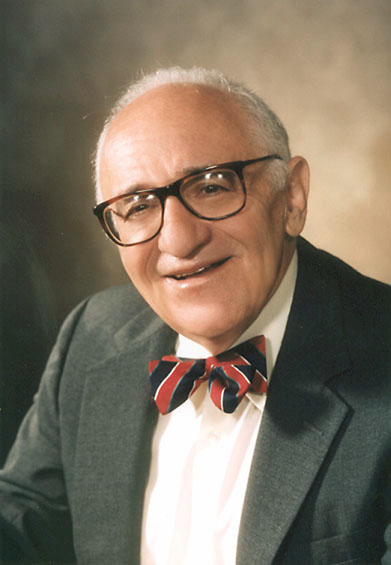

Murray Rothbard's Facile Critique

|

Saving Communities

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

Murray Rothbard's Facile Single-Tax Critiqueby Dan Sullivan January 17, 2020 Rothbard's original article was written in 1957 and appears here: "The Single Tax: Economic and Moral Implications" |

|

Overview

Murray Rothbard's objections are primarily ideoogical, but

based on a failure to understand what the single tax proposal is, a

failure to understand how price is derived from rent and not the other

way around, a failure to understand market mechanisms, a failure to

distinguish the land owner from the land user, and a failure to distinguish common rights from collective rights.

Rothbard's Critique Verbatim

|

Analysis of Each Paragraph

|

|

Seventy-five years ago, Henry George spelled out his "single tax" program Progress and Poverty, one of the best-selling economic works of all time. According to E.R. Pease, socialist historian and long-time secretary of the Fabian Society, this volume "beyond all question had more to do with the socialist revival of that period in England than any other book." |

This is Rothbard's attempt to impugn George to his anti-socialist audience by implying that, since some socialists agreed with George, he must have been a socialist. In fact, while socialists gave feint praise to George for increasing public awareness of justice issues, they consistently attacked his actual proposal. George was also a consistent opponent of socialism and advocate of the free market. The great libertarian Albert Jay Nock wrote,

Marx, on the other hand, dismissed Progress and Poverty as "the

capitalist's last ditch." |

|

Most present-day economists ignore the land question and Henry George altogether. Land is treated as simply capital, with no special features or problems. Yet there is a land question, and ignoring it does not lay the matter to rest. The Georgists have raised, and continue to raise, questions that need answering. A point-by-point examination of single-tax theory is long overdue. |

Rothbard's claim that "most present-day [1957] economists ignore the land question and Henry George altogether" is exaggerated, to say the least. Samuelson's Economics, first published in 1948, was the best-selling economics text for decades. It included an entire chapter dedicated to land as a distinct factor of production and a discussion of George's single tax. Rothbard was correct that an examination of single-tax

theory

would be useful, but, as can be seen below, he mostly examined his own

imagination, making errors that could have been easily caught with a

little fact-checking. |

|

According to the single-tax theory, individuals have the natural right to own themselves and the property they create. Hence they have the right to own the capital and consumer goods they produce. Land, however (meaning all original gifts of nature), is a different matter, they say. Land is God-given. Being God-given, none can justly belong to any individual; all land properly belongs to society as a whole. |

That is also a

foundation of the Judeo-Christian ethic and a cornerstone of classical

liberalmism as expressed by John Locke, William Penn,

François "laissez faire" Quesnay, Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, Ben

Franklin, Tom Paine, Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, and many others

took this view. Also, Georgist do not believe that land "belongs to society as a whole" in

any collectivist sense, but rather is an asset to which each individual

has a right of access, limited only by the equal rights of others. (See "Common Rights

vs. Collective Rights.") |

|

Single taxers do not deny that land is improved by man; forests are cleared, soil is tilled, houses and factories are built. But they would separate the economic value of the improvements from the basic, or "site," value of the original land. The former would continue to be owned by private owners; the latter would accrue to "society" — that is, to society's representative, the government. Rather than nationalize land outright, the single taxers would levy a 100 percent tax on the annual land rent — the annual income from the site — which amounts to the same thing as outright nationalization. |

Actually, the term "single taxer" does not mean

an advocate of collecting 100% of the value of land, but only of

replacing all other

taxes with a land value tax. As the transition would be gradual, it

would be easy as the shift proceeds to determine how close we could get

to 100% without the

risk of exceeding it in some cases. George explicitly stated that

collecting 100% of the rent was not necessary. Furthermore, assessing and collecting the rent does not amount "to

the same thing as outright nationalization." This is clear from

George's objections to nationalization, and from socialist

condemnations of George for opposing nationalization. Nationalization

gives government far more control over how land is used than a mere

land value tax gives it. |

|

Georgists anticipate that the revenue from such tax on land would suffice to conduct all the operations of government — hence the name "single tax." As population increases and civilization develops, land values (especially urban site values) increase, and single taxers expect that confiscation of this "unearned increment" will keep public coffers overflowing far into the future. The increment is said to be "unearned" because it stems from the growth of civilization rather than from any productive activities of the site owner. |

There is no desire by Georgists to "keep public

coffers overflowing." To the contrary, George argued that, TO prevent government from becoming corrupt and tyrannous, its organization and methods should be as simple as possible, its functions be restricted to those necessary to the common welfare, and in all its parts it should be kept as close to the people and as directly within their control as may be. (- Social Problems, chapter 17, "The Functions of Government") Any excess revenue, George noted, could be distributed

on a per capita basis, with minimal bureaucratic involvement. |

|

Almost everyone would agree that the abolition of all the other taxes would lift a great blight from the energies of the people. But Georgists generally go beyond this to contend that their single tax would not harm production — since the tax is only levied on the basic site and not on the man-made improvements. In fact, they assert the single tax will spur production; it will penalize idle land and force landowners to develop their property in order to lower their tax burden. |

It is interesting that Rothbard endorsed replacing all other taxes with land value tax, which was George's core proposal, even as this essay tries to discredit that proposal. In fact, land value tax has spurred production wherever it

has been applied, even in small doses. See "Higher

Taxes that Promote Development," in Fortune,

August 8, 1983 |

|

Idle land, indeed, plays a large part in single-tax theory, which contends that wicked speculators, holding out for their unearned increment, keep sites off the market, and cause a scarcity of land; that this speculation even causes depressions. A single tax, confiscating unearned increment, is supposed to eliminate land speculation, and so cure depressions and even poverty itself. |

This appears to be Rothbard's empty sarcasm, for neither George nor his most prominent followers ever called landlords or speculators "wicked" or any synonym for "wicked." Winston Churchill expressed the spirit of Georgist reform when he said,

Also the point is to end monopolization, not speculation.

Speculation simply means "looking forward," and land value tax leads to

more speculation than ever, but changes the nature of that speculation.

Instead of looking to buy land in the path of progress and then get

paid to get out of the way, the speculator looks to buy land that

will remain suitable for the use to which he wants to put it. Thus, he

might choose a spot that he believes will be suitable for a hotel in

five years, but only if he intends to build such a hotel.

|

|

How can the single taxers give such importance to their program? How can they offer it as a panacea to end poverty? A clue may be found in the following comments about the plight of the undeveloped countries: Most of us have learned to believe that the people of … so-called backward nations are poor because they lack capital. Since … capital is nothing more than … human energy combined with land in one form or another, the absence of capital too often suggests that there is a shortage of land or of labor in backward countries like India or China. But that isn't true. For these "poor" countries have many times more land and labor than they can use … they have everything it takes — both land and labor — to produce as much capital as people anywhere.1 |

Rothbard portrays the idea of poverty resulting from land monopoly as a as an invention of George and his single-taxers, but that is untrue. William Penn wrote,

Adam Smith wrote,

Thomas Jefferson wrote,

Ben Franklin wrote,

Tom Paine wrote,

|

|

And since these countries have plenty

of land and labor,

the trouble

must be idle land withheld from production by speculative landlords! The deficiency in that argument is the neglect of the time factor in production. Capital is the product of human energy and land — and time. The time-block is the reason that people must abstain from consumption, and save. Laboriously, these savings are invested in capital goods. We are further along the road to a high standard of living than India or China because we and our ancestors have saved and invested in capital goods, building up a great structure of capital. India and China, too, could achieve our living standards after years of saving and investment. |

If Rothbard had read just a little further, he would have seen his objection answered in the very next paragraph: We know that many British and American stockholders have built huge fortunes through their investments in broken-down India. Most of the powerful nations of Europe, as well as Japan and the United States, have helped their businessmen draw billions of dollars out of the "poor" land and labor of China. Many American fortunes have been made out of Mexican mineral lands worked by Mexican labor; and yet such fortunes are as nothing when compared with the great wealth accumulated by a few "high born" Mexican families who have always been supported by handily corrupt politicians. Obviously, the wealth from which capital comes is produced in the "poor" countries; but, by some means or other, enough of it just doesn't seem to fall into the pockets of enough of the people of those countries so that they might accumulate a surplus to use as capital. Apparently he did not want

his objection answered, and didn't actually want to understand the

point of the passage he was quoting. He just wanted to take a quote out

context and sneer at it. Nor was there any "neglect of the time factor in production" by George. Rather, the neglect was in Rothbard's failure to actually read George for himself. George dedicates an entire chapter of Progress and Poverty to the role of time preference in determining interest. Similarly, Book 3, Chapter 8 of George's The Science of Political Economy is titled, "The Relation of Time In Production." Of course capital is the product of human energy and land over time. Does Rothbard seriously imagine Georgists don't know that? Does he not realize that land value tax is levied in proportion to the length of time during which the land is held? And does he imagine that the people of these once-great civilizations did not save and invest because it did not occur to them? Does he not realize that people who were continuously fleeced of their earnings by landlords could not save and invest, and that the landlords themselves were too rich, lazy or over-committed to invest successfully? |

|

The single-tax theory is further defective in that it runs up against a grave practical problem. How will the annual tax on land be levied? In many cases, the same person owns both the site and the man-made improvement, and buys and sells both site and improvement together, in a single package. How, then, will the government be able to separate site value from improvement value? No doubt, the single taxers would hire an army of tax assessors. But assessment is purely an arbitrary act and cannot be anything else. And being under the control of politics, it becomes purely a political act as well. Value can only be determined in exchange on the market. It cannot be determined by outside observers. |

The "grave practical problem" exists only in Rothbard's imagination. He asserts that land and building values cannot be separately assessed, when in fact that is the only way they can be assessed, and it is, in fact, the way they are assessed even when the same tax rate is applied to both. Anyone who understands differential equations knows that you can determine separate values mathematically given multiple samples. You don't even need two different buildings on identical land or two parcels with identical buildings. The fact that Rothbard does not know how this is done, and never bothered to find out, says more about Rothbard than about assessing. His notion that "No doubt, the single taxers

would hire an army of tax assessors," is the exact opposite of what we

would do. There is already an army of property tax assessors, and as

assessing land is so much easier and accurate than assessing

improvements, we would actually need fewer assessors under a land value

tax than we now need under a property tax. Moreover, the army

bureaucrats that assesses, collects and enforces other taxes could be

dispensed with. Finally, he ways that "value can only be determined by

exchange on the market. It cannot be determined by outside observers."

But that is exactly what the outside observers base assessments on:

statistical analysis of exchanges on the market. |

|

In the case of agricultural land, for instance, it is clear that you cannot, in practice, separate the value of the original ground from the value of the cleared, prepared, and tilled soil. This is obviously impossible, and even assessors would not attempt the task. |

Assessors do it all the time.Rural assessors, and rural farmers, for that matter, know very well what it costs to convert raw land into farmland, and tailor their estimates accordingly. Rothbard is just blowing smoke. |

|

"It is a fact that there is more land available in the world, even quite useful land, than there is labor to keep it employed. This is a cause for rejoicing, not lament." |

The quotation marks suggest that he is quoting a

Georgist, or at least quoting someone, but there are no attributions to

these quotes, and it seems that he is quoting his own straw men. In

this case, it is true that there is more land than labor to keep it

employed, but only if landlords are prevented from holding prime land out of use. In any case, what makes Rothbard's claim false

is the word "available." His

notion had already been debunked by his predecessor, Albert Jay Nock

(for whom

Rothbard had high praise):

Ralph Waldo Emerson made the same point long before

that. "I find this vast network, which you call property, extended over the whole planet. I cannot occupy the bleakest crag of the White Hills or the Alleghany Range, but some man or corporation steps up to me to show me that it is his. Now, though I am very peaceable, and on my private account could well enough die, since it appears there was some mistake in my creation, and that I have been _mis_sent to this earth, where all the seats were already taken, — yet I feel called upon in behalf of rational nature, which I represent, to declare to you my opinion, that, if the Earth is yours, so also is it mine. All your aggregate existences are less to me a fact than is my own; as I am born to the earth, so the Earth is given to me, what I want of it to till and to plant; nor could I, without pusillanimity, omit to claim so much. I must not only have a name to live, I must live. My genius leads me to build a different manner of life from any of yours. I cannot then spare you the whole world. I love you better. I must tell you the truth practically; and take that which you call yours. It is God's world and mine; yours as much as you want, mine as much as I want. Besides, I know your ways; I know the symptoms of the disease. To the end of your power, you will serve this lie which cheats you. Your want is a gulf which the possession of the broad earth would not fill. Yonder sun in heaven you would pluck down from shining on the universe, and make him a property and privacy, if you could; and the moon and the north star you would quickly have occasion for in your closet and bed-chamber. What you do not want for use, you crave for ornament, and what your convenience could spare, your pride cannot." ("The Conservative")

|

|

But the single taxers are also interested in urban land where the value of the lot is often separable, on the market, from the value of the building over it. Even so, the urban lot today is not the site as found in nature. Man had to find it, clear it, fence it, drain it, and the like; so the value of an "unimproved" lot includes the fruits of man-made improvements. |

This

"clearing" value is a trivial portion of land value in urban

areas. The value

of urban land does indeed include the fruits of man-made improvements,

but

those improvements were made by surrounding landholders, not the holder

of the vacant lot. While the Empire State building (or the Waldorf

Astoria before it) added tremendous value to any vacant lots around it,

vacant lots did not add value to the Empire State Building. |

|

Thus, pure site value could never be found in practice, and the single-tax program could not be installed except by arbitrary authority. But let us waive this fatal flaw for the moment and pursue the rest of the theory. Let us suppose that pure site value could be found. Would a single-tax program then be wise? |

There is no need to waive anything, because centuries of

assessment history show that Rothbard is wrong. But, as he wants to

move on to other errors for us to correct, we shall indulge him. |

Well, what about idle land? Should the sight of it alarm us? On the contrary, we should thank our stars for one of the great economic facts of nature: that labor is scarce relative to land. It is a fact that there is more land available in the world, even quite useful land, than there is labor to keep it employed. This is a cause for rejoicing, not lament. |

The tragedy is not that there is idle land, but that

there is involuntarily idle labor. If "labor is scarce relative to

land," how is it that land has become so expensive that labor is

prevented from working that land? And why should people who are forced

into poverty consider it a "cause for rejoicing" that their access

to this plentiful land is denied them? |

Since labor is scarce relative to land, and much land must therefore remain idle, any attempt to force all land into production would bring economic disaster. Forcing all land into use would take labor and capital away from more productive uses, and compel their wasteful employment on land, a disservice to consumers. |

There is no proposal to force all land into production,

or even to tax all land, but only to tax land that has rental value,

and only in proportion to that value. As people let go of the most

valuable unused land, and that land is put to use by others, there is far less resorting to poorer

land, and the poorer land becomes free or nearly free. Then labor and

capital is first applied to the best land, where it will do the most good. That is the opposite of Rothbard's claim. Land value is based on the well accepted economic

principle known as "Ricardo's

Law of Rent," which John Stuart Mill called "the pons asinorum" (bridge

of asses) of economics. It means a bridge that asses will not cross,

which is an apt description of Rothbard's failure in this essay. |

|

The single taxers claim that the tax could not possibly have any ill effects; that it could not hamper production because the site is already God-given, and man does not have to produce it; that, therefore, taxing the earnings from a site could not restrict production, as do all other taxes.2 This claim rests on a fundamental assumption — the hard core of single-tax doctrine: Since the site-owner performs no productive service he is, therefore, a parasite and an exploiter, and so taxing 100 percent of his income could not hamper production. |

This paragraph has multiple errors. Nobody has ever claimed that land value tax "could not possibly have any ill effects." However, it has been in place for well over a century, and the few ill effects it had were transitional and heavily outweighed by immediate positive benefits. Wherever it had been levied, production has increased, even where other taxes had not been reduced. Land value tax is not "taxing the earnings from a site," but is a tax on the unimproved value. The tax is exactly the same whether the landholder earns anything or not, and does not tax "100 percent of his income" or any measurement of his income. Finally George never called landholders parasites or exploiters. Rothbard is determined to paint the Georgist proposal as an ad hominem attack on landholders when it is proposed as a reform of the system. |

|

But this assumption is totally false. The owner of land does perform a very valuable productive service, a service completely separate from that of the man who builds on, and improves, the land. The site owner brings sites into use and allocates them to the most productive user. He can only earn the highest ground rents from his land by allocating the site to those users and uses that will satisfy the consumers in the best possible way. We have seen already that the site owner must decide whether or not to work a plot of land or keep it idle. He must also decide which use the land will best satisfy. In doing so, he also ensures that each use is situated on its most productive location. A single tax would utterly destroy the market's important job of supplying efficient locations for all man's productive activities, and the efficient use of available land. |

Here Rothbard conflates the landowner with the land user. Yes, there are many productive things a land user can do other than build on and improve the land, but all the land owner does in his capacity as owner, is give permission to whomever he turns out to be the highest bidder. The highest bidder is the actual land user, and he will put the land to the same use no matter who gets his payments. In most cases, the person who is no longer using the land will turn it over to a new user in order to avoid paying taxes on it, and he will also accept the highest offer. Assessments of market value are not based on single transactions, but on averages of many similar transactions. Therefore, a user who as a particularly good use for a parcel will not have to pay the full value of his superior use, whether to the previous landholder or to government. His ability to find a superior use for the land will accrue to him alone. Rothbard fails to recognize that a land value tax is not a tax on use, but a tax on excluding others from use. It is exactly the same no matter how efficiently the land is used. Therefore, whoever uses land most efficiently will prosper, contrary to Rothbard's suppositions. Rothbard's claims are about supplying efficient locations is observably false, in that land

falls into the hands of

productive users far more efficiently where its value is taxed. Thus we

see that 17 Pennsylvania cities all had surges in construction and

renovation when those cities increased their taxes on land value, and

we see similar effects in the municipalities of Australia in the '50s

through the '70s when those municipalities completely replaced property

taxes with land value taxes.

|

|

A 100 percent tax on rent would cause the capital value of all land to fall promptly to zero. Since owners could not obtain any net rent, the sites would become valueless on the market. From that point on, sites, in short, would be free. Further, since all rent would be siphoned off to the government, there would be no incentive for owners to charge any rent at all. Rent would be zero as well, and rentals would thus be free. The first consequence of the single tax, then, is that no revenue would accrue from it. Far from supplying all the revenue of government, the single tax would yield no revenue at all. For if rents are zero, a 100 percent tax on rents will also yield nothing. |

Neither George nor leading Georgists have ever proposed

an abrupt shift to the single tax. Therefore, the tax would not

"promptly" do anything. Rothbard also conflates the capitalized value

of the expected land rent with the land rent itself, leading to absurd results. When

the rent is forwarded to government as a land value tax, it lowers what

people will pay for land as a purchasing price, but it does not lower

the actual rents; it only changes who the ultimate recipient of those

rents will be. For

example, we know that people already hold leased land, not to get

an unearned income, but to put the land to use. If someone buys the

lease, he does not pay as much as if he were to buy the land outright.

None the less, he must buy the lease in order to use the land, just as

he would do if he had to buy the land outright. It happens all the

time; many commercial buildings, including the Empire State building,

are built on leased land. |

|

In our world, the only naturally free goods are those that are superabundant — like air. Goods that are scarce, and therefore the object of human action, command a price on the market. These goods are the ones that come into individual ownership. Land generally is abundant in relation to labor, but lands, particularly the better lands, are scarce relative to their possible uses. All productive lands, therefore, command a price and earn rents. Compelling any economic goods to be free wreaks economic havoc. Specifically, a 100 percent tax means that land sites pass from individual ownership into a state of no-ownership as their price is forced to zero. Since no income can be earned from the sites, people will treat the sites as if they were free — as if they were superabundant. But we know they are not superabundant; they are highly scarce. The result is to introduce complete chaos in land sites. Specifically, the very scarce locations — those in high demand — will no longer command a higher price than the poorer sites. |

Now Rothbard is running with his error, for nobody proposes to make land free. The proposal is that the landholder pays the market rent to the government instead of to the prior landholder. He also repeats his error that "no income can be earned from the sites." Income is already earned from rented sites, so his assertion is empirically false was well as logically false. The best sites will command the highest rents. Air is not free because it is more abundant than land, but because nobody has title to it.

|

|

"Not only will there be no incentive for those in power to allocate the sites efficiently, there will also be no market rents and therefore no way that anyone could find out how to allocate sites properly." |

This appears to be Rothbard quoting his straw man again.

Land value tax does not propose that "those in power" allocate sites at

all. The previous site holder turns over his lease as he sells his

improvements. On those occasions when previous owners walk away from

sites, the sites are simply auctioned off and go to whoever bids the

highest rent for each site. |

|

Therefore, the market will no longer be able to ensure that these locations will go to the most efficient bidders. Instead, everyone will rush to grab the best locations. A wild stampede will ensue for the choice downtown urban locations, which will now be no more expensive than lots in the most dilapidated suburbs. There will be great overcrowding in the downtown areas and underuse of outlying areas. As in other types of price ceilings, favoritism and "queuing up" will settle allocation, instead of economic efficiency. In short, there will be land waste on a huge scale. Not only will there be no incentive for those in power to allocate the sites efficiently, there will also be no market rents and therefore no way that anyone could find out how to allocate sites properly. In brief, the inevitable result of a single tax would be nothing less than locational chaos. And since location — land — must enter into the production of every good, chaos would be injected into every aspect of economic calculation. Waste in location leads to waste and misallocation of all productive resources. |

Again

Rothbard runs amok based on his fundamental

misunderstanding of the process. He also confuses the most efficient

users with the highest bidders. Those two tend to be the same people,

but calling them "the most efficient bidders" makes no sense. In any

case, his "wild stampede" is pure fantasy. People will bid as before,

but they will bid rents, not prices. Rothbard's entire rant is based on

his not grasping what the proposal is in the first place. |

|

The government, of course, might try to combat the disappearance of market rentals by levying an arbitrary assessment, declaring by fiat that every rent is "really" such and such, and taxing the site owner 100 percent of that amount. Such arbitrary decrees would bring in revenue, but they would only compound chaos further. Since the rental market would no longer exist, the government could never guess what the rent would be on the free market. Some users would be paying a tax of more than 100 percent of the true rent, and the use of these sites would be discouraged. Finally, private owners would still have no incentive to manage and allocate their sites efficiently. An arbitrary tax in the face of zero rentals is a long step toward replacing a state of no-ownership by government ownership. |

More

hysterical ranting based on ignorance of assessing

methodology, and failing to grasp that land price is a capitalization

of projected future rents. Rents do not depend on price, but rather

price

depends on expected rents. The renter does not care what price

the owner paid, but a prospective owner cares very much what rents he

expect to get. It is the price, not the rents, that are speculative.

Because of thise, rents can be assessed directly with greater

accuracy than price. |

|

In this situation, the government would undoubtedly try to bring order out of chaos by nationalizing (or municipalizing) land outright. For in any economy, a useful resource cannot go unowned without chaos setting in; somebody must manage and own — either private individuals or the government. |

In the Georgist proposal, land never goes unowned. The landholders transfer

titles privately, just as they do now, and tax obligations transfer

with the title, just as they do now. All that is necessary is security

of tenure not private appropriation of socially created rent. |

|

George himself expected that the single tax would "accomplish the same thing (as land nationalization) in a simpler, easier, and quieter way."3 The hollow form of private ownership in land would remain, but the substance would have been drained away. |

This is dishonestly quoting George out of context. "The same thing" was the title of the chapter, asserting equal rights to land. George opposed nationalization for exactly the reasons Rothbard complains of, so, in that regard, it's not "the same thing" at all. Unfortunately, Rothbard found his cherry-picked quote and either did not bother to read the very next paragraph, or read it and deliberately lied. We can charitably assume the former, but it's a dishonest quote none the less. Here is the next paragraph:

|

|

Government ownership of land would end one particular form of utter chaos brought about by the single tax, but it would add other great problems. It would raise all the problems created by any government ownership, and on a very large scale.4 In short, there would be no incentive for government officials to allocate sites efficiently, and land would be allocated on the basis of politics and favoritism. Efficient allocation also would be impossible, due to the inherent defects of government operation; the absence of a profit and loss test, the conscription of initial capital, the coercion of revenue — the calculational chaos that government ownership and invasion of the free market create. Since land must be used in every productive activity, this chaos would permeate the entire economy. Socialization as a remedy for the evils of the single tax would be a jump from the frying pan into the fire. |

This is more of Rothbard thinking he is disagreeing with George because he fundamentally fails to comprehend

what George proposed in the first place. George opposed land nationalization for exactly the reasons Rothbard is giving. |

|

Thus we see that private site owners, by allocating sites to productive uses, perform an extremely important service to all members of society. It is a service we would not do without, and the income to owners is but their return for this service. |

Again,

accepting the highest bid is not much of a

service, and would both continue and improve under a land value tax. It

is the land users, not the land owners who allocate sites to productive

uses. |

|

The view that the site owner is nonproductive is a hangover from the old Smith-Ricardo doctrine that "productive" labor must be employed on material objects. The site owner does not solely transform matter into a more useful shape, as the builder does, though he may do that in addition. Lawyers and musicians provide intangible services, just as site owners perform a truly vital function although it may not be a directly physical one. |

This is Rothbard pushing the facile Austrian presumption that people will always do the most profitable thing, when simple observation shows that those who have more wealth than they need most often do the laziest, most convenient thing. Thomas Jefferson observed this in France, noting,

Even today, when we see grossly underused land in prime locations, we find that the owners are not too poor to put the land to good use, but, rather, that they hold so much land that they cannot effectively manage it all. Lawyers and musicians do not hold state titles that

allow them to collect money for merely granting permission to use

something they did not create. |

|

What about the maligned speculator, the holder of idle land? He, too, performs an important service — a subdivision of the general site-owner function. The speculator allocates sites over time. Even if a speculator reaps an "unearned increment" of capital value by holding land as its price rises, he can gain no such increment by keeping land idle. Why shouldn't he use the land and earn rents in addition to his capital gain? Idle land by itself cannot benefit him. The reason he keeps the land apparently idle, therefore, is either that the land is still too poor to be used by current labor and capital goods, or that it is not yet clear which use for the site is best. The "speculative" landowner has the difficult job of deciding when to commit the site to a specific use. A wrong decision would waste the land. By waiting and judging, the speculative landowner picks the right moment for bringing his land into use, and the right employment for the land. Land speculators, therefore, perform as vital a market function as their fellow site owners whose land is already in use. Land that seems idle to a passer-by probably is not idle in the eyes of its owner who is responsible for its use. |

Here again, Rothbard conflates land with improvements

and the land owner with the

land user. It is not the land

that is wasted by being put to use, but the improvements if those

improvements are relatively permanent and become unsuitable. The land

itself his here to be used, and is wasted by not being used. Let us

take the example of a proposed major airport that will be completed in ten years

in an area that is now farmland. Yes, the price of the land would

increase under the current system, but that price is based on

anticipated future

rents. The

actual rental value would not increase until the airport is near

completion and people undertake to build warehouses and hotels near it.

Thus, the market use of the land for the first several years after this

airport is proposed is to continue farming it, and the rent would

remain low accordingly. As Georgists would

assess and tax rental value rather than selling price, the farmer would

not see an increase until people start acquiring land to build hotels,

and they would not want to acquire the land until they were ready to

build. When it is time to start building, that the buildings

might be finished when the airport is finished, the potential land users will offer higher rents for

suitable plots, and the land owners,

whether private citizens or governments, will simply

accept the highest bids. Thus, it is the users, not the owners, who have "the

difficult job of deciding when to commit the site to

a specific use," and it is the capital, not the land itself, that is at

risk. The landowner doesn't care what the capitalist does with that

land, for he gets his payment either way. If, for example, someone

builds a warehouse where a hotel should be, or vice versa, it is his

capital, not the land, that becomes unprofitable. If the solution

is to tear down the warehouse and build a hotel the cost of the original

bad decision was borne by the user. It is these users, the actual

capitalists, who take the risks. And what, we may ask, is this idle landholder actually

waiting for? Obviously he is waiting for higher land prices, but where do

those higher land prices come from? They come from everyone around his

parcel improving their land

before he improves his. Thus,

the most profitable thing for the landholder to do where land is undertaxed is hold out for others to act while

they hold out for him to act. This leads to a standoff and

an artificial shortage of available land, meaning higher land prices

for the improvers and ultimately, meaning unemployed poor with no

access to land. |

|

"Socialization as a remedy for the evils of the single tax would be a jump from the frying pan into the fire." |

Socializing or nationalizing land would indeed be a

terrible answer to the single-tax problems Rothbard describes,

especially since those problems are imaginary. That's why the leading

Marxists, such as H. L. Hyndmann, Marx's #2 man (after Engels),

attacked George's proposals for doing the opposite of what Rothbard

claims they will do:

|

|

We have seen that the economic arguments for the single tax are fallacious at every important turn, and that the economic effects of a single tax would be disastrous indeed. But we should not neglect the moral arguments. Undoubtedly, the passion and fervor that have marked the single taxers through the years stems from their moral belief in the injustice of private ownership of land. Anyone who holds this belief will not be fully satisfied with explanations of the economic error and dangers of the single tax. He will continue to call for battle against what he believes to be a moral injustice. |

We have seen that Rothbard's interpretations are fallacious at every turn, and now we see his misrepresenting the moral arguments as coming from Georgists, when they in fact came from the classical liberals and, long before that, from the Judeo-Christian tradition. What does Rothbard think Jesus's point was in saying, "The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head."? (Matthew, 8:20, Luke 9:58) What of the claim by Moses that God told him "The land shall not be sold for ever: for the land is Mine; for ye are strangers and sojourners with me"? (Leviticus 25:23) What of the curses given for violating this rule? Are they not exactly what happens when land is monopolized? You will build a house, but you will not live in it. You will plant a vineyard, but you will not even begin to enjoy its fruit....A people that you do not know will eat what your land and labor produce, and you will have nothing but cruel oppression all your days. (Deuteronomy 28: 15, 30, 33, Isaiah 5:8, Micah 2:1-3) Or, if you don't like Christianity, what about Lao Tsu? Their courtyards and buildings shall be well kept, but their fields shall be ill-cultivated, and their granaries very empty. They shall wear elegant and ornamented robes, carry a sharp sword at their girdle, pamper themselves in eating and drinking, and have a superabundance of property and wealth; - such princes may be called robbers and boasters. This is contrary to the Tao surely! (Tao Te Ching 53.3, James Legge translation) Or Aristotle? Not only was the constitution at this time oligarchical in every respect, but the poorer classes, men, women, and children, were the serfs of the rich. They were known as Pelatae [dependents] and also as Hectemori [sixth partners], because they cultivated the lands of the rich at the rent thus indicated. The whole country was in the hands of a few persons, and if the tenants failed to pay their rent they were liable to be haled into slavery, and their children with them. All loans secured upon the debtor's person, a custom which prevailed until the time of Solon, who was the first to appear as the champion of the people. But the hardest and bitterest part of the constitution in the eyes of the masses was their state of serfdom. (The Athenian Constitution, part 2) [I]n other states, so far from the democratic parties making advances from their own possessions, they are rather in the habit of making a general redistribution of the land.(ibid, part 40) What of the Lockean Proviso that the right to hold land only exists when there is "enough, and as good, left to others"? What of Locke's strong endorsement of land value tax?

What of Adam Smith's recognition that the price of land is "naturally a monopoly price" or his advocacy of a land value tax based on the morality of government taking the values it has created? What of virtually every

libertarian opposing absolute property ni land prior to the right-wing shift under Hayek, Rothbard Rand

and Mises? |

|

The single taxers complain that site owners benefit unjustly by the rise and development of civilization. As population grows and the economy advances, site owners reap the benefit through a rise in land values. Is it justice for site owners who contribute little or nothing to this advance, to reap such handsome rewards? |

This was a standard complaint of moralists and other

philosophers long before there were single taxers. |

|

All of us reap the benefits of the social division of labor, and the capital invested by our ancestors. We all gain from an expanding market — and the landlord is no exception. The landowner is not the only one who gains an "unearned increment" from these changes. All of us do. Is he, or are we, to be confiscated and taxed out of this happiness in the fruits of advancement? Who in "fairness" could receive the loot? Certainly it could not be given to our dead ancestors, who became our benefactors by investing in capital.5 |

The "the social division of labor, and the capital invested by our ancestors" have nothing to do with the unearned increment in land, for land, labor and capital are three distinct factors of production. That is, land is neither labor nor capital. And while labor and capital profit from producing wealth that benefits all, the landholder profits by arrogating to himself the land others must use and getting paid to let go of it. That is, he benefits at the expense of others. That is the very definition of "unearned increment."

|

|

As the supply of capital goods increases, land and labor become more scarce in relation to them, and therefore more productive. The incomes both of laborers and landowners increase as civilization expands. As a matter of fact, the landowner does not reap as much reward as the laborer from a progressing economy. For landowning is a business like any other, the return from which is regulated and minimized, in the long run, by competition. If land temporarily offers a higher rate of return, more people invest in it, thereby driving up its market price, or capital value, until the annual rate of return falls to the level of all other lines of business. The man who buys a site in mid-Manhattan now will earn no more than in any other business. He will only earn more if the market has not fully discounted future increases in rent through increasing the capital value of the land. In other words, he can only earn more if he can pick up a bargain. And he can only do this if, like other successful profit-makers, his foresight is better than that of his fellows. |

This is false. As the supply of capital goods increases,

land becomes more scarce, but labor becomes more plentiful. It is an

historical fact that the share of wealth given to labor has

continuously fallen while the share given to land has continuously

risen. The only exceptions to this are the discovery of the New World,

which increased available land, and the development of the automobile,

which threw vast tracts of cheap suburban land open to the suburban

worker. However, that benefit gradually disappeared as land speculators

shifted from monopolizing urban land to monopolizing the countryside.

We are talking about the morality of landholding here, and Rothbard's

apologia applies no more to the ownership of land than to the ownership

of slaves. Indeed, we can substitute "slave" for "land" in his

statement and get exactly the same argument in support of slavery: As a matter of fact, the slaveowner does not reap as much reward as the laborer from a progressing economy. For slaveowning is a business like any other, the return from which is regulated and minimized, in the long run, by competition. If a slave temporarily offers a higher rate of return, more people invest in slaves, thereby driving up their market price, or capital value, until the annual rate of return falls to the level of all other lines of business. The man who buys a slave in mid-Manhattan now will earn no more than in any other business. He will only earn more if the market has not fully discounted future increases in slaves through increasing the capital value of the slaves. In other words, he can only earn more if he can pick up a bargain. And he can only do this if, like other successful profit-makers, his foresight is better than that of his fellows. Lest anyone argue that land monopoly and slave ownership are two very different things,

Henry George dedicated chapter 15 of Social Problems, "Slavery and Slavery," to showing the parallels between land monopoly and slavery, but he was hardly the first to see those parallels. |

|

Thus, the only landowners who reap special gains from progress are the ones more farsighted than their fellows — the ones who earn more than the usual rate of return by accurately predicting future developments. Is it bad for the rest of us, or is it good, that sites go into the hands of those men with the most foresight and knowledge of that site? |

This is a clever sleight of hand. "Special gains" for

not producing means gains in excess of what other landholders get for

not producing. It makes no more sense than saying that the only

burglars who are successful are the ones "with the most foresight and

knowledge" of how to burgle. Whether or not that is true has no bearing

on whether burglary is moral. Land still gives a return to

non-producers, and paying to get someone else's privilege has no

bearing on whether it is a privilege. |

|

Among the specially farsighted is the original pioneer — the man who first found a new site and acquired ownership. Furthermore, in the act of clearing the site, fencing it, and the like, the pioneer inextricably mixes his labor with the original land. Confiscation of land would not only retroactively rob heroic men who cleared the wilderness; it would completely discourage any future pioneering efforts. Why should anyone find new sites and bring them into use when the gain will be confiscated? And how moral is this confiscation? |

Rothbard's appeal to land titles through pioneering is delusional, not only because less than 2% of the land titles in the US (and none in Europe) originated with pioneers, not only because pioneers profited by taking up far more land than they could actually use, not only because they robbed natives of access to that land, not only because funding government services from land rent would have attracted others far more quickly, with each taking only what he needed, and not only because no decent land can be acquired that way today, but because there is no logical and moral basis under which the arbitrary and temporary ritual of homesteading confers an absolute and permanent title. There are, in fact, no examples in history of anarchic societies in which absolute and permanent titles were upheld without reciprocal obligations. In the common-law societies, holders of the best land were expected to maintain the greatest lengths of roadway, to offer the greatest provisions to militias, and so on. Among the potlatching tribes of the Pacific Northwest, those tribes with the best land threw lavish parties and gave gifts to neighbors who were relegated to poorer land. As Jefferson observed, Indians of the Northeast only had conditional tenure in improved land, and that tenure disappeared when the improvements disappeared. "A right of property in moveable things is admitted before the establishment of government. A separate property in lands, not till after that establishment. The right to moveables is acknowledged by all the hordes of Indians surrounding us. Yet by no one of them has a separate property in lands been yielded to individuals. He who plants a field keeps possession till he has gathered the produce, after which one has as good a right as another to occupy it. Government must be established and laws provided, before lands can be separately appropriated, and their owner protected in his possession. Till then, the property is in the body of the nation, and they, or their chief as trustee, must grant them to individuals, and determine the conditions of the grant." (Thomas Jefferson: Batture at New Orleans, 1812. ME 18:45) Mark Twain had fun ridiculing this property-by-homesteading superstition so popular with Rothbardians:

|

|

We have still to deal with the critical core of single-tax moral theory — that no individual has the right to own value in land. Single taxers agree with libertarians that every individual has the natural right to own himself and the property he creates, and to transmit it to his heirs and assigns. They part company with libertarians in challenging the individual's right to claim property in original, God-given, land. Since it is God-given, they say, the land should belong to society as a whole, and each individual should have an equal right to its use. They say, therefore, that appropriation of any land by an individual is immoral. |

That isn't horribly wrong, which makes it perhaps the least-wrong paragraph in the entire essay. Georgists do believe that each individual should have an equal right of access to land, but do not believe that it "should belong to society as a whole." This is Rothbard's failure to distinguish the classical-liberal concept of "common rights" from the Marxist concept of "collective rights." I make the difference clear in the article, "Common Rights vs. Collective Rights." Were society as an institution the rightful owner of the land, then the land titles, 98% of which originated as grants from society's government, would be as valid as Rothbard claims them to be. We deny that the earth is the property of society any more than a sporting event is the property of the referees. Just as the job of the referee is to give every competitor an equal chance to play the game, so is the job of society to give every person access to land on equal terms. Rothbard's failure to see any option between private and collective ownership lies at the root of his confusion, which he expands upon in his next paragraph. Finally, Georgists do not say "that appropriation of any

land by an individual is immoral." Rather, it is monopolization of land

ono is not using, in order to prevent others from appropriating land,

that is immoral. The right of each individual to appropriate land on equal terms with others is what Georgists champion. |

|

We can accept the premise that land is God-given, but we cannot therefore infer that it is given to society; it is given for the use of individual persons. Talents, health, beauty may all be said to be God-given, but obviously they are properties of individuals, not of society. Society cannot own anything. There is no entity called society; there are only interacting individuals. Ownership of property means control over use and the reaping of rewards from that use. When the State owns, or virtually owns, property, in no sense is society the owner. The government officials are the true owners, whatever the legal fiction adopted. Public ownership is only a fiction; actually, when the government owns anything, the mass of the public are in no sense owners. You or I cannot sell our "shares" in TVA, for example. |

First of all, the TVA is collective or state property,

not common property. This is another illustration of Rothbard's failure

to distinguish the two. The Georgist position is that land is indeed "given for

the use of

individual persons." It only differs from "talents, health [and]

beauty" in that God or Nature gives these attributes directly to each

individual, whereas the title to land originates with the State. The legitimacy of the land titles Rothbard upholds depends

upon the legitimacy of the State. Albert Jay Nock made it clear in Our

Enemy, the State that what Rothbard defended here is

"the State system of land tenure."

The

irony, then, is that Rothbard is denouncing what he imagines to be

state intervention over land tenure in order to defend what is, in

fact, state intervention over land tenure. |

|

Any attempt by society to exercise the function of land ownership would mean land nationalization. Nationalization would not eliminate ownership by individuals; it would simply transfer this ownership from producers to bureaucrats. |

Again, Rothbard is confused, not only by the difference

between common rights and collective rights, but between landlords and

producers. The landlord, as a landlord, is not a producer, but merely a

rent taker. The land user will get access to land on

better terms, plus the removal of all taxes on use. |

|

Neither can any scheme exist where every individual will have "equal access" to the use of land. How could this possibly happen? How can a man in Timbuktu have as equal access as a New Yorker to Broadway and 42nd Street? The only way such equality could be enforced is for no one to use any land at all. But this would mean the end of the human race. The only type of equal access, or equal right to land, that makes any sense is precisely the equal access through private ownership and control on the free market — where every man can buy land at the market price. |

Now Rothbard is being ridiculously obtuse. The point is

not to give everyone equal access to each

plot of land, but to give everyone an equal right of access to land generally within a governing

jurisdiction. Can New Yorkers not have equality within New York until

the people of Timbuktu have equality within Timbuktu? Were we wrong to

abolish slavery in the United States because there was still slavery

for more than another hundred years in Timbuktu? What if there might be

intelligent life on Mars? Can we not have equality on earth if there might still be inequality butween us and to Martians? Rothbard again shows his ignorance by saying that nobody could use land at all, when the only land that cannot be used at all is the land held idle under the system he defends. Everyone having a right of access to land generally obviously does not mean everyone having an equal right to each parcel of land. Such desperate objections are a sign of ideological possession. "Equal access through private ownership and

control on the free market" is exactly what Georgists classical

liberals and most paleolibertarians advocated. They saw land value

tax as essential to that. |

|

"Man comes into the world with just himself and the world around him — with the land and natural resources given him by nature. He takes these resources and transforms them by his labor and energy into goods more useful to man." |

Yes, that's the Georgist (and paleolibertarian)

perspective, but he no longer has "land and natural resources given him

by nature" if those resources have been monopolized by others. When he "transforms

them by his labor and energy" it's the value of those improvments that

become property, but the land itself is given to all individuals.

Rothbard is happy that "The Lord giveth and the landlord taketh away." |

|

The single taxer might still claim that individual ownership is immoral, even if he can find no plausible remedy. But he would be wrong. For his claim is self-contradictory. A man cannot produce anything without the cooperation of original land, if only as standing room. A man cannot produce anything by his labor alone. He must mix his labor with original land, as standing room and as raw materials to be transformed into more valuable products. |

If Rothbard were serious, he would find out what

single-taxers do say instead

of speculating on that they might

say. Georgists have no problem with secure tenure in land if it does

not impinge on the rights of others. Meanwhile, it is only right-wing

neolibertarians who have found "no plausible remedy," even failing to

see the remedies handed down by the libertarians who came before them.

One only has to search for the word "Land" in Liberty and the Great Libertarians

to see copious examples of libertarians disagreeing with Rothbard here

and offering plausible remedies. If a "man cannot produce anything by

his labor alone, but must mix his

labor with original land" in order to survive, then how is a landless

person free when all the decent land is monopolized, and much of it is

held out of use? What of his

individual rights? |

|

Man comes into the world with just himself and the world around him — with the land and natural resources given him by nature. He takes these resources and transforms them by his labor and energy into goods more useful to man. Therefore, if an individual cannot own original land, neither can he in the same sense own the fruits of his labor. The single taxers cannot have their cake and eat it; they cannot permit a man to own the fruits of his labor while denying him ownership of the original materials which he uses and transforms. It is either one or the other. To own his product, a man must also own the material which was originally God-given, and now has been remolded by him. Now that his labor has been inextricably mixed with land, he cannot be deprived of one without being deprived of the other. |

This is a classic case of projection. Rothbard says man comes into this world "with the land and natural resources

given him by nature," while defending those who demand payment by that man for what nature has

given to that man. He

imagines that, without state-issued land titles, man cannot "own

the fruits of his labor." How, then, did man own the fruits of his labor for

the millions of years before there were land titles? How, then, does a landless person own the

fruits of his labor today? The Rothbardian

apologists for monopoly cannot have their cake and eat it. They cannot

permit monopolists to deny others access to land and then prate about

those others having the fruits of their labor. |

|

But if a producer is not entitled to the fruits of his labor, who is entitled to them? It is difficult to see why a newborn Pakistani baby should have a moral claim to ownership of a piece of Iowa land someone has just transformed into a wheat field. Property in its original state is unused and unowned. The single taxers may claim that the whole world really "owns" it, but if no one has yet used it, it is really owned by no one. The pioneer, the first user of this land, is the man who first brings this simple valueless thing into production and social use. It is difficult to see the morality of depriving him of ownership in favor of people who never got within a thousand miles of the land, and whose only claim to its title is the simple fact of being born — who may not even know of the existence of the property over which they are supposed to have claim. |

Rothbard once again conflates land rent with the fruits of labor, as if the Iowa landlord created the Iowa land, and he again fails to notice that the fruits of the tenant's labor is taken by the landlord. He again fails to grasp that the additional value the landholder created when he "transformed [that land] into a wheat field" is an improvement and would not be taxed. He also talks about a "Pakistani baby having a moral claim to ownership of a piece of Iowa," further demonstrating that he failed to grasp the the difference between common rights to land generally and collective ownership of each parcel, and the difference between creating equal rights within a country and some kind of world domination scheme. Let the parents of this Pakistani baby bring him to an Iowa that has the single tax in place, and that baby will grow up with access to land on the same terms as anyone else living in Iowa. But, as Rothbard has no sound arguments against actual

Georgist proposals, he has to make up straw-man proposals to knock down. |

|

Surely, the moral course is to grant ownership of land to the person who had the enterprise to bring it into use, the one who made the land productive. The moral issue will be even clearer if we consider the case of animals. Animals are "economic land" — since they are original nature-given resources. Yet will anyone deny full title to a horse to the man who finds and domesticates it? Or should every person in the world put in his claim to one two-billionth of the horse — or to one two-billionth of a government assessor's estimate of the "original horse's" worth? Yet this is precisely the single taxer's ethic. In all cases of land, some man takes previously undomesticated, "wild" land, and "tames" it by putting it to productive use. Mixing his labor with land sites should give him just as clear a title as in the case of animals. |

This is another straw-man, or perhaps a straw-horse. Georgists are adherents of the Lockean Proviso, that it is acceptable to hold land or anything else found in nature so long as there is "enough and as good left to others." As horses were not scarce, there was no reason to prevent them from being privately appropriated. An endangered species would be a substantially different matter. Rothbard's essential flaw is his failure to see that you

don't pay taxes to use land, but to create an artificial shortage of

land and thereby exclude others from using land. Yes, if wild horses

were deemed to be scarce, there could well have been a charge for

taking horses from the commons and a limit on how many one may take -

just as there is a charge for fishing licenses and limits on how many

fish one may catch. The American system of licenses and limits equally available to all is entirely

consistent with Georgist principles, while the aristocratic system used

in England is consistent with Rothbardian principles. Under that

system, landlords had unlimited rights to take game from the forests,

and ordinary Englanders had no rights at all. |

|

As two eminent French economists

have written, Nature has been appropriated by him (man) for his use; she has become his own; she is his property. This property is legitimate; it constitutes a right as sacred for man as is the free exercise of his faculties. Before him, there was scarcely anything but matter; since him, and by him, there is interchangeable wealth. The producer has left a fragment of his own person in the things which … may hence be regarded as a prolongation of the faculties of man acting upon external nature. As a free being he belongs to himself; that is to say the productive force, is himself; now, the cause, that is to say, the wealth produced, is still himself. Who shall dare contest title of ownership so clearly marked by the seal of his personality?6 |

I had not heard of these "eminent" economists, and I expect they are not nearly as eminent as the French Physiocrats, who coined the terms "laissez faire" and "impôt unique," (i.e., "single tax" on land), and who campaigned to get other taxes replaced by land value tax, or as the ten Nobel Laureates in Economics who have explicitly advocated land value tax. In

any case, these "eminent" economists have not

explained, if the right to appropriate land is "as sacred for man as is

the free

exercise of his faculties," why some people have the right to deny

other people's sacred rights of access to land. It seems to me (and to

Locke) that

there must be a limit to that right, and the most logical limit is the

point where it denies others of the right to do the same, especially

when one is not even using the land in question. At least these two

economists denied property from mere occupancy, and argued that there

must be improvements. How one can justly hold property in land by using it and

also by not using it is too Zen for the rational mind, and even for the economists he is citing, but apparently

not for Zen Master Rothbard.

|

|

1. Phil Grant The Wonderful Wealth Machine (New York: Devin-Adair, 1953), pp. 105–7. |

A PDF of the book is online here, courtesy of the Henry George School of Social Sciences, NYC. |

|

2. Unfortunately, most economists have accepted this claim uncritically and only dispute the practicality of the single-tax program. |

The claim that land value tax does not restrict

production has been examined and thorougly tested, going all the way

back to Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill. Rothbard is displaying his

ignorance on the subject. |

|

3. Henry George, Progress and Poverty (New York: Modern Library, 1916), p. 404. |

|

|

4. For a further discussion of these problems, see the author's "Government in Business," The Freeman (September 1956) 39–41. |

|

|

5. "'What gives value to land?,' asks Rev. Hugh O. Pentecost. And he answers: 'The presence of population — the community. Then rent, or the value of land, morally belongs to the community.' What gives value to Mr. Pentecost's preaching? The presence of population — salary, or the value of his preaching, morally belongs to the community." Benjamin R. Tucker, Instead of a Book (New York: B.R. Tucker, 1893), p. 357. Also see Leonard E. Read, "Unearned Riches," in On Freedom and Free Enterprise, Mary Sennholz, ed. (Princeton: D. Van Nostrand, 1956), pp. 188–95; and F.A. Harper, "The Greatest Economic Charity," in ibid., pp. 94–108. |

Like Rothbard, Tucker's hatred of government was

stronger than his love of liberty, and it led him to illogical

justifications. It should be obvious to anyone that "the presence of

population" is not enough to give value to a lecturer's preaching. If

the preaching itself is not of sufficient quality to inspire people to

pay to see the preaching or to donate to the preacher, then the

preaching has no value whatsoever. Moreover, no state title denies

anyone access to preaching just because somone else wants to preach,

unless they are denied access to the location because someone else has

paid to be there. At least Tucker didn't grant permanent property on the

assertion of first use or first occupancy, but only on continued use.

Property that fell out of use was considered to be abandoned. In this

regard, Tucker is more rational than Rothbard. |

|

6. Leon Wolowski and Emilet Levasseur, 'Property" in Labor's Cyclopedia of Political Science (Chicago: M.B. Cary, 1884), p. 392. |

Note that these economists did not defend property based on occupancy, but only based on improvements. This undermines Rothbard's argument for property in land held idle. Also, in their section, "Of the Objections to Property," they only cite the objections of communists and socialists. Conspicuously absent are the objections of John Locke, François Quesnay, Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Adam Smith, Tom Paine, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill, all of whom wrote prior to 1864, the estimated original date of this work. One might make the distinction that many of these people

did not oppose property in land outright, but just proposed putting the

burden of taxation on land values. However, that distinction was lost on Rothbard. |

We are interested in comments that generate more light than heat:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263