the true Promethean spark, the

endowment to which the Hebrew

Scriptures refer when they say that God created man in His own image;

and the means by which we, of all animals, become the only progressive

animal. Here is the germ of civilization.

It is this power of relating effect to

cause and cause to effect which

renders the world intelligible to man; which enables him to understand

the connection of things around him and the bearings of things above

and beyond him; to live not merely in the present, but to pry into the

past and to forecast the future; to distinguish not only what are

presented to him through the senses, but things of which the senses

cannot tell; to recognize as through mists a power from which the world

itself and all that therein is must have proceeded; to know that he

himself shall surely die, but to believe that after that he shall live

again.

It is this power of discovering causal

relations that enables him to

bring forth fire and call out light; to cook food; to make for himself

coats other than the skin with which nature clothes him; to build

better habitations than the trees and caves that nature offers; to

construct tools, to forge weapons; to bury seeds that they may rise

again in more abundant life; to tame and breed animals; to utilize in

his service the forces of nature; to make of water a highway; to sail

against the wind and lift himself by the force that pulls all things

down; and gradually to exchange the poverty and ignorance and darkness

of the savage state for the wealth and knowledge and light that come

from associated effort.

All these advances above the animal plane,

and all that they imply or

suggest, spring at bottom from the power that makes it possible for a

man to tie or untie a square knot, which animals cannot do; that makes

it impossible that he should be caught in a figure-4 trap as rabbits

and birds are caught, or should stand helpless like a bull or a horse

that has wound his tethering-rope around a stake or a tree, not knowing

in which way to go to loose it. This power is that of discerning the

relation between cause and effect.

We measure civilization in various ways,

for it has various aspects or

sides; various lines along which the general advance implied in the

word shows itself - as in knowledge, in power, in wealth, in justice

and kindliness. But it is in this last aspect, I think, that the term

is most commonly used. This we may see if we consider that the opposite

of civilized is savage or barbarous. Now savage and barbarous refer in

common thought and implication not so much to material as to moral

conditions, and are synonyms of ferocious or cruel or merciless or

inhuman. Thus, the aspect of civilization most quickly apprehended in

common thought is that of a keener sense of justice and a kindlier

feeling between man and man. And there is reason for this. While an

increased regard for the rights of others and an increased sympathy

with others is not all there is in civilization, it is an expression of

its moral side. And as the moral relates to the spiritual, this aspect

of civilization is the highest, and does indeed furnish the truest sign

of general advance.

Yet for the line on which the general

advance primarily proceeds, for

the manner in which individual men are integrated into a body economic

or greater man, we must look lower. Let us try to trace the genesis of

civilization.

Gifted alone with the power of relating

cause and effect, man is among

all animals the only producer in the true sense of the term. He is a

producer, even in the savage state; and would endeavor to produce even

in a world where there was no other man. But the same quality of reason

which makes him the producer, also, wherever exchange becomes possible,

makes him the exchanger. And it is along this line of exchanging that

the body economic is evolved and develops, and that all the advances of

civilization are primarily made.

But while production must have begun with

man, and the first human pair

to appear in the world, we may confidently infer, must have begun to

use in the satisfaction of their wants a power essentially different in

kind from that used by animals, they could not begin to use the higher

forms of that power until their numbers had increased. With this

increase of numbers the cooperation of efforts in the satisfaction of

desires would begin. Aided at first by the natural affections, it would

be carried beyond the point where these suffice to begin or to continue

cooperation by that quality of reason which enables the man to see what

the animal cannot, that by parting with what is less desired in

exchange for what is more desired, a net increase in satisfaction is

obtained.

Thus, by virtue of the same power of

discerning causal relations which

leads the primitive man to construct tools and weapons, the individual

desires of men, seeking satisfaction through exchange with their

fellows, would operate, like the microscopic hooks which are said to

give its felting quality to wool, to unite individuals in a mutual

cooperation that would weld them together as interdependent members of

an organism, larger, wider and stronger than the individual man - the

earlier and Greater Leviathan that I have called the body economic.

With the beginning of exchange or trade

among men this body economic

begins to form, and in its beginning civilization begins. The animals

do not develop civilization, because they do not trade. The simulacra

of civilization which we observe among some of them, such as ants and

bees, proceed from a lower plane than that of reason - from instinct.

While such organization is more perfect in its beginnings, for instinct

needs not to learn from experience, it lacks all power of advance.

Reason may stumble and fall, but it involves possibilities of what seem

like infinite progression.

As trade begins in different places and

proceeds from different

centers, sending out the network of exchange which relates men to each

other through their needs and desires, different bodies economic begin

to form and to grow in different places, each with distinguishing

characteristics which, like the characteristics of the individual face

and voice, are so fine as only to be appreciated relatively, and then

are better recognized than expressed. These various civilizations, as

they meet on their margins, sometimes overlap, sometimes absorb, and

sometimes overthrow one another, according to a vitality dependent on

their mass and degree, and to the manner in which their juxtaposition

takes place.

We are accustomed to speak of certain

peoples as uncivilized, and of

certain other peoples as civilized or fully civilized, but in truth

such use of terms is merely relative. To find an utterly uncivilized

people we must find a people among whom there is no exchange or trade.

Such a people does not exist, and, so far as our knowledge goes, never

did. To find a fully civilized people we must find a people among whom

exchange or trade is absolutely free, and has reached the fullest

development to which human desires can carry it. There is, as yet,

unfortunately, no such people.

To consider the history of civilization,

with its slow beginnings, its

long periods of quiescence, its sudden flashes forward, its breaks and

retrogressions, would carry me further than I can here attempt.

Something of that the reader may find in the last grand division of

Progress and Poverty, Book X, entitled, "The Law of Human Progress."

What I wish to point out here is in what civilization essentially and

primarily consists. But this is to be remembered: Neither what we speak

of as different civilizations nor yet what we call civilization in the

abstract or general has existence in the material or is directly

related to rivers and mountains, or divisions of the earth's surface.

Its existence is in the mental or spiritual.

* I do not of course include the animals of fairy tale, nor the superordinary dogs that Herbert Spencer's correspondents write to him about. See Herbert Spencer's Justice, Appendix D, or my A Perplexed Philosopher, p. 285.

Comments:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263