Growth of Knowledge

Epigraph to Book IThough but an atom midst immensity, -- Bowring's translation of Dershavin Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works. |

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

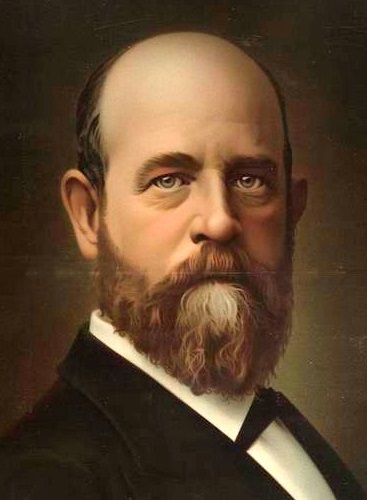

Henry George

|

Civilization implies greater knowledge -- This gain comes from cooperation -- The incommunicable knowing called skill -- The communicable knowing usually called knowledge -- The relation of systematized knowledge to the means of storing knowledge, to skill and to the economic body -- Illustration from astronomy.

In contrasting man in the civilized state with man in his primitive state I have dwelt most on the gain in the power of gratifying material desires, because such gains are most obvious. Yet as thought precedes action, the essential gain which these indicate must be in knowledge. That the ocean steamship takes the place of the hollow log, the great modern building of the rude hut, shows a larger knowledge utilized in such constructions.

To consider the nature of this gain in knowledge is to see that it is not due to improvement in the individual power of knowing, but to the larger and wider cooperation of individual powers; to the growth of that body of knowledge which is a part, or rather, perhaps, an aspect of the social integration I have called the body economic. If we could separate the individuals whose knowledge, correlated and combined, is expressed in the ocean steamship or great modern building, it is doubtful if their separate knowledge would suffice for more than the constructions and tools of the savage.

The knowledge that comes closest to the individual is what we call skill, which consists in knowing how to govern the organs directly responsive to the conscious will, so as to bring about desired results. Whoever, in mature years, has learned to do some new thing, as for instance to ride a bicycle, knows how slowly and painfully such knowledge is acquired. At first each leg and foot, each arm and hand, to say nothing of the muscles of the chest and neck, seems to need separate direction, which the conscious mind cannot give so quickly and in such order as to prevent the learner from falling off or running into what he would avoid. But as the effort is continued, the knowledge of how to direct these muscles passes from the domain of the conscious to that of the subconscious mind, becoming part of what we sometimes call the memory of the muscles, and the needed correlation takes place with the will to bring about the result, or automatically. For a while, even after one has learned to hold on and keep his wheel moving, the exertion needed will be so great and his attention will be so absorbed in this, that he can look neither to right nor to left, nor notice what he passes.

But with continued effort, the knowledge required for the proper movement of the muscles becomes so fully stored in the subconscious memory that at length the learner may ride easily, indulging in other trains of thought and noticing persons and scenery. His hard-gotten knowledge has passed into skill.

So in learning to use a typewriter. We must at first find out, and with a separate effort strike the key for each separate letter. But as this knowledge takes its place in the subconscious memory, we merely think the word, and without further conscious direction, the fingers, as we need the letters, strike their keys.

This is how all skill is gained. We may see it in the child. We may see him gradually acquiring skill in doing things that we have forgotten that we ourselves had to learn how to do. When a new man comes into the world he seems to know only how to cry. But by degrees, and evidently in the same way by which so many of us over fifty have learned to ride a bicycle, he learns to suck; to laugh; to eat; to use his eyes; to grasp and hold things; to sit; to stand; to walk; to speak; and later, to read, to write, to cipher, and so on, through all the kinds and degrees of skill.

Now, because skill is that part of knowledge which comes closest to the individual, becoming as it were a part of his being, it is the knowledge which is longest retained, and is also that which cannot be communicated from one to another, or so communicated only in very small degree. You may give a man general directions as to how to ride a bicycle or operate a typewriter, but he can get the skill necessary to do either only by practice.

As to this part of knowledge at least, it is clear that the advances of civilization do not imply any gain in the power of the individual to acquire knowledge. Not only do antiquities show that in arts then cultivated the men of thousands of years ago were as skilful as the men of today, but we see the same thing in our contact with people whom we deem the veriest savages, and the Australian black fellow will throw a boomerang in a way that excites the wonder of the civilized man. On the other hand, the European with sufficient practice will learn to handle the boomerang or practise any of the other arts of the savages as skilfully as they, and wild tribes to whom the horse and firearms are first introduced by Europeans become excellent riders and most expert marksmen.

It is not in skill, but in the knowledge which can be communicated from one to another, that the civilized man shows his superiority to the savage. This part of knowledge, to which the term knowledge is usually reserved, as when we speak of knowledge and skill, consists in a knowing of the relation of things to other external things, and may, but does not always or necessarily, involve a knowing of how to modify those relations. This knowledge, since it is not concerned with the government of the organs directly responsive to the conscious will, does not come as close to the individual as skill, but is held rather as a possession of the organ of conscious memory, than as a part of the individual himself. While thus subject to loss with the weakening or lapse of that organ, it is also thus communicable from one to another.

Now, this is the knowledge which constitutes the body of knowledge that so vastly increases with the progress of civilization. Being held in the memory, it is transferable by speech; and as the development of speech leads to the adoption of means for recording language, it becomes capable of more permanent storage and of wider and easier transferability -- in monuments, manuscripts, books, and so on.

This ability to store and transmit knowledge in other and better ways than in the individual memory and in individual speech, which comes with the integration of individual men in the social body or body economic, is of itself an enormous gain in the advance of the sum of knowledge. But the gain in other and allied directions that comes from the larger and closer integration of individuals in the social man is greater still. Of the systematized knowledges, that which we call astronomy was probably one of the earliest. Consider the first star-gazers, who with no instrument of observation but the naked eyes, and no means of record save the memory, saw by watching night after night related movements in the heavenly bodies. How little even of their own ability to gather and store knowledge could they apply to the getting of such knowledge. For until civilization had passed its first stages, the knowledge and skill required to satisfy their own material needs must have very seriously lessened the energy that could be applied to the gaining of any other knowledge.

Compare with such an observer of the stars, the stargazer who watches now in one of the great modern observatories. Consider the long vistas of knowledge and skill, of experiment and meditation and effort, that are involved in the existence of the building itself, with its mechanical devices; in the great lenses; in the ponderous tube so easily adjusted; in the delicate instruments for measuring time and space and temperature; in the tables of logarithms and mechanical means for effecting calculations; in the lists of recorded observations and celestial atlases that may be consulted; in the means of communicating by telegraph and telephone with other observers in other places, that now characterize a well-appointed observatory, and in the means and appliances for securing the comfort and freedom from distraction of the observer himself! To consider all these is to begin to realize how much the cooperation of other men contributes to the work of even such a specialized individual as he who watches the stars.

Comments:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263