How to Fund

Transportation

That the public lands

of the United States belong to the people, and should not be sold to

individuals, nor granted to corporations, but should be held as a

sacred trust for the benefit of the people, and should be granted in

limited quantities, free of cost, to landless settlers.

- Free

Soil Party Platorm, 1852, incorporated with slight

modification into the Republican

Party platform of 1860

The veins through

which the life current of the country flows do not belong to the system

to which they are indispensable. Fancy a man whose arteries do not

belong to him, whose heart-beats are directed by another, by one over

whom he has no control, and the reader will form an idea of the

condition of this country, with the public highways in the hands of

corporations, acting independent of and, in some instances, in defiance

of the government.

The railroad and

telegraph system of the country are public highways. They take the

place of the canals, water-ways, and government roads of fifty years

ago. They have made it possible for the large cities to absorb the

mechanic and laboring population of the nation. All except tillers of

the soil are being allured into the cities, and soon there will be no

middle ground. It is the tendency of the times to build up cities, and

I see no great harm to follow if the connection between city and

country, between farm and factory, is steady, strong, and satisfactory

to both. It is not

satisfactory to-day, and will not be until those

for whom the railroads were built control them.

The Mississippi river

is a great national highway, and every year Congress makes

appropriations for its improvement. It belongs to no one, and is used

by all. It is public property. The man owning land along its banks can

not levy a tax on all that passes his door in boat or shallop. No

corporation would dare to absorb or control it, for the reason that it

is the means whereby the common business of the country on either side

of it for miles is carried....

These questions of

land and transportation go hand in hand, and are so closely allied that

they become one when studied. Being one question their proper solution

will cement, in indissoluble bond, the interests of the workers in

town, city, and country, whether their names are written as farmers,

mechanics, or laborers.

- Terence Powderly,

Thirty Years

of Labor, Chapter 8, "Land,

Telegraphy and Railroads"

Fundamentally, all law

recognizes the right to eminent domain, to take the portion of any

human being for the welfare of the public -- that no man's claim to any

portion of the earth shall stand in the way of the common good. This is

a common law, but in practice it only applies where a rich railroad

wants to get the land of some poor widow.

- Clarence Darrow, "How

to Abolish Unfair Taxation"

When the moguls

thought of profit, they did not think of the Penn

Central or the other railroads the company owned, like the Lehigh

Valley, or the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie or the Detroit, Toledo

&

Ironton. They thought of the rich parcels of land the railroad owned in

Chicago and Cleveland and Detroid and Pittsburgh, land that made the

railroad the largest real estate company in the nation.

- The Wreck of the Penn Central,

by By Joseph R. Daughen and

Peter Binzen, page 138

The merchant, the manufacturer, real-estate dealer and mechanic are all

benefited by whatever will tend to reduce the cost of car fare, gas,

water, garbage collection and taxes, while the owner of stock in a

street railway, gas or water company is interested to in have the cost

of these services as high as may be.... [Franchise owners] make a daily, hourly business of politics, raising up men in this

ward or that, identifying them with their machines, promoting them from

delegates to city conventions to city offices. They are always at work

protecting and building up a business interest that lives on through

its political strength. The watered securities of franchise

corporations are politics capitalized.

Regulation by city or commission will not correct these evils. The

more stringent the regulation, the more bitter will be the civic strife.

Only through municipal ownership can the gulf which divides the

community into a small dominant class on one side and the unorganized people on the other be

bridged; only through municipal ownership can the talent of the city be

identified with the interests of the city; only by making men's

ambitions and pecuniary interests identical with the welfare of the city

can civil warfare be ended. - Tom Johnson, Streetcar monopolist and mayor of Cleveland So

long as the State stands as an impersonal mechanism which can confer an

economic advantage at the mere touch of a button, men will seek by all

sorts of ways to get at the button, because law-made property is

acquired with less exertion than labour-made property. It is easier to

push the button and get some form of State-created monopoly like a

land-title, a tariff, concession or franchise, and pocket the proceeds,

than it is to accumulate the same amount by work. Thus a political

theory that admits any positive intervention by the State upon the

individual has always this natural law to reckon with.

|

Saving Communities

Bringing

prosperity through freedom, equality, local

autonomy and respect for the commons.

|

How to Fund Transportation

Nothing is more

important to civilization than transportation and communication, and,

apart from direct tyranny and oppression, nothing is more harmful to

the well being of a society than an irrational transportation system.

Trade is essential to economic vitality, and transportation is

essential to trade. This essay examines the irrationality of our

transportation system, the consequences of that irrationality, and,

most importantly, how our funding methods drive that irrationality. It also examines the

right to travel, established under common law, reasserted in the Magna

Carta, and recently eroded in the United States.

Today transportation is in crisis, partly because we

have ignored long recognized common-law principles. We

sketch the history of transportation only to illustrate

important principles that can save us from the current crisis.

Pittsburgh and Philadelhia, Pennsylvania are the primary examples we

use for discussing local transit, only because the author is from

Pittsburgh and has given seminars on transportation funding in

Philadelphia, and has better access to sources and examples in these

cities. Similar patterns apply in most US cities.

We will make the case that transprotation systems, and

particularly the rights of way themselves, should be publicly

owned and operated, and that they should be funded from a tax on the

land values they create. These principles apply

to all transportation systems, from airports to elevators, from

highways to canals and river locks. Our failure to adhere to these

principles throughout our history has turned our transportation systems

into opportunites for plunder and corruption.

Transportation and Land Use

Transportation dictates land use. Before the rise of

mechanization, travel over land was limited to the speeds and distances

that people and animals could walk, and freight was limited to what

they could pull. Towns and villages developed near waterways, and

profitable farms had to be located within hauling distance of the towns

and villages. Land just beyond the edge of towns had no value other

than farm value, and land more than a few miles from towns was not even

worth farming. The size of cities was therefore limited to the number

of people that could be

fed by nearby farms, except where food could be shipped by river. River

transporation was mostly for freight, and water freight (especially

crops, timber and minerals) mostly travelled downstream.

Trade between distant communities became possible

once sailing vessels harnessed wind power. Maritime empires

came to dominate earlier land-based empires, first along the

Mediterranean, where calm waters accommodated smaller, more primitive

sailing technology, and then along the Atlantic Coast of Europe, once

people learned to build and sail larger, ocean-worthy vessels. Ocean

trade made larger cities possible.

The American colonies developed after sailing technlogy

was well established, but before the advent of powered engines. Almost

all colonial cities developed next to natural harbors. New York, which

had the highest capacity deep-water harbor, has naturally become the

largest city in the United States.

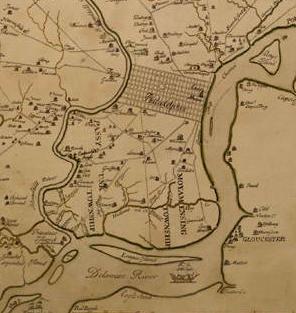

The location for Philadelphia was chosen based on its

access to both the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. Because the banks

where these rivers converged were swamplands, the city developed where

the rivers came closest to one another.

Transportation and Land Value

The most important determinant of land value is access

to population centers, and the best access to population centers is in

the population centers themselves. Population centers developed at

crossroads, confluences of navigable rivers,

and at harbors of oceans, seas and large lakes. The major exceptions

were where precious minerals were discovered; even in these exceptional

cases, establishing transportation became an immediate priority.

Land value increases with utility, but also with

scarcity. That is, land of similar qualities will be more expensive in

a region where good land is scarce. Holding land out of use increases

the scarcity of land that is available for use, artificially increasing

the price of land. In Europe, enclosure acts converted feudal lords

into land owners and crowded non-nobles into cities and towns. This

crowding drove rents up and wages down, triggering the poverty

associated with the Industrial Revolution.

It also triggered massive migration to North America,

where there was so much land that its monopolization would not become

as advanced as

in Europe for centuries. As land was so much cheaper, wages

went much further. Workers and entrepreneurs prospered

together. This period of low-rent, high-wage, high-profit prosperity

occured under both minimal government and minimal rents, in stark

contrast with the misery of workers in high-rent Europe. This era of

worker prosperity made Americans more receptive to the idea of

free-enterprise capitalism.

Migration was also accelerated by the ocean steamer,

which reduced ocean crossing times from six weeks down to six days.

However, the United States had the same basic land tenure system as

England, and speculators were rapidly grabbing up land, with the oldest

coastal cities becoming the most monopolized and the most expensive.

Transportation to more affordable inland settlements was still

expensive, and most immigrants arrived with barely enough money to get

a start in the coastal cities.

This rapid influx of stranded immigrants led

to sweatshop conditions and low wages in American port cities, but even

these wages were higher than in European cities. [Sombart]

Horace Greeley's

advice, "Go west, young man," was in recognition that wages

and opportunities are greater where land is less monopolized. The

United

States continued to be the "land of opportunity" until the frontier

closed. New transportation technology also brought rural land onto the

market and helped slow the rise of urban rents, especially with the

advent of the automobile.

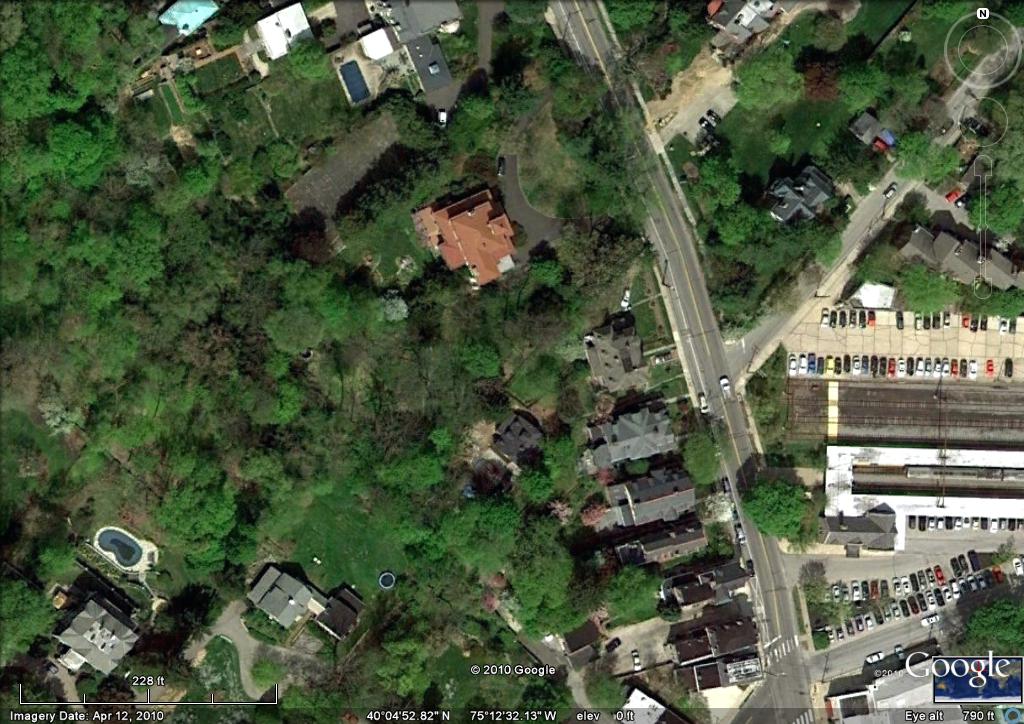

Rail lines turned idle farmland into affluent

neighborhoods. Railroad executives and their cronies bought up as much

land as they could before the public knew where the new lines would

run. Philadelphia millionaires built "summer homes" at the end of the

Reading Railroad's Chestnut Hill line, and Chestnut hill is

still the most affluent

neighborhood in Philadelphia.

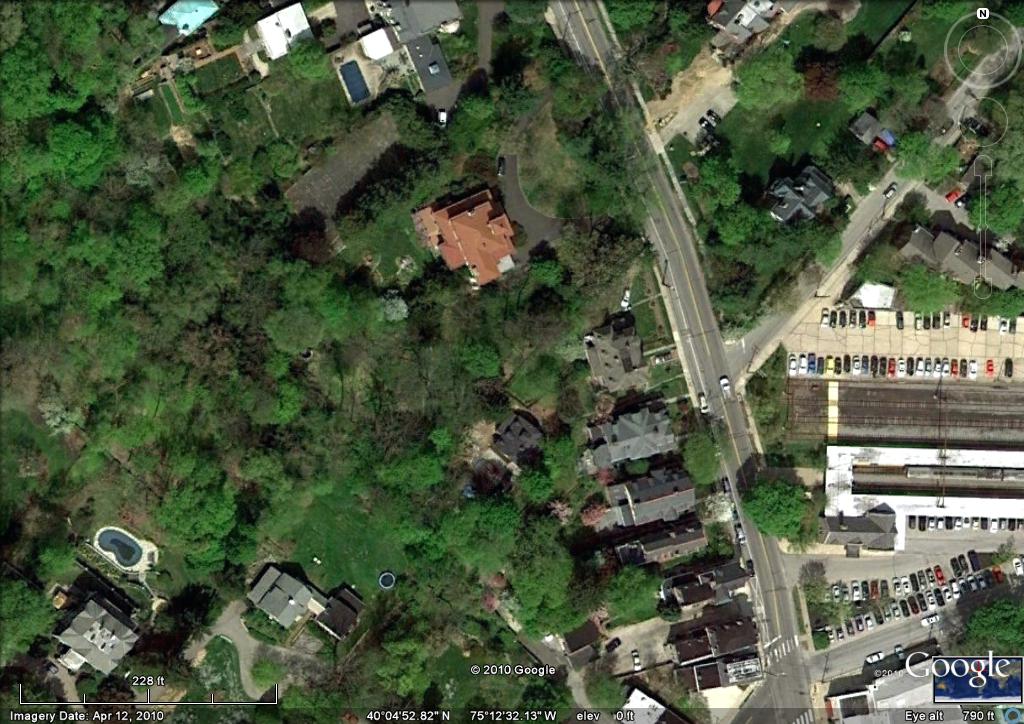

Some

of the Chestnut

Hill Mansions near Reading Station

Even

more affluent is Sewickley Heights, upwind of then-smoky Pittsburgh,

and just a short carriage ride from the Sewickley Station of the

Pennsylvania Railroad's commuter line. Although passenger trains no

longer to run Sewickley, it is still the most affluent neighborhood in

Pittsburgh's Allegheny County.

Speculation, transportation and monopoly

Canals, railroads, trolley lines, roads and

airports can dramatically increase the value of land served by them.

Those who who had acquired land before it was served by new

transportation systems reap what economists call "unearned increments"

in land value. The desire for such windfalls has perverted

transportation policy throughout history, especially when those who

have reaped the windfalls either had not paid for the transportation or

were

granted artificial privileges related to the transportation.

Transportation lines are "natural" monopolies in that

they require exclusive right-of-way grants. Monopoly prices are not

limited by competition, but by "whatever the market will bear."

Privately owned transportation lines are notorious for price-gouging

those who depend on the lines, to the detriment of the communities

served. In contrast, publicly owned lines are often subsidized in order

to keep rates down and encourage more people to use the lines. This is

rational if the subsidy increases land values by more than its cost. We

will dicuss this more in the context of the current transportation

crisis.

The era of private railroads and trolleys

Nothing exposes the folly of granting licensed

monopolies like the history of railroads and trolleys in the United

States.

Before the Civil War, most American roads and canals

were publicly

owned, but railroad rights of way were turned over to private

corporations following the English model. Most countries in continental

Europe retained ownership of the rights of way, sometimes allowing

private companies to maintain the rail and ballast on long-term leases

as common carriers. Competing companies could run rolling stock under

management of the leaseholding company. This arrangement made it easier

to nationalize railroads in continental Europe than in England and the

United States, where railroads hold right-of-way privileges in

perpetuity.

The Republican Party was formed as a coalition of

several reform parties. The largest of them was the Free Soil Party,

which opposed large land grants and instead advocated that land be

given in small grants to actual settlers. However, the Free Soil Party

also advocated the constrution of a transcontinental railroad to

provide more access to land, and the Republican party

embraced both positions. This attracted unscrupulous financiers to the

Republican

Party. The demands of the Civil War made the government so dependent on

financiers and industrialsts that, by the time the war was over, this

party of reformers was in the hands of the interests it had opposed.

The rush to build railroad empires was so great and the

politial influence of bankers and speculators so strong that the

country was rocked by scandal after scandal, involving massive land

grants and inflated subsidies, bribes and kickbacks to elected

officials, price gouging of farmers, ranchers and settlers, rate wars

designed to eliminate what little competition existed, and preferential

rates for "connected" customers. John D. Rockefeller's oil empire was

built by using his railroad power to see that competitors were

overcharged.

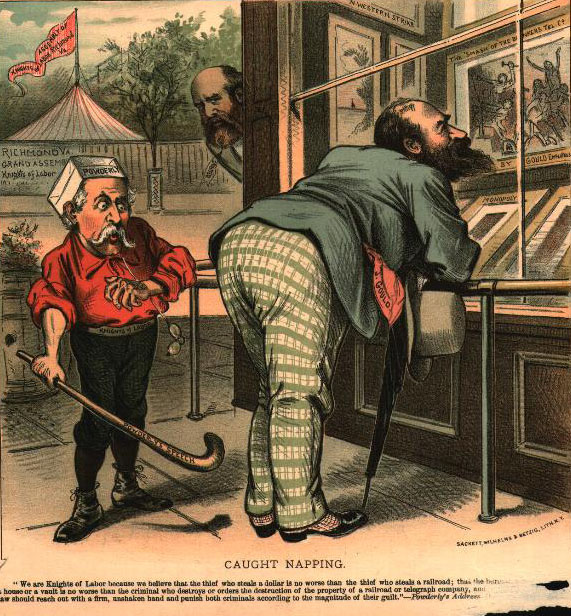

Henry George, who would become the most famous economic

reformer of the 1880s, began his reformist career in 1868 San

Francisco, with the article "What the

Railroad Will Bring Us," and Terence Powderly, as head of the

Knights of Labor, would launch the US labor movement on a platform

opposing land

monopoly, railroad and telegraph monopolies, and banking

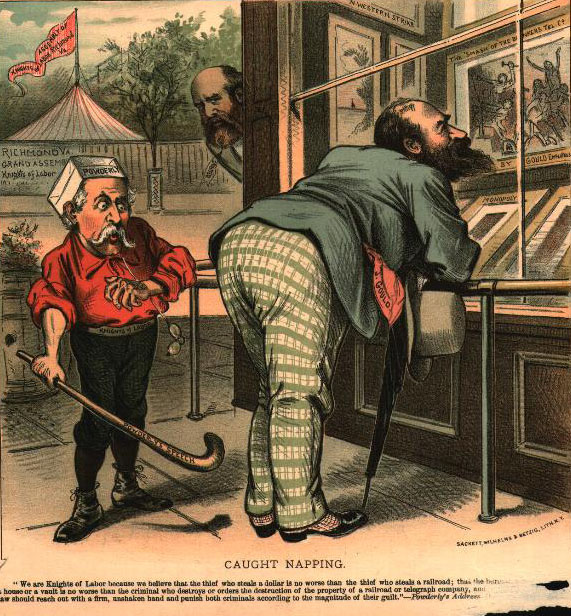

privilege. George and Powderly are featured below

in a front-cover

cartoon for Judge

Magazine, for taking on railroad monopolist Jay Gould.

In

the above cartoon,

while Jay Gould is admiring his monopolies and his smashed competition

and Henry George looks on, Terence Powderly is poised to give him a

good whacking with a cane labelled "Powderly's Speech."

The caption

reads: CAUGHT NAPPING: "We are Knights of Labor because we

believe that the thief who steals a dollar is no worse than the thief

who steals a railroad... and that the law should reach out with a firm,

unshaken hand and punish both criminals according to the magnitude of

their guilt." -

Powderly's Address

In the era of political machines, "patronage" meant

contract and franchise

patronage. The most lucrative franchises for New Yorks's Tammany Hall

bosses and their backers were streetcar franchises.

Overcharging for crowded

streetcars was so lucrative that the streetcar companies forced delays

in

construction of the New York subway system for more than a decade.

Finally, after the Belmont Company had effectively taken over most of

the city's streetcars, it engineered a deal where the city paid for the

construction of the subway and then turned it over to Belmont to run

for fifty years as a private monopoly. [McClure's]

The first major contract was with the Pennsylvania

Railroad to excavate the city and bring trains into Pennsylvania

Station. [History

of Tammany Hall]

Pennsylvania's major cities were even worse in some

ways, because the city, state and national governments had all been

under the same political party for over forty years and all

backed by the same corporate interests, and all cooperating with one

another. Like New York's Tammany Hall, Pennsylvania's machines were

based on contract and franchise patronage, with railroads leading the

way.

In the State ring are the

great corporations, the Standard Oil Company, Cramp's Ship Yard, and

the steel companies with the Pennsylvania Railroad at their head, and

all the local transportation and other public utility companies

following after. They get franchises, privileges, exemptions, etc.;

they have helped finance Quay through deals; the Pennsylvania paid

Martin, Quay said once, a large yearly salary; the Cramps get contracts

to build United States ships, and for years have been begging for a

subsidy on home-made ships. The officers, directors, and stockholders

of these companies, with their friends, their bankers and their

employees are of the organization. Better still, one of the local

bosses of Philadelphia told me he could always give a worker a job with

these companies, just as he could in a city department, or in the mint,

or post office.... The traction companies, which bought their

way from beginning to end by corruption, which have always been in the

ring and whose financiers have usually shared in other big ring deals,

adopted early the policy of bribing the people with" small blocks of

stock." ["Philadelphia:

Corrupt and Contented," by Lincoln Steffens]

Pittsburgh's experience was similar.

The railroads began the corruption of this

city. There "always was some dishonesty" as the oldest public men I

talked with said, but it was occasional and criminal till the first

great corporation made it business-like and respectable. The

municipality issued bonds to help the infant railroads to develop the

city, and, as in so many American cities, the roads repudiated the debt

and interest and went into politics. The Pennsylvania Railroad was in

the system from the start, and as the other roads came in and found the

city government bought up by those before them, they purchased their

rights of way by outbribing the older roads, then joined the ring to

acquire more rights for themselves and to keep belated rivals out....

The city paid in all sorts of rights and privileges, streets, bridges,

etc., and in certain periods the business interests of the city were

sacrificed to leave the Pennsylvania Road in exclusive control of a

freight traffic it could not handle alone.["Pittsburg:

A City Ashamed" Steffens]

Mayor Magee and his partner, Flinn, were not content

with giving

plums to cronies. Rather, they took the best plums (including streetcar

lines) for themselves.

Magee took the financial and corporate branch,

turning

the streets to his uses, delivering to himself franchises, and building

and running railways. Flinn went in for public contracts for his firm,

Booth & Flinn, Limited, and his branch boomed. Old streets were

repaired, new ones laid out; whole districts were improved, parks made,

and buildings erected. The improvement of their city went on at a great

rate for years, with only one period of cessation, and the period of

economy was when Magee was building so many traction lines that Booth

& Flinn, Ltd., had all they could do with this work.

Magee did not steal franchises and sell them. His councils gave them to

him. He and the busy Flinn took them, built railways which Magee sold

and bought and financed and conducted, like any other man whose

successful career is held up as an example for young men. His railways,

combined into the Consolidated Traction Company, were capitalized at

$30,000,000. The public debt of Pittsburg is about $18,000,000, and the

profit on the railway building of Chris Magee would have wiped out the

debt. "But you must remember," they say in the Pittsburg banks, "that

Magee took risks and his profits are the just reward of enterprise."[ibid.]

This pattern ofstate and municipal corruption tied to

private railroads and streetcars was repeated in state after state and

city after city, but three states, California, Minnesota and Ohio, are

worth noting, not because they are the three worst, but because their

stories are the most interesting and have the most bearing on current

debates.

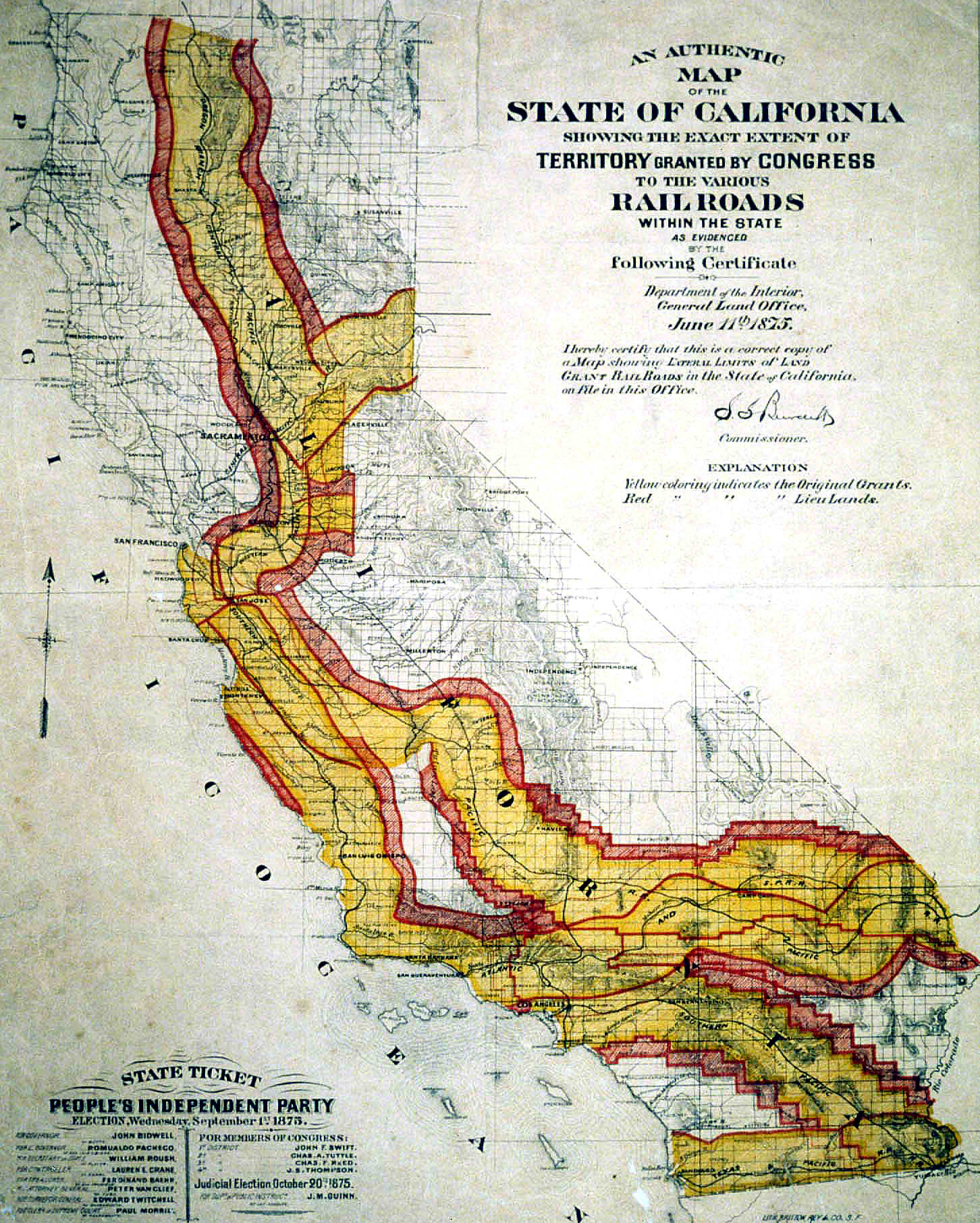

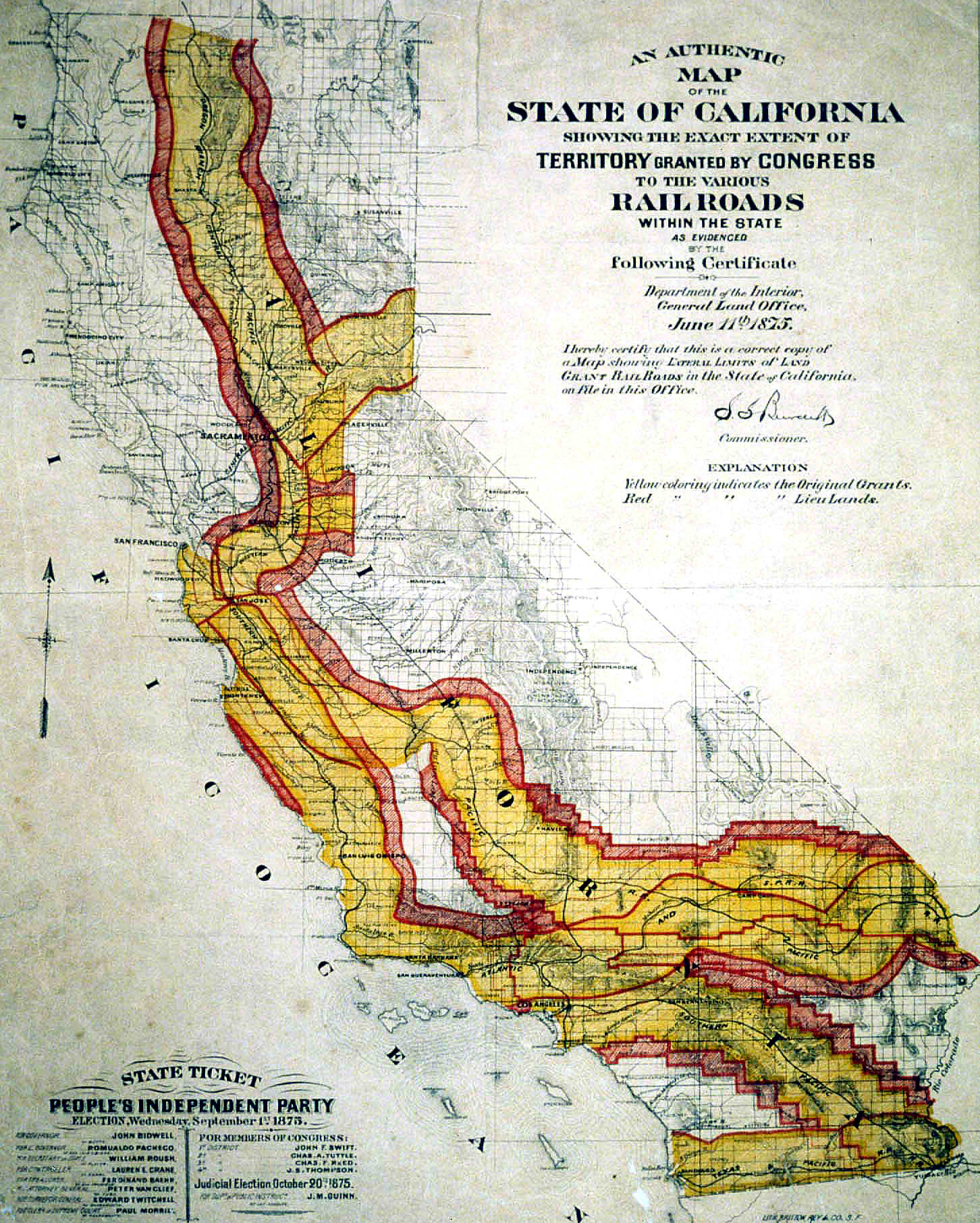

However, California actually is the worst state

for railroad domination, and has been ever since massive land grants

were given to promote the trans-continental railroad. Henry George's

predictions in ""What

the

Railroad Will Bring Us" turned out to be accurate in every

detail, except that the railroad domination was even worse than George

had predicted. Instead of giving railroads to California, Congress gave

California to the railroads.

Map

of Congressional land grants to railroads as of 1875, prepared

by the Secretary of the Interior.

Railroads have ruled California politics ever since. The Union

Pacific Railroad still owns more California land than all of its home

owners combined. California's Proposition 13, which curtailed the

proprety tax, actually increased home owners' share of the tax

burden by dramatically reducing taxes for the Union Pacific and other

land-rich corporations. It also launched Henry George on a crusade that

would make him "the prophet of San Francisco," the most famous American

reformer of the 1880s, beginning with the book, Our Land and Land Policy. Minnesota was the nexus for J. J. Hill's Great Northern Railway. Hill is ballyhooed

by conservative libertarians as an example of free enterprise

railroading for building the only transcontinental railroad that took

no public money, got relatively few land grants, and never went

bankrupt. However, he got his start buying earlier railroads which had

gotten public money and large land grants, and which had gone bankrupt.

(He bought them out of bankruptcy.) His railroad went

transcontinental in 1893, after the country had been shocked by

previous abuses and had turned decidely anti-railroad. Hill employed a

"swarm of lobbyists" in St. Paul, urging the state legislature not only

to grant rights of way to his railroad, but to block rights of way to

other railroads. He was also in partnership with J. P. Morgan, head of

the notoriously corrupt Pennsylvania RR. Whether credit belongs

to Hill, to a change in national mood, or to the good sense of the

people of Minnesota and their leaders, the Great Northern shows

that a transcontinental railroad would have been built within a

reasonale time without the massive massive subsidies that went to the

Union Pacific. OhioOhio is probably the most interesting

state of all, due to Cleveland's "trolley wars" between two political

giants who were also Cleveland's two largest trolley millionaires.

Nowhere was the battle for against private streetcar franchises as

notorious as it was in Cleveland. Mark Hanna was the consummate salesman, negotiator and political operative.

He dominated the Ohio state political machine as its recognized "boss"

and became nationally famous for managing McKinley's successful

Presidential campaign. Hanna raised unprecedented campaign funds by

villainizing William Jennings Bryan and appealing to banking and other

monopoly interests who feared Bryan's monetary reforms. Getting streetcar franchises for himself was consistent with Hanna's idea of politics for profit. Tom

Johnson, on the other hand, was an experienced streetcar

superintendent and innovator with little interest in politics. He had

invented the "Johnson Farebox,"

which became the national standard for streecars for well over half a

century. His other inventions included steel streetcar rails that

greatly outlasted the iron rails everyone had been using, flush-laid

tracks that were much easier for wagons to cross, a

submerged-cable

system for on-street cable cars, free transfers for users of multiple

streetcars and buses, and, believe it or not, the first

magnetic levitation system. (He sold his maglev patents to General

Electric.) After

taking over a struggling line in Indianapolis, improving management and

making it profitable, Johnson thought he could do well running

streetcars in Cleveland, which "had eight differentstreet

railroad

companies "owned by bankers, politicians, business and professional men

who had been successful in various undertakings, but without a street

railroad man in the entire list." Mark Hanna, politically quashed

Johnson's bid for a franchise to an userved neighborhood in 1879, and

taught the twenty-five-year-old Johnson the importance of political

connections. Johnson bought out a troubled line in Cleveland and

proceeded to battle with Hanna. Johnson and Hanna eventually emerged as

the owners of Cleveland's only two remaining street railway companies,

but Johnson held 60% of the business to Hanna's 40%. He eventually

found allies in Hanna's partners, and consolodated everything into one

company, with Hanna's influence greatly diminished. [My Story, Chapter 9] The Johnson Company had also acquired franchises in St.

Louis, Detroit and other cities, and had built two steel mills and two

company towns. Between franchise monopolies, patent monopolies and land

speculation, Johnson had become one of America's youngest

multi-millionaires. This would have been just another contest between monopolists if Johnson had not read Social Problems and then Progress and Poverty,

both by the reformer Henry George. George's writings convinced Johnson,

his partner Arthur Moxham and his lawyer L. A. Russell, that the

Johnson Company's fortunes were based largely on the exploitation of

privilege and greatly exceeded his contributions to society. Johnson

became George's biggest financial backer and an outspoken advocate of

land value tax and the municipal ownership of public utilities,

including streetcar lines. He then entered politics, as an "anti-monopolist monopolist," repudiating the privileges from which his own fortunes derived. He served in Congress from 1891 through 1895, and as mayor of Cleveland from 1901 through 1909. People

who follow US national politics today might get an idea of how

different these two rivals were from modern figures who emulate them.

Republican operative Karl Rove has described Hanna as his personal role

model, and Democratic congressman Dennis Kucinich has said the same of

Tom Johnson. http://home.comcast.net/~zthustra/pdf/a_program_for_monetary_reform.pdf

transfers, |

Navigation

We Provide

How You Can Help

- Research

- Outreach

- Transcribing Documents

- Donating Money

- Training for Responsibility

Our Constituents

- Public Officials

- Small Businesses

- Family Farms

- Organic Farms

- Vegetarians

- Labor

- Real Estate Leaders

- Innovative Land Speculators

- Homeowners

- Tenants

- Ethnic

Minorities

- Ideological Groups

Fundamental Principles

- Decentralism and Freedom

- Focusing on Local Reform

- Government as Referee

- Government as Public Servant

- Earth as a Commons

- Money as a Common Medium

- Property Derives from Labor

Derivative Issues

- Wealth Concentration

- Corruption

- Bureaucracy

- Authorities

- Privatization

- Centralization

- Globalization and Trade

- Economic Stagnation

- Boom-Bust Cycles

- Development Subsidies

- Sprawl

- Gentrification

- Pollution and Depletion

- Public Services

- Transportation

- Education

- Health Care

- Retirement

- Wages

- Zoning

- Parks

- Shared Services

Blinding Misconceptions

- Orwellian Economics

- Corporate Efficiency

- Democracy vs. Elections

- Big Government Solutions

- Founding Fathers

- Politics of Fear

- Politics of Least Resistance

- Radical vs. Militant

- Left vs. Right

- Common vs. Collective

- Analysis vs. Vilification

- Influence vs. Power

|