Confusions about Meaning of Wealth

Epigraphs to Book IIDefinitions are the basis of systematic reasoning. — Aristotle The mixture of those things by speech which are by nature divided is the mother of all error. — Hooker Bacon made us sensible of the emptiness of the Aristotelian philosophy; Smith, in like manner, caused us to perceive the fallaciousness of all the previous systems of political economy; but the latter no more raised the superstructure of this science, than the former created logic.... We are, however, not yet in possession of an established text-book on the science of political economy, in which the fruits of an enlarged and accurate observation are referred to general principles that can be admitted by every reflecting mind; a work in which these results are so complete and well arranged as to afford to each other mutual support, and that many everywhere and at all times be studied with advantage. — J.B. Say, 1803 We may cite as examples of such inchoate but yet incomplete discoveries the great Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith — a work which still stands out, and will ever stand out, as that of a pioneer, and the only book on political economy which displays its genius to every kind of intelligent reader. But among the specialists and the schools, this work of genius which swayed all Europe in its day, is laid upon the shelf as an antiquated affair, superseded by the smaller and duller men who have pulled his system to pieces and are offering us the fragments as a science most of whose first principles are still under dispute. — Professor (Greek) J.P. Mahaffy, "The Present Position of Egyptology," "Nineteenth Century," August, 1894. Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works. |

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

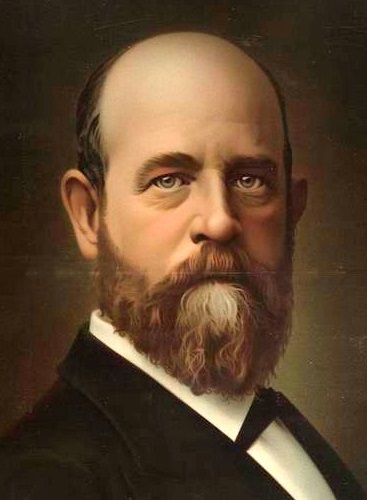

Henry George

|

Wealth the primary term of political economy — Common use of the word — Vagueness more obvious in political economy — Adam Smith not explicit — Increasing confusion of subsequent writers — Their definitions — Many make no attempt at definition — Perry's proposition to abandon the term — Marshall and Nicholson — Failure to define the term leads to the abandonment of political economy — This concealed under the word "economic" — The intent expressed by Macleod — Results to political economy

The purpose of the science of political economy is, as we have seen, the investigation of the laws that govern the production and distribution of wealth in social or civilized life. In beginning its study, our first step is therefore to see what is the nature of the wealth of societies or communities; to determine exactly what we mean by the word wealth when used as a term of political economy.

There are few words in more common use than this word wealth, and in the general way that suffices for ordinary purposes we all know what we mean by it. But when it comes to defining that meaning with the precision necessary for the purposes of political economy, so as to determine what is and what is not properly included in the idea of wealth as political economy must treat of it, most of us, though we often and easily use the word in ordinary thought and speech, are apt to become conscious of indefiniteness and perplexity.

This is not strange. Indeed, it is a natural result of the transference to a wider economy of a term we are accustomed to use in a narrower economy. In our ordinary thought and speech, referring, as it most frequently does, to everyday affairs and the relations of individuals with other individuals, the economy with which we are usually concerned and have most frequently in mind is individual economy, not political economy — the economy whose standpoint is that of the unit, not the economy whose standpoint is that of the social whole or social organism; the Greater Leviathan of natural origin of which I have before spoken.

The original meaning of the word wealth is that of plenty or abundance; that of the possession of things conducive to a certain kind of weal or well-being. Health, strength and wealth express three kinds of weal or wellbeing. Health relates to the constitution or structure, and expresses the idea of well-being with regard to the physical or mental frame. Strength relates to the vigor of the natural powers, and expresses the idea of well-being with regard to the ability of exertion. Wealth relates to the command of external things that gratify desire, and expresses the idea of well-being with regard to possessions or property. Now, as social health must mean something different from individual health, and social strength something different from individual strength; so social wealth, or the wealth of the society, the larger man or Greater Leviathan of which individuals living in civilization are components, must be something different from the wealth of the individual.

In the one economy, that of individuals or social units, everything is regarded as wealth the possession of which tends to give wealthiness, or the command of external things that satisfy desire, to its individual possessor, even though it may involve the taking of such things from other individuals. But in the other economy, that of social wholes, or the social organism, nothing can be regarded as wealth that does not add to the wealthiness of the whole. What, therefore, may be regarded as wealth from the individual standpoint, may not be wealth from the standpoint of the society. An individual, for instance, may be wealthy by virtue of obligations due to him from other individuals; but such obligations can constitute no part of the wealth of the society, which includes both debtor and creditor. Or, an individual may increase his wealth by robbery or by gaming, but the wealth of the social whole, which comprises robbed as well as robber, loser as well as winner, cannot be thus increased.

It is therefore no wonder that men accustomed to the use of the word wealth in its ordinary sense, a sense in which no one can avoid its continual use, should be liable, unless they take great care, to slip into confusion when they come to use the same word in its economic sense. But what does seem strange is that indefiniteness, perplexity and confusion as to the meaning of the economic term wealth, are even more obvious in the writings of the professional economists who are accredited by colleges and universities and other institutions of learning with the possession of special knowledge which authorizes them to instruct their fellows on economic subjects. While as for the professional statisticians who in long arrays of figures attempt to estimate the aggregate wealth of states and nations, they seem for the most part innocent of any suspicion that what may be wealth to an individual may not be wealth to a community.*

Adam Smith, who is regarded as the founder of the modern science of political economy, is not very definite or entirely consistent as to the real nature of the wealth of nations, or wealth in the economic sense. But since his time the confusions of which he shows traces, instead of being cleared up by the writings of those who in our schools and colleges are recognized as political economists, ** has become progressively so much worse confounded that in the latest and most elaborate of these treatises all attempts to define the term seem to have been abandoned.

In Progress and Poverty (1879), I showed the utter confusion as to wealth into which the scholastic political economy had fallen, by printing together a number of varying and contradictory definitions of its sub-term capital, as given by accredited economic writers.*** Although I was then obliged to fix the meaning of the main term wealth in order to fix the meaning of the sub-term capital, with which I was immediately concerned, the confusion among the accredited economists has "got no better very fast," the "economic revolution" which has in the meanwhile displaced from their chairs the professors of the then orthodox political economy in order to give place to so-called "Austrians," or similar professors of "economics," having only made confusion worse confounded. Let me, therefore, in order to show in the most up-to-date way the confusion existing among scholastic economists as to the primary term of political economy, put together what definitions of the economic term wealth I can find in the works of representative and accredited economic writers since Adam Smith to the present time, placing them in chronological order as far as possible:

J. B. Say — Divides wealth into natural and social, and applies the latter term to whatever is susceptible of exchange.

Malthus — Those material objects which are necessary, useful or agreeable to man.

Torrens — Articles which possess utility and are produced by some portion of voluntary effort.

McCulloch — Those articles or products which have exchangeable value, and are either necessary, useful or agreeable to man.

Jones — Material objects voluntarily appropriated by man.

Rae — All I can find on this subject in his New Principles of Political Economy (1833) is that "individuals grow rich by the acquisition of wealth previously existing; nations by the creation of wealth that did not before exist."

Senior — All those things, and those things only, which are transferable, are limited in supply, and are directly or indirectly productive of pleasure or preventive of pain. . . . Health, strength and knowledge, and the other acquired powers of body and mind, appear to us to be articles of wealth.

Vethake — All objects, immaterial as well as material, having utility, excepting those not susceptible of being appropriated, and those supplied gratuitously by nature. By the wealth of a community or nation is meant all the wealth which is possessed by the persons composing it, either in their individual or corporate capacities.

John Stuart Mill — All useful and agreeable things which possess exchangeable value; or in other words, all useful and agreeable things except those which can be obtained, in the quantity desired, without labor or sacrifice.

Fawcett — Wealth may be defined to consist of every commodity which has an exchangeable value.

Bowen — The aggregate of all things, whether material or immaterial, which contribute to comfort and enjoyment and which are objects of frequent barter and sale.

Jevons — What is (1) transferable, (2) limited in supply, (3) useful.

Mason and Lalor, 1875 — Anything for which something can be got in exchange.

Leverson — The necessaries and comforts of life produced by labor.

Shadwell — All articles the possession of which affords pleasure to anybody.

Macleod — Anything whatever that can be bought, sold or exchanged, or whose value can be measured in money.... Wealth is nothing but exchangeable rights.

De Laveleye — Everything which answers to men's rational wants. A useful service and a useful object are equally wealth.... Wealth is what is good and useful — a good climate, well-kept roads, seas teeming with fish, are unquestionably wealth to a country, and yet they cannot be bought.

Francis A. Walker — All articles of value and nothing else.

Macvane — All the useful and agreeable material objects we own or have the right to use and enjoy without asking the consent of any other person. Wealth is of two general kinds — natural wealth and wealth produced by labor.

Clark — Usage has employed the word wealth to signify, first, the comparative welfare resulting from material possessions, and secondly, and by a transfer, the possessions themselves. Wealth then consists in the relative-weal-constituting elements in man's material environment. It is objective to the user, material, useful and appropriable.

Laughlin — Defines material wealth as something which satisfies a want; cannot be obtained without some sacrifice of exertion, and is transferable; but also speaks of immaterial wealth without defining it.

Newcomb — That for the enjoyment of which people pay money. The skill, business ability or knowledge which enables their possessors to contribute to the enjoyment of others, including the talents of the actor, the ability of the man of business, the knowledge of the lawyer and the skill of the physician, is to be considered wealth when we use the term in its most extended sense.

Bain — A commodity is material worked up after a design to answer to a definite demand or need, and wealth is simply the sum total of commodities.

Ruskin — This brilliant essayist and art critic can hardly be classed as a scholastically accepted political economist, and I have refrained from giving his definition of wealth in what otherwise would have been its proper place. But his Unto this Last (1866) consists of four essays on political economy, and the brilliant flashes of ethical truth which they like his other works contain have led many admirer to regard him as a profound economist. He is anything but complimentary to the "modern soi-disant science," as he calls it, against which he brings the charge that while claiming to be the science of wealth it cannot tell what wealth is. In the preface to these essays he says: "The real gist of these papers, their central meaning and aim is to give, as I believe, for the first time in plain English, a logical definition of wealth; such definition being absolutely needed for a basis of economical science." It would be well, therefore, without assuming that Ruskin in any way represents the scholastic political economy, which he likened to an astronomy unable to say what a star was, to give his definition. That definition, to use his own words is — "The possession of useful articles that we can use," or as again stated somewhat later on, "The possession of the valuable by the valiant."

The endeavor to get together these definitions of wealth by economic writers has involved considerable effort, but it is likely to be noticeable by its omissions. The fact is, that many of the best-known writers on political economy, such for instance as Ricardo, Chalmers, Thorold Rogers and Cairnes, make no attempt to give any definition of wealth. The same thing is to be said of the two volumes of Karl Marx entitled Capital; and also of the two volumes on the same subject by Bohm-Bawerk, which also have been translated into English, and are much quoted by that now dominant school of scholastic political economy known as the "Austrian." And while many of the writers who make no attempt to define wealth, do have a good deal to say about it, what they say is too diffused and incoherent either to quote or condense. There are many who without saying so, evidently hold the opinion thus frankly expressed by Professor Perry in his Elements of Political Economy (1866):

This word wealth has been the bane of political economy. It is the bog whence most of the mists have arisen which have beclouded the whole subject. From its indefiniteness and the variety of associations it carries along with it in different minds, it is totally unfit for any scientific purpose whatever. It is itself almost impossible to be defined, and consequently can serve no useful purpose in a definition of anything else.... The meaning of the word wealth has never yet been settled; and if political economy must wait until that work be done as a preliminary, the science will never be satisfactorily constructed.... Men may think, and talk, and write, and dispute till doomsday, but until they come to use words with definiteness, and mean the same thing by the same word, they reach comparatively few results and make but little progress. And it is just at this point that we find the first grand reason of the slow advance hitherto made by this science. It undertook to use a word for scientific purposes which no amount of manipulation and explanation could make suitable for that service. Happily there is no need to use this word. In emancipating itself from the word wealth as a technical term, political economy has dropped a clog, and its movements are now relatively free.

To make this exhibition of definitions as fairly representative as possible I have wished to include in it that of Professor Alfred Marshall, Professor of Political Economy in the University of Cambridge, England, whose Principles of Economics (of which only the first volume, issued in 1890, and containing some 800 octavo pages, has yet been published) may be considered the latest and largest, and scholastically the most highly indorsed, economic work yet published in English.

It cannot be said of him, as of many economic writers, that he does not attempt to say what is meant by wealth, for if one turns to the index he is directed to a whole chapter. But neither in this chapter nor elsewhere can I find any paragraph, however long, that may be quoted as defining the meaning he attaches to the term wealth. The only approach to it is this:

All wealth consists of things that satisfy wants, directly or indirectly. All wealth therefore consists of goods; but not all kind of goods are reckoned as wealth.

But for the distinction between goods reckoned as wealth and goods not reckoned as wealth, which one would think was about to follow, the reader looks in vain. He merely finds that Professor Marshall gives him the choice of classifying goods into external-material- transferable goods, external-material-non-transferable goods, external-personal-transferable goods, external-personal-non-transferable goods, and internal-personal-non-transferable goods; or else into material-external-transferable goods, material-external-non- transferable goods, personal-external-transferable goods, personal-external-non-transferable goods, and personal-internal-non-transferable goods. But as to which of these kinds of goods are reckoned as wealth and which are not, Professor Marshall gives the reader no inkling, unless, indeed, he may be able to find it in Wagner's Volkswirthschaftslehre, to which the reader is referred at the conclusion of the chapter as throwing "much light upon the connection between the economic concept of wealth and the juridical concept of rights in private property." I can convey the impression produced on my mind by repeated struggles to discover what the Professor of Political Economy in the great English University of Cambridge holds is to be reckoned as wealth, only by saying that it seems to comprise all things in the heavens above, the earth beneath and the waters under the earth, that may be useful to or desired by man, individually or collectively, including man himself with all his natural or acquired capabilities, and that all I can absolutely affirm, for it is the only thing for which I can find a direct statement, is, that "we ought for many purposes to reckon the Thames a part of England's wealth."

The same utter, though perhaps somewhat less elaborate, incoherency is shown by Professor J. Shield Nicholson, Professor of Political Economy in the great Scottish University of Edinburgh, whose Principles of Political Economy appeared in first volume (less than half as big as that of Professor Marshall's) in 1893, and has not yet (1897) been succeeded by another. Looking up the index for the word "wealth" one finds no less than fifteen references, of which the first is "popular conception of," and the second "economic conception of." Yet in none of these, nor in the whole volume, though one wade through it all in the search, is anything like a definition of wealth to be found, the only thing resembling a direct statement being the incidental remark (p. 404) that "land is in general the most important item in the inventory of national wealth" — a proposition which logically is as untrue as that we ought to reckon the Thames a part of England's wealth.

Now, wealth is the object-noun, or name given to the subject-matter, of political economy, the science that seeks to discover the laws of the production and distribution of wealth in human society. It is therefore the economic term of first importance. Unless we know what wealth is, how possibly can we hope to discover how it is procured and distributed? Yet after a century of what passes for the cultivation of this science, with professors of political economy in every college, the question, "What is wealth?" finds at their hands no certain answer. Even to such questions as, "Is wealth material or immaterial?" or "Is it something external to man or does it include man and his attributes?" we get no undisputed reply. There is not even a consensus of opinion. And in the latest and most pretentious scholastic teaching the attempt to obtain any has been virtually, where not definitely, abandoned, and the economic meaning of wealth reduced to that of anything having value to the social unit.

It is clear that failure to define its subject-matter or object-noun must be fatal to any attempted science; for it shows lack of the first essential of true science. And the fate of rejection even by those who profess to study and teach it has already befallen political economy at the hands of the accredited institutions of learning.

This fact will not be obvious to the ordinary reader, for it is concealed to him under a change in the meaning of a word.

Since the term comes into our language from the Greek, the proper word for expressing the idea of relationship to political economy is "politico-economic." But this is a term too long, and too alien to the Saxon genius of our mother tongue, for frequent repetition. And so the word "economic" has come into accepted use in English, as expressing that idea. We are justified therefore, in supposing, and as a matter of fact do generally suppose when we first hear of them, that the works now written by the professors of political economy in our universities and colleges, and entitled Elements of Economics, Principles of Economics, Manual of Economics, etc., are treatises on political economy. Examination, however, will show that many of these at least are not in reality treatises on the science of political economy, but treatises on what their authors might better call the science of exchanges, or the science of exchangeable quantities. This is not the same thing as political economy, but quite a different thing — a science in short akin to the science of mathematics.**** In this there is no necessity for distinguishing between what is wealth to the unit and what is wealth to the whole, and moral questions, that must be met in a true political economy, may be easily avoided by those to whom they seem awkward.

A proper name for this totally different science, which the professors of political economy in so many of the leading colleges and universities on both sides of the Atlantic have now substituted in their teaching for the science they are officially supposed to expound, would be that of "catallactics," as proposed by Archbishop Whately, or that of "plutology," as proposed by Professor Hern, of Melbourne; but it is certainly not properly "economics," for that by long usage is identified with political economy.

Both the reason for, and what is meant by, the change of title from political economy to economics, which is so noticeable in the writings of the professors of political economy in recent years, are thus frankly shown by Macleod (Vol. I, Chapter VII, Sec. 11, Science of Economics):

We do not propose to make any change at all in the name of the science. Both the terms "Political Economy" and "Economic Science," or "Economics," are in common use, and it seems better to discontinue that name which is liable to misinterpretation, and which seems to relate to politics, and to adhere to that one which most clearly defines its nature and extent and is most analogous to the names of other sciences. We shall, therefore, henceforth discontinue the use of the term "political economy" and adhere to that of "economics." Economics, then, is simply the science of exchanges, or of commerce in its widest extent and in all its forms and varieties; it is sometimes called the science of wealth or the theory of value. The definition of the science which we offer is:

Economics is the science which treats of the laws which govern the relations of exchangeable quantities.

Now the laws which govern the relations of exchangeable quantities are such laws as 2 + 2 = 4; 4 – 1 = 3; 2 x 4 = 8; 4/2 = 2; and their extensions.

The proper place for such laws in any honest classification of the sciences is as laws of arithmetic or laws of mathematics, not as laws of economics. And the attempt of holders of chairs of political economy to take advantage of the usage of language which has made "economic" a short word for "politico-economic" to pass off their "science of economics" as if it were the science of political economy, is as essentially dishonest as the device of the proverbial Irishman who attempted to cheat his partners by the formula, "Here's two for you two, and here's two for me too."

To this, in less than a century after Say congratulated his readers on the first establishment of chairs of political economy in universities, has the scholastic political economy come.

Professor Perry, writing thirty years ago, thought that by emancipating itself from the word wealth as a technical term, political economy would drop a clog and its movements would become relatively free. In what is now taught from the chairs of political economy in our leading colleges on both sides of the Atlantic the clog has indeed been dropped, with results which very strongly suggest the increased freedom of movement which comes from the dropping of its tail by a boy's kite. Without the clog of an object — noun, political economy as there taught has plunged out of existence, and the science of values which is taught in its place has no answer whatever to give even to questions which Professor Perry would have thought completely settled at the time he wrote.

* A curious, if not comical, instance of the loose way in which professed statisticians jump at conclusions is afforded in the controversy I had in "Frank Leslie's Weekly" (1883) with Professor Francis A. Walker, then superintendent of the United States Census, and which was afterwards reprinted as an appendix to the American edition of my "Social Problems."

** Progress and Poverty, although it has already exerted a wider influence than any other economic work written since the Wealth of Nations, is not so recognized, not being even alluded to in the elaborate history of political economy which, on account of the utter chaos into which the teachings of that science have fallen, takes in the last edition of the "Encyclopedia Britannica" the place before accorded to the science itself, and which has since been reprinted in separate form. ("A History of Political Economy," by John Kells Ingram, LL.D., Macmillan & Co., 1888.)

*** Progress and Poverty, Book I, Chapter II, "The Meaning of the Terms."

**** The attempts by titular professors of political economy to find mathematical expression for what they call "economics" must be familiar to those who have toiled through recent scholastic literature.

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263