Case of the SouthChapter 3

|

Saving Communities

|

|||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

Get Involved |

The Case of

the South Against the

North

The Case of

the South Against the

North

Or

Historical Evidence Justifying the Southern States of the American

Union in their Long Controversy with the Northern States

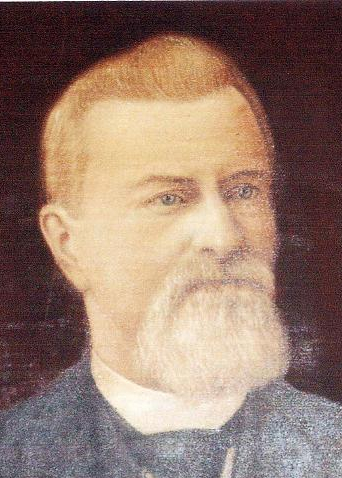

Benjamin

Franklin Grady,

A Representative in the Fifty-Second and Fifty-Third Congresses of

the United States

EDWARDS & BROUGHTON, PUBLISHERS,

RALEIGH, N. C., 1899

CHAPTER IV.

"ONE PEOPLE."

Familiar as we now are with the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution, we are prepared for an intelligent discussion of the unwarranted and vicious doctrines which some seventy years ago began to supplant in some sections of the Union the true principles of the Federal Government. And strangely enough the first effective impulse given to them was in the States which theretofore had been the most consistent and strenuous supporters of the sovereignty, freedom and independence of the several States.

It was in New England; and it is one of the curious coincidences of history that her intellectual forces began to organize for the denial of the teachings of their fathers about the time there was a consolidation of sentiment in the Southern States against the injustice of protection to New England's manufacturers, leading in one State to the adoption of measures threatening the peace of the Union.

The substance of their new doctrines was that the people of the several States had consolidated themselves into a sovereign Nation, and that the people of one State bear about the same relation to the Nation that those of a county bear to their State.

The two most brilliant luminaries (of whom the lesser lights became as mere reflections) who championed this doctrine, were Joseph Story and Daniel Webster.

The celebrated speech of the latter, delivered in the Senate on the 16th of February, 1833, and the former's Commentaries on the Constitution, published the same year, became the accepted exposition of the Constitutional relations of the States in their section of the Union. Mr. Webster's speech was kept before the youth of the country in school readers, speakers, political addresses, etc.; and Judge Story's Commentaries, adopted as a text-book in many seminaries of learning, even in the Southern States, polluted the fountains of political truth in all sections.

The "one people" doctrine, founded by both of them on substantially the same basis, may be conveniently summarized as follows:

1. "None of the Colonies before the Revolution were, in the most large and general sense, independent, or sovereign communities. They were... subjected to the British Crown. Their powers and authorities were derived from, and limited by their respective charters.... They could make no treaty, declare no war, send no ambassadors, regulate no intercourse or commerce, nor in any other shape act as sovereigns in the negotiations usual between independent States. In respect to each other, they stood in the common relation of British subjects.... If in any sense they might claim the attributes of sovereignty, it was only in that subordinate sense, to which we have alluded, as exercising within a limited extent certain usual powers of sovereignty. They did not even affect local allegiance.

2. "The Colonies did not severally act for themselves, and proclaim their independence. It is true that some of the States had previously formed incipient governments for themselves; but it was done in compliance with the recommendations of Congress. Virginia, on the 29th of June, 1776, by a convention of Delegates, declared 'the Government of this Country,1 as formerly exercised under the Crown of Great Britain, totally dissolved'; and proceeded to form a new Constitution, of Government. New Hampshire also formed a Government in December, 1775, which was manifestly intended to be temporary, 'during,' as they said, 'the unhappy and unnatural contest with Great Britain.' New Jersey, too, established a frame of Government, on the 2d of July, 1776; but it was expressly declared that it should be void upon a reconciliation with Great Britain. And South Carolina, in March, 1776, adopted a Constitution of Government; but this was, in like manner, 'established until an accommodation between Great Britain and America could be obtained.'

3. "The Declaration of Independence of all the Colonies was the united act of all. It was 'a Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled'; 'by the delegates appointed by the Good People of the Colonies,' as in a prior Declaration of Rights they were called. It was not an act done by the State Governments, then organized; nor by persons chosen by them. It was, emphatically, the act of the whole People of the United Colonies, by the instrumentality of their Representatives, chosen for that, among other purposes. It was an act, not competent to the State Governments, or any of them, as organized under their Charters, to adopt. Those Charters neither contemplated the case, nor provided for it. It was an act of original, inherent Sovereignty, by the People themselves, resulting from their right to change the form of Government, and to institute a new Government whenever necessary for their safety and happiness. So the Declaration of Independence treats it. No State had presumed, of itself, to form a new Government, or to provide for the exigencies of the times, without consulting Congress on the subject; and when they acted, it was in pursuance of the recommendation of Congress.

It was, therefore, the achievement of the whole for the benefit of the whole.... The Declaration of Independence has, accordingly, always been treated as an act of Paramount and Sovereign authority, complete and perfect, per se.

4. "The separate Independence and individual Sovereignty of the several States were never thought of by the enlightened band of patriots who framed this Declaration. The several States are not even mentioned by name in any part of it, as if it was intended to impress the maxim on America, that our freedom and independence arose from our Union, etc.

5. "We have seen that the power to do this act - declare Independence - was not derived from the State Governments; nor was it done generally with their cooperation. The question, then, naturally presents itself, if it is to be considered as a National act, in what manner did the Colonies become a Nation, and in what manner did Congress become possessed of this National power? The true answer must be that as soon as Congress assumed powers, and passed measures, which were, in their nature, National, to that extent, the People, from whose acquiescense and consent they took effect, must be considered as agreeing to form a Nation."2

6. "The Constitution is not a league, confederacy, or compact between the people of the several States in their sovereign capacities; but in the ratifying ordinances of Massachusetts and New Hampshire the truth is recognized that the people of the United States 'entered into an explicit and solemn compact with each other.' It is the People, and not the States, who have entered into the compact; and it is the People of all the United States... a social compact. No man can get over the words, 'We, the People of the United States, do ordain and establish this Constitution.' These words must cease to be a part of the Constitution... before any human ingenuity or human argument can remove the popular basis on which that Constitution rests, and turn the instrument into a mere compact between sovereign States.... The Constitution, Sir, regards itself as perpetual and immortal. It seeks to establish a Union among the people of the States," etc. - Mr. Webster's speech in the Senate, February 16, 1833.

Every claim of these authorities is negatived by the universally accepted definition of the word "State" among English-speaking people before and during our Revolutionary period; but if the reader hesitates to admit that a mere definition can weaken a position assumed by such distinguished statesmen, let us examine the propositions they lay down and the historical evidence on which they rely. We will follow the foregoing order.

1. Nobody ever contended that the Colonies were, in any sense, "independent or Sovereign communities," or that they affected "local allegiance"; and the apparent pretense that such a claim had ever been set up tends, if not so designed, to befog the whole subject.

But it is true that each one of the Colonies, after July 4, 1776, did "affect local allegiance." For example, the Constitution of Massachusetts, adopted in 1780, required every person chosen to an office, whether civil or military, to swear "true faith and allegiance" to the Commonwealth; which oath was not changed when the Constitution was amended in 1822. The same oath was required by New Hampshire in 1792, and was not stricken out of her Constitution in 1852, when it was amended.

2. It would have been suicidal for any one of the Colonies to declare itself independent of Great Britain, or even for half of them to do so. Cooperation was necessary to success. But the contention that the Declaration was the work of the Representatives of "one people" who possessed "original, inherent Sovereignty," while in their separate Colonies temporary governments had been adopted, which were to be abandoned on a reconciliation with the mother Country, is self-destructive. How all the people could be "Sovereign," while those in each Colony were subject to the Crown of Great Britain, their relations being only temporarily suspended, is beyond human comprehension.

The truth about the relations and the actions of the separate Colonies is clearly set forth by Mr. Jefferson in his writings, Volume I, page 10 (copied in Elliot's Debates, Vol. I, pp. 56 et seq.), as follows:

"In Congress, Friday, June 7, 1776. The delegates from Virginia moved, in obedience to instructions from their constituents,3 that the Congress should declare that these United Colonies are, and of right, ought to be free and independent States, etc.

"It was argued by Wilson (Pennsylvania), Robert R. Livingston (New York), E. Rutledge (South Carolina), Dickinson (Delaware), and others,... that the people of the middle Colonies (Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, the Jerseys, and New York) were not yet ripe for bidding adieu to British connection, but that they were fast ripening, etc. That some of them had expressly forbidden their delegates to consent to such a declaration, and others had given no instructions, and consequently no power to give such assent; that, if the delegates of any particular Colony had no power to declare such Colony independent, certain they were, the others could not declare it for them; the Colonies being as yet perfectly independent of each other; that the Assembly of Pennsylvania was now sitting above stairs; their Convention would sit in a few days; the Convention of New York was now sitting; and those of the Jerseys and Delaware counties would meet on Monday following; and it was probable these bodies would take up the question of independence, and would declare to their delegates the voice of their State.

"That, if such a declaration should now be agreed to, these delegates must retire, and possibly their Colonies might secede from the Union...4 It appearing in the course of these debates that the Colonies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and South Carolina5 were not yet matured for falling from the parent stem, but that they were fast advancing to that state, it was thought most prudent to wait a while for them, and to postpone the final decision to July 1; but that this might occasion as little delay as possible, a committee was appointed (June 11) to prepare a Declaration of Independence. The committee were John Adams, Dr. Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston and Thomas Jefferson. Committees were also appointed, at the same time, to prepare a plan of Confederation of the Colonies, and to state the terms proper to be proposed for foreign alliances....

"On Monday, the 1st of July, the House resolved itself into a Committee of the Whole. and resumed the consideration of the original motion made by the delegates of Virginia, which being again debated through the day, was carried in the affirmative by the votes of New Hampshire, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. South Carolina and Pennsylvania6 voted against it. Delaware had but two members present, and they were divided. The delegates from New York declared they were for it themselves, and were assured their constituents were for it; but that their instructions having been drawn near a twelvemonth before, when reconciliation was still the general object, they were enjoined by them to do nothing which should impede that object. They, therefore, thought themselves not justifiable in voting on either side.... Mr. Edward Rutledge, of South Carolina, then requested the determination (in the House) might be put off to the next day, as he believed his colleagues, though they disapproved of the resolution, would then join in it for the sake of unanimity...7 In the meantime, a third member had come post from the Delaware counties, and turned the vote of that Colony.... Members of a different sentiment attending that morning from Pennsylvania also, her vote was changed, etc., so that the whole twelve Colonies, who were authorized to vote at all, gave their voices for it; and within a few days (July 9th) the Convention of New York approved of it, and thus supplied the void occasioned by the withdrawing of her delegates from the vote.

"Congress proceeded the same day to consider the Declaration of Independence."

There seems, therefore, no basis for the assertion that "the Colonies did not severally act for themselves." And as to their having no governments, Jefferson's testimony is decisive.

3. The Declaration of Independence was "an act done by... persons chosen by" "the State Governments"; and the doctrine of "qui facit per alium facit per se," applies here as it does to the responsibility of any other employer.

They were not chosen, it is true, by the Charter Governments - it has never been pretended that they were; they were chosen in each Colony by legislative bodies elected by the people for this and other purposes. In North Carolina, for example, John Harvey, Moderator of the body which had, in 1774, elected Joseph Hewes, William Hooper and Richard Caswell to represent the Colony in the Continental Congress, issued a notice to the people of the Colony, in February, 1775, asking them to elect delegates to represent each town (borough) and county in a Convention. The Convention met in Newbern, April 4, 1775, the same day on which the Colonial Assembly met, many gentlemen being members of both bodies. Governor Josiah Martin soon dissolved the Colonial Assembly, and the Colony never again saw a legislative body meet under the direction of a Royal Governor; the people were thenceforth governed by themselves; and although they had no written Constitution till December, 1776, it would be as absurd to say that they had no Government during this interval as it would to assert the same thing of England; which has never had a written Constitution. On August 21, 1775, another legislative body, composed of 184 members, met in Hillsboro, appointed a Provincial Council for the state, a District Committee for each District, County and Town Committees for each county and town, raised two regiments of 500 men each, emitted $125,000 in bills on the credit of the State, passed an act empowering the Provincial Council to enforce an oath of allegiance on suspects,8 and did every other thing which any government could have done. The next legislative body met at Halifax on the 4th of April, 1776, and among other things it did, it passed unanimously the following resolution: "That the Delegates from this Colony in the Continental Congress be empowered to concur with the delegates from the other Colonies, in declaring Independence and forming foreign alliances; reserving to this Colony the sole and exclusive right of forming a constitution and laws for this Colony."9 -Colonial Records, X, 512.

4. "The several States are not even mentioned by name in any part of" the Declaration for the very reason which caused them to be stricken out of the Constitution after "We, the people"; it was not known by the committee appointed June the 11th to draft the Declaration whether all the Colonies would approve it; and the hope that Canada would ultimately "join in the measures" of the thirteen Colonies rendered it improper to name them and leave her out. This omission is not of the least significance as a support to the "one people" theory, since the right "of these Colonies to alter their former systems (plural) of government" was recognized and demanded in the Declaration - evidently excluding the idea that the Declaration was designed to dethrone George III and enthrone "one people."

As to the claim that "the separate Independence and individual Sovereignty of the several States were never thought of by the enlightened band of patriots who framed this Declaration," its utter want of support is shown by the second Article of the Articles of Confederation framed by a committee appointed by this "enlightened band of patriots," agreed to by them or their successors, and by all the States. It is:

"Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States in Congress assembled."

This was an indisputable recognition of the "Independence and individual Sovereignty" of each State, since it could not "retain" what did not belong to it.

5. There is not a syllable nor a hint anywhere in the Declaration of Independence that it was intended to merge the peoples of thirteen free, sovereign and independent States into a Nation; nor was there any assumption of sovereign powers by the Continental Congress, since the delegation from each Colony was empowered by its Colony to exercise all the powers necessary and proper for the conduct of the war and, foreign intercourse. And in the Articles of Confederation the second Article, quoted above, is so absolutely inconsistent with the theory of the consolidationists, that they hardly deserve a respectful refutation.10

6. The answer to Mr. Webster by Mr. Calhoun, and the complete overthrow of his political doctrine, by quoting his own former utterances (always scrupulously ignored and excluded by Northern compilers of school readers, speakers, Union text-books, etc.), may profitably be imitated here. In June, 1851, Mr. Webster delivered an address at Capon Springs, V a., in which he said:

"I have not hesitated to say, and I repeat, that, if the Northern States refuse, willfully and deliberately, to carry into effect that part of the Constitution which respects the restoration of fugitive slaves, and Congress provide no remedy, the South would no longer be bound to observe the compact. A bargain can not be broken on one side, and still bind the other side."11

Mr. Calhoun's quotations from Mr. Webster's former speeches, and this subsequent utterance at Capon Springs indicate a temporary confusion of thought in 1833, in the midst of the dangers to the Union which protection to New England's manufacturers had caused.

But even if there were no reason to charge Mr. Webster with inconsistency, he is not supported by the evidence he adduces; on the contrary, it is against him. "The people of the United States" in the ratifying ordinances of New Hampshire and Massachusetts, to which he refers, meant the people of the thirteen free, sovereign, independent, and separate States, each State having retained its "sovereignty, freedom and independence" in the Union. Such were "the people of the United States" at that time, and it was a remarkable distortion of the import of the phrase to make it equivalent to "one people" or Nation.12

His appeal to the "We, the people" in the preamble of the Constitution is as unavailing as that to the ordinances of New Hampshire and Massachusetts; it indicates an inexcusably superficial examination of the provisions of the Constitution. Whenever nine States ratified the Constitution, it was to be a "Constitution be-tween" - not for, or of, or among - "the States" - not people - "so ratifying the same."

Even this little preposition "between," which is a compound of the old preposition be, which signifies at, in, or by, and the numeral adjective tween, which signifies twain, twin, or two, not only disposes of the "one people" doctrine; but it clearly demonstrates that the compact was between two parties, each State being one of them and its co-States the other. If this is untrue, the statesmen of 1787 were ignorant of the meaning of between.13

Thus it is beyond question that, if we are guided by the accepted definitions of words, the recognized canons of interpretation of language, and the recorded acts of deliberative bodies, there is not even a shadow of a foundation for the contention that the peoples of the several States were ever consolidated into a Nation, or "one people"; and it is among the marvels of this century that any intelligent man could derive such a doctrine from the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, or the Constitution. And the marvel grows when we find this absurd definition of "State" in all the editions of Webster's Dictionary published since 1864: "In the United States one of the Commonwealths14 or bodies politic, the people of which make up the body of the Nation, and which, under the National Constitution, stand in certain specified relations with the National Government, and are invested, as Commonwealths, with full power in their several spheres, over all matters not expressly inhibited."

1. Note the use of the word "country."

2. Elliot's Debates, Vol. I, pages 163-67.

3. Judge Story and other consolidationists have confused the minds of their readers by irrelevant distinctions between the people of a State and the government of a State. The "constituents" of Jefferson, Lee, etc., were not living in a state of anarchy; they had a government; and whether it was modeled on that of Great Britain or on the pure democracy of Athens, was of no consequence.

Another Massachusetts writer makes a

distinction between the State (the soil, climate, etc.), and its

inhabitants, thus: "The Constitution was not adopted by the State,

but by the people dwelling in the State." - William Sullivan's

Political Class-Book, revised by George B. Emerson (1831).

4. Since the Colonies were "as yet perfectly independent of each other," it is not clear how any one of them could "secede from the Union."

5. "Maryland and South Carolina had joined in the Declaration of Independence without any crying grievances of their own." - Fiske's Critical Period, etc., page 92.

6. In an address to the people of Pennsylvania, James Wilson, one of the delegates from that State, said: "When the measure (the Declaration of Independence) began to be an object of contemplation in Congress, the delegates of Pennsylvania were expressly restricted from consenting to it. My uniform language in Congress was, that I never would vote for it, contrary to my instructions. I went further, and declared that I never would vote for it, without your authority.... When your authority was communicated by the conference of Committees from the several counties of the State. I then stood upon very different grounds: I declared so in Congress. I spoke and voted for the measure."

7. It appears that the delegates from Delaware and South Carolina had no positive instructions, but were permitted to exercise their own judgment in emergencies like this. Those from South Carolina, it is probable, were hurried into harmony by Sir Henry Clinton's invasion of their State. It has been said by respectable authorities that the course of these as well as of other delegates was determined by the repulse (June 28) of Sir Henry's army and Sir Peter Parker's fleet; but it is not probable that news could have gone from Charleston to Philadelphia in six days.

8. Thus "affecting local allegiance" nearly a twelvemonth before the date of the Declaration of Independence. "They" (the committees of the counties), says Wheeler "had a test oath to which all persons had to subscribe, which was paramount to the oath of alle giance to the English Crown.''' - Wheeler, Series I, Chapter IX.

9. This was passed on the 12th of April, 28 days before the Continental Congress advised the Colonies to adopt Constitutions!

10. One of the most glaring non-sequiturs in all the writings of the consolidationists occurs on page 525 of Bancroft's fourth volume, as follows: "On the 24th (June) Congress 'resolved that all persons abiding within any of the united Colonies, and deriving protection from its laws, owe allegiance to the said laws, and are members of such Colony'; and it charged the guilt of treason upon 'all members of any of the united Colonies who should be adherent to the King of Great Britain. giving to him aid and comfort.' The fellow-subjects of one king became fellow-lieges of one republic. They all had one law of citizenship and one law of treason."

11. Curtis's Life of Webster, Volume II, pages 518-519.

13. The consolidationists at an early date (Mr. Webster, e. g., at the laying of the Corner Stone of the Bunker Hill Monument, on June 17, 1825) substituted "over" for "between," and to-day very few people have the courage to deny that the Government is "over" the States.

14. This word "commonwealth" was substituted by the Puritans of England for "kingdom," being the English equivalent for the Latin Respublica; and the change was made because there was a change in the source of political power, the freedom, sovereignty and independence of England not being affected. Thence it was imported into these Colonies in 1776, and adopted by some of them. It was a specific title, while "State" was general; but both, in political nomenclature, implied nothing less than absolute autonomy.

The flag of the United States preserves the truth as to the "one people" doctrine. On June 14, 1777, the Congress which submitted the Articles to the States, passed this resolution: "That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white, with thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation." Afterwards the stars in the "new constellation" were increased as new States were added to the Union, the first act of the Congress presiding for such increase being passed April 4, 1818.

It was a union of separate and sovereign States, bound together by the ties of mutual interest and for mutual defense, the same ties which bound them under the Articles and under the Constitution. Such was the significance of the flag in the beginning, and nothing has happened since to impart any other significance to it. If this is not true, the stars should have been long ago removed from it and the population of the "Nation" substituted for them, the thirteen stripes remaining to remind us of the time when the United States "were."

Comments. We are interested in comments that generate more light than heat. Please avoid grandstanding:

Saving Communities

420 29th St.

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263