The Two Senses of Value

Epigraphs to Book IIDefinitions are the basis of systematic reasoning. — Aristotle The mixture of those things by speech which are by nature divided is the mother of all error. — Hooker Bacon made us sensible of the emptiness of the Aristotelian philosophy; Smith, in like manner, caused us to perceive the fallaciousness of all the previous systems of political economy; but the latter no more raised the superstructure of this science, than the former created logic.... We are, however, not yet in possession of an established text-book on the science of political economy, in which the fruits of an enlarged and accurate observation are referred to general principles that can be admitted by every reflecting mind; a work in which these results are so complete and well arranged as to afford to each other mutual support, and that many everywhere and at all times be studied with advantage. — J.B. Say, 1803 We may cite as examples of such inchoate but yet incomplete discoveries the great Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith — a work which still stands out, and will ever stand out, as that of a pioneer, and the only book on political economy which displays its genius to every kind of intelligent reader. But among the specialists and the schools, this work of genius which swayed all Europe in its day, is laid upon the shelf as an antiquated affair, superseded by the smaller and duller men who have pulled his system to pieces and are offering us the fragments as a science most of whose first principles are still under dispute. — Professor (Greek) J.P. Mahaffy, "The Present Position of Egyptology," "Nineteenth Century," August, 1894. Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works. |

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

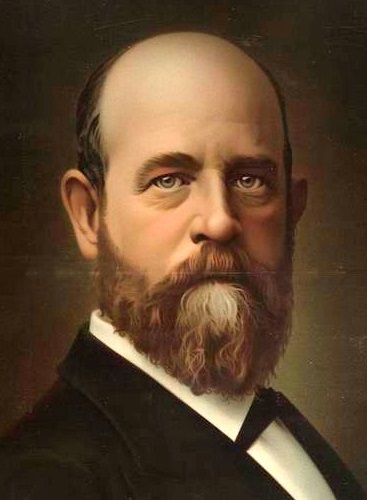

Henry George

|

Importance of the term value — Original meaning of the word — Its two senses — Names for them adopted by Smith — Utility and desirability — Mill's criticism of Smith — Complete ignoring of the distinction by the Austrian school — Cause of this confusion — Capability of use not usefulness — Smith's distinction a real one — The dual use of one word in common speech must be avoided in political economy — Intrinsic value

The term value is of most fundamental importance in political economy; so much so that by some writers political economy has been styled the science of values. Yet in the consideration of the meaning and nature of value we come at once into the very quicksand and fogland of economic discussion — a point which from the time of Adam Smith to the present has been wrapped in increasing confusions and beset with endless controversy. Let us move carefully, even at the cost of what may seem at the moment needless pains, for here is a point from which apparently slight divergences may ultimately distort conclusions as to matters of the utmost practical moment.

The original and widest meaning of the word "value" is that of worth or worthiness, which involves and expresses the idea of esteem or regard.

But we esteem some things for their own qualities or for uses to which they may be directly put, while we esteem other things for what they will bring in exchange. We do not distinguish the kind or reason of regard in our use of the word esteem, nor yet is there any need of doing so in our common use of the word value. The sense in which the word value is used, when not expressed in the associated words or context, is for common purposes sufficiently indicated by the conditions or nature of the thing to which value is attributed. Thus, the one word value has in common English speech two distinct senses. One is that of usefulness or utility — as when we speak of the value of the ocean to man, the value of the compass in navigation, the value of the stethoscope in the diagnosis of disease, the value of the antiseptic treatment in surgery; or when, having in mind the merits of the mental production, its quality of usefulness to the reader or to the public, we speak of the value of a book.

The other and, though derived, utterly distinct sense of the word value, is that of what is usually, and for most purposes even of political economy, sufficiently described as exchangeability or purchasing power — as when we speak of the value of gold as greater than that of iron; of a book in rich binding as being more valuable than the same book in plain binding; of the value of a copyright or a patent; or of the lessening in the value of steel by the Bessemer process, or in that of aluminium by the improvements in extraction now going on.

The first sense of the word value, which is that of usefulness, the quality that a thing may have of ministering directly to human needs, was distinguished by Adam Smith as "value in use."

The second sense of the word value, which is that of worth in transfer or trade, the quality that a thing may have of ministering indirectly to human desire through its exchangeability for other things, was distinguished by Adam Smith as "value in exchange."

Adam Smith's words are (Book I, Chapter IV):

The word "value," it is to be observed, has two different meanings, and sometimes expresses the utility of some particular object, and sometimes the power of purchasing other goods which the possession of that object conveys. The one may be called "value in use;" the other, "value in exchange." The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water; but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use, but a very great quantity of goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.

These two terms, adopted by Adam Smith, as best expressing the two distinct senses of the word value, at once took their place in the accepted economic terminology, and have since his time been generally used.

But though the terms of distinction which he used have been from the first accepted, this has not been the case with the distinction itself. From the first, his successors and commentators began to question its validity, declaring that nothing could have exchange value for which there was not demand; that demand implied some kind of utility or usefulness, and hence that what has value in exchange must also have value in use; and that Smith had been led into confusion by a disposition to import moral distinctions into a science that knows nothing of moral distinctions. This view has been generally, so far indeed as I know universally, accepted by political economists.*

Thus, John Stuart Mill (whom I take as the best exponent of the scholastically accepted political economy up to the time when the Austrian or psychological school began to become the "fad" of confused professors), begins his treatment of value by pointing out that "the smallest error on that subject infects with corresponding error all our other conclusions, and anything vague or misty in our conceptions of it creates confusion and uncertainty in everything else." And he thus proceeds (Principles of Political Economy, Book III, Chapter I, Sec. I)

We must begin by settling our phraseology. Adam Smith, in a passage often quoted, has touched upon the most obvious ambiguity of the word "value;" which, in one of its senses, signifies usefulness, in another, power of purchasing; in his own language, value in use and value in exchange. But (as Mr. De Quincey has remarked) in illustrating this double meaning, Adam Smith has himself fallen into another ambiguity. Things (he says) which have the greatest value in use have often little or no value in exchange; which is true, since that which can be obtained without labor or sacrifice will command no price, however useful or needful it may be. But he proceeds to add, that things which have the greatest value in exchange, as a diamond for example, may have little or no value in use. This is employing the word "use," not in the sense in which political economy is concerned with it, but in that other sense in which use is opposed to pleasure. Political economy has nothing to do with the comparative estimation of different uses in the judgment of a philosopher or of a moralist. The use of a thing, in political economy, means its capacity to satisfy a desire, or serve a purpose. Diamonds have this capacity in a high degree, and unless they had it, would not bear any price. Value in use, or, as Mr. De Quincey calls it, "teleologic" value, is the extreme limit of value in exchange. The exchange value of a thing may fall short, to any amount, of its value in use; but that it can ever exceed the value in use implies contradiction; it supposes that persons will give, to possess a thing, more than the utmost value which they themselves put upon it, as a means of gratifying their inclinations.

The word "value," when used without adjunct, always means, in political economy, value in exchange.

Here is a queer settlement of phraseology. Let us pick out the positive statements. They are: That Adam Smith was wrong in saying that things which have the greatest value in exchange, as a diamond, may have little or no value in use, because the use of a thing in political economy, which knows nothing of any moral estimate of uses, means its capacity to satisfy a desire or serve a purpose — a capacity which diamonds have in high degree, and unless they had it would not have any value in exchange ("bear any price"). Value in use is the highest possible ("extreme limit of") value in exchange. The exchange value of a thing can never exceed the use value of a thing. To suppose that it could implies a contradiction — that persons will give to possess a thing more than its utmost use value to them ("value which they themselves put upon it as a means of gratifying their inclinations").

In this there is a complete identification of value in use, utility or usefulness, with value in exchange, exchangeability or purchasing power. What then becomes of Mill's other statement in the same paragraph? If Adam Smith was wrong in saying that the exchange value of a thing may be more than its use value, how could he be right in saying that the exchange value of a thing may be less than its use value? If value in use is the highest limit of value in exchange, is it not necessarily the lowest limit? If diamonds derive their exchange value from their capacity to satisfy a desire or serve a purpose, do not beans? If value in exchange means merely value in use, why does Mr. Mill distinguish between the two senses of the word value, that of usefulness, and that of purchasing power? Why does he tell us that the word value, when used without adjunct, always means in political economy value in exchange? Why keep up a distinction where there is really no difference?

In this identification of utility with "desiredness" (which I have merely quoted Mill to illustrate, for it began immediately after Adam Smith, and was well rooted in the current political economy long before Mill, as he indeed declares, saying in the first paragraph of his treatment of values, "Happily there is nothing in the laws of value which remains for the present or any future writer to clear up; the theory of the subject is complete") is the beginning of that theory of value as springing from marginal utilities of which Jevons was the first English expounder, and which has been carried to elaborate development by what is known as the Austrian or psychological school. This school, setting aside all distinction between value in use and value in exchange, makes value without distinction an expression of the intensity of desire, thus tracing it to a purely mental or subjective origin. In this theory the intensity of the desire of the bread-eater to eat bread fixes the extreme or marginal utility of bread. This again fixes the utility of the products of which bread is made — flour, yeast, fuel, etc. — and of the tools used in making it — ovens, pans, etc. — and again of the natural materials used in making these products, and finally of the land and labor.

But all this elaborate piling of confusion on confusion originates, as we may see in Mill, in a careless use of words. Nothing indeed could more strikingly illustrate the need of the warning as to the use of words in political economy which I endeavored to impress on the reader in the introductory chapter of this work than the spectacle here presented of the author of the most elaborate work on logic in the English language falling into vital error in what he himself declares to be a most fundamental question of political economy, from failure to apprehend a distinction in the meaning of two common words. Yet here plainly enough is the source of Mill's acceptance of what much inferior thinkers to Adam Smith had deemed a correction of the great Scotsman. The gist of his argument is that the capability of "a use," in the sense of satisfying a desire or serving a purpose, is identical with usefulness. But this is not so. Every child learns long before he reaches his teens that the capability of a use is not usefulness. Here, for instance, is a dialogue such as every one who has gone to an old-fashioned primary school or mixed as a boy with boys must have heard time and again:

First Boy — What's the use of that crooked pin you're bending?

Second Boy — What's the use! Its use is to lay it on a seat some fellow is just going to sit down on, and to make him jump and squeal, and to hear the teacher charging around while you're busy studying your lesson, and don't know anything about what's the matter.

This is certainly a use; but would any one, even a school-boy, attribute usefulness to such a use?

So, the wearing of nose-rings by some savages; the tattooing of their bodies by other savages, and by sailors; the squeezing of their waists by civilized women; the monstrous structures into which the hair of fashionable European ladies was built in the last century; the hooped skirts worn during a part of this; the pitiful distortion practiced on the feet of upper-class female infants by the Chinese, are all uses. But do they therefore imply usefulness?

Again, the thumb-screws brought from Russia by Drummond and Dalziel, when they were sent to Scotland by Charles II to force Episcopacy upon the Covenanters, had "a use." The racks which the English captors of the ships of the Spanish Armada were said to have found in those vessels, intended, as was believed, for the purpose of converting English Protestants to the true faith of Rome, had also a capacity of satisfying a devilish desire. They had unquestionably at that time value in exchange, and indeed, if still in existence, would have value in exchange now, for they would be purchased for museums; and I do not see how they could at that time have been refused, or if in existence, could now be refused, a place in any category of articles of wealth. But were they useful articles? No one would now say so. There were, it is true, at that time some people who might have contended for their usefulness. But consider the supposition under which alone this claim for their usefulness could have been made, for it points to an essential distinction between the meaning of usefulness and that of mere capacity for use. The thumb-screws and racks could have been considered as useful only on the assumption that the eternal salvation of men, their exemption from endless torture, depended on their acceptance of certain theological beliefs, and therefore that the rooting out of schism and heresy, even by the use of temporal torture, was conducive to the true welfare and final happiness of the generality of mankind.

To consider this is to see that what is really the essential idea of usefulness, of that quality of a thing which Adam Smith distinguished as utility or value in use, is, not the capability of any use, but the capability of use in the satisfaction of the natural, normal and general desires of men.

And in this Adam Smith, following the Physiocrats, recognized a distinction that he did not create, and that no confusions of current economic teaching can eradicate; a distinction that does not come from the refinements of philosophers or moralists, but that rests on common perceptions of the human mind — the distinction, namely, between things which in themselves or in their uses conduce to well-being and happiness and the things which in themselves or in their uses involve fruitless effort or ultimate injury and pain. The capacity of satisfying some desire, no matter how idle, vicious or cruel, is indeed all that is necessary to exchangeability or value in exchange. But to give usefulness or value in use something more is necessary, and that is the capacity to satisfy, not any possible desire, but those desires which we call needs or wants, and which, lying lower in the order of desires, are felt by all men.**

Value in use and value in exchange may and often do attach to the same things, and, as a matter of fact, doubtless the great majority of things having value in exchange have also value in use. But this connection is not necessary, and the two qualities have no relation whatever to each other. A thing may have use value in the highest degree, yet very little exchange value or none at all. A thing may have exchange value in very high degree and little or no use value. Air has the highest value in use, as without air we could not live a minute. But this supreme utility does not give air exchange value. The Bambino of Rome or the Holy Coat of Treves could probably be exchanged, as similar venerated objects have been at times exchanged, for enormous sums; but the use value of the one is that of a wax doll baby, that of the other an old rag. The two qualities of value in use and value in exchange are as essentially different and unrelatable as are weight and color, though as we sometimes speak of heavy browns and light blues, so do we in common speech use the word value now to express one of these qualities and now the other. The quality of value in use is an intrinsic or inherent quality attaching to the thing itself, and giving to it fitness to satisfy man's needs. It cannot have value in use except it has that, and as it has that, no matter what be its value in exchange. And its use value is the same whether much can be obtained for it in exchange or "no one would pick it up." The quality of value in exchange, on the other hand, is not intrinsic or inherent.

There is, to be sure, a special sense in which, comformably to usage, we may speak in certain cases of an intrinsic value as applying to the part of the value which comes wholly from the estimate of man, and where in reality inherent or intrinsic value cannot exist. The cases in which we do this are cases in which we wish to distinguish between the exchange value which a thing may have in a higher or more valuable form and that exchange value which still remains if it were reduced to a lower or less valuable form. Thus, a silver pitcher or a United States silver coin would lose exchange value if beaten into ingots; or a coil of lead pipe or a ship's anchor and cable would lose in exchange value if melted into pigs. Yet they would retain the exchange value of the metal from which they were made. This value in exchange which would remain in a lower form we are accustomed to speak of as "intrinsic value." But in using this term we should always remember its merely relative sense. Value in the economic sense, or value in exchange, can never really be intrinsic. It refers not to any property of the thing itself, but to an estimate that is placed on it by man — to the toil and trouble that men will undergo to acquire possession of it, or the amount of other things costing toil and trouble that they will give for it.

Nor is there any common measure in the human mind between usefulness and exchangeability. Whether we most esteem a thing for the intrinsic qualities that give it usefulness, or for its intrinsic quality of commanding other things in exchange, depends upon conditions.

A daring fellow recently crossed from the coast of Norway to the United States in a sixteen-foot boat. Supposing him to come to New York, and one of our hundredfold millionaires, in the fashion of an Arabian Nights' Sultan, to say to him: "If you will make a trip at my direction you may fill up your boat at my expense with anything you choose to take from New York, regardless of its cost." What would he fill it up with? That could not be answered in a word, as it would entirely depend upon where the millionaire wanted him to go. If he were merely to cross the North River from New York to Jersey City, he would disregard value in use and fill up with what had the highest value in exchange, in comparison to bulk and weight — gold, diamonds, paper money. To carry the more of these he would leave out everything having value in use that he could get along without for an hour or two — even to extra sails, anchor, sea — drag, compass, a morsel of food or a drink of water. But if he were to cross the Atlantic again, his first care would be for things useful in the management of his boat and the maintenance of his own life and comfort during the long months of danger and solitude before he could hope again to reach land. He would regard value in use, disregarding value in exchange. If he had not lost the prudence which, no less than daring, is required successfully to make such a trip, it may well be doubted whether he would not prefer to carry its weight in fresh water than to take a single diamond or gold piece and prefer another can of biscuit or condensed beef to the last bundle of thousand-dollar notes that he might take instead.

Adam Smith was right. The distinction between value in use and value in exchange is an essential one. It is so clear and true and necessary that, as we have seen, John Stuart Mill could not refrain from partially recognizing it in the very breath in which he had eliminated it altogether, and the later economists who have carried the confusion which he expresses to a point of more elaborate confusion are also compelled to recognize it the moment they get out of the fog of ill-understood words. Despite all attempts to confuse and obliterate them, "value in use" and "value in exchange" must still hold their place in economic terminology. The terms themselves are perhaps not the happiest that might be chosen. But so long have they now been used that it would be difficult to substitute anything in their place. It is only necessary to do what Adam Smith could hardly have deemed necessary — point out what they really mean. They were taken indeed by him from common speech, and still retain the great advantage to any economic term of being generally intelligible.

In common speech the one word value, as I have already said, usually suffices to express either value in use or value in exchange. For which sense of the word value is meant is ordinarily indicated with sufficient clearness either by the context or by the situation or nature of the thing spoken of. But in cases where there is no indication thus supplied, or the indication is not sufficiently clear, the use of the word "value" will at once provoke a question equivalent to "Do you mean value for use or value for exchange?"

Thus, if a man says to me, "That is a valuable dog, he saved a child from drowning;" I know that the value he means is value in use. If he says, however, "That is a valuable dog, his brother brought a hundred dollars;" I know that he has in mind value in exchange. Even where he says simply, "That is a valuable dog," there is generally some indication that enables me to tell what sense of value he has in mind. If there is none, and I am interested enough to care, I ask for it by such question as "Why?" or "What for?"

In economic reasoning, however, the danger of using one word to represent two distinct and often contrasted ideas is very much greater than in common speech, and it the word is to be retained, one of its senses must be abandoned. Of the two meanings of the word value, the first, that of value in use, is not called for, or called for only incidentally in political economy; while the second, that of value in exchange, is called for continually, for this is the value with which political economy deals. To economize the use of words, while at the same time avoiding liability to misunderstanding and confusion, it is expedient, therefore, to restrict the use of the word value, as an economic term, to the meaning of value in exchange, as was done by Adam Smith, and has since his time generally been followed; and to discard the use of the single word value in the sense of value in use, substituting for it where there is occasion to express the idea of value in use, and the close context does not clearly show the limitation of meaning, either the term "value in use" or some such word as usefulness or utility. This I shall endeavor to do in this work — using hereafter the single term value, as meaning purchasing power or "value in exchange."

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263