Meaning of Political Economy

Epigraph to Book IThough but an atom midst immensity, -- Bowring's translation of Dershavin Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works.

|

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

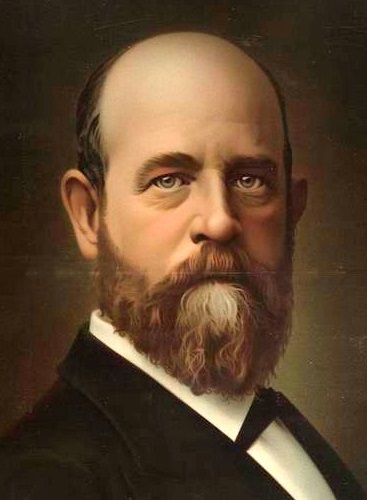

Henry George

|

The word economy, drawn from two Greek words, house and law, which together signify the management or arrangement of the material part of household or domestic affairs, means in its most common sense the avoidance of waste. We economize money or time or strength or material when we so arrange as to accomplish a result with the smallest expenditure. In a wider sense its meaning is that of a system or arrangement or adaptation of means to ends or of parts to a whole. Thus, we speak of the economy of the heavens; of the economy of the solar systems; the economy of the vegetable or animal kingdoms: the economy of the human body; or, in short, of the economy of anything which involves or suggests the adaptation of means to ends, the coordination of parts in a whole.

As there is an economy of individual affairs, an economy of the household, an economy of the farm or workshop or railway, each concerned with the adaptation in these spheres of means to ends, by which waste is avoided and the largest results obtained with the least expenditure, so there is an economy of communities, of the societies in which civilized men live -- an economy which has special relation to the adaptation or system by which material wants are satisfied, or to the production and distribution of wealth.

The word political means, relating to the body of citizens or state, the body politic; to things coming within the scope and action of the commonwealth or government; to public policy.

Political economy, therefore, is a particular kind of economy. In the literal meaning of the words it is that kind of economy which has relation to the community or state; to the social whole rather than to individuals.

But the convenience which impels us to abbreviate a long term has led to the frequent use of "economic" when "politico-economic" is meant, so that we may by usage speak of the literature of principles or terms of political economy as "economic literature," or "economic principles," or "economic terms." Some recent writers, indeed, seem to have substituted the term "economics" for political economy itself. But this is a matter as to which the reader should be on his guard, for it has been used to make what is not really political economy pass for political economy, as I shall hereafter show.

Adam Smith, who at the close of the last century gave so powerful an impulse to the study of what has since been called political economy that he is, not without justice, spoken of as its father, entitled his great book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Cause of the Wealth of Nations; and what we call political economy the Germans call national economy.

No term is of importance if we rightly understand what it means. But, both in the term "political economy," and in that of "national economy," as well as in the phrase "wealth of nations," lurk suggestions which may and in fact often do interfere with a clear apprehension of the ground they properly cover.

The use of the term "political economy" began at a time when the distinction between natural law and human law was not clearly made, when what I have called the body economic was largely confounded with what is properly the body politic, and when it was the common opinion in Europe, even of thoughtful men, that the production and distribution of wealth were to be regulated by the legislative action of the sovereign or state.

The first one to use the term is said to have been Antoine de Montchretien in his Treatise on Political Economy (Traité de l’économie politique), published in Rouen, France, 1615. But if not invented by them, it was given currency, some 130 or 140 years after, by those French exponents of natural right, or the natural order, who may today be best described as the first single-tax men. They used the term "political economy" to distinguish from politics the branch of knowledge with which they were concerned, and from this called themselves Economists. The term is used by Adam Smith only in speaking of "this sect," composed of "a few men of great learning and ingenuity in France." But although these Economists were overwhelmed and have been almost forgotten, yet of their "noble and generous system" this term remained, and since the time of Adam Smith it has come into general use as expressive of -- to accept the most common and I think sufficient definition -- that branch of knowledge that treats of the nature of wealth, and the laws of its production and distribution.

But the confusion with politics, which the Frenchmen of whom Adam Smith speaks endeavored to clear away by their adoption of the term "political economy," still continues and is in fact suggested by the term itself, which seems at first apt to convey the impression of a particular kind of politics rather than of a particular kind of economy. The word political has a meaning which relates it to civil government, to the exercise of human sovereignty by enactment or administration, without reference to those invariable sequences which we call natural laws. An area differentiated from other areas with reference to this power of making municipal enactments and compelling obedience to them, we style a political division; and the larger political divisions, in which the highest sovereignty is acknowledged, we call nations. It is therefore important to keep in mind that the laws with which political economy primarily deals are not human enactments or municipal laws, but natural laws; and that they have no more reference to political divisions than have the laws of mechanics, the laws of optics or the laws of gravitation.

It is not with the body politic, but with that body social or body industrial that I have called the body economic, that political economy is directly concerned; not with the commonwealth of which a man becomes a member by the attribution or acceptance of allegiance to prince, potentate or republic; but with the commonwealth of which he becomes a member by the fact that he lives in a state of society in which each does not attempt to satisfy all of his own material wants by his own direct efforts, but obtains the satisfaction of some of them at least through the cooperation of others. The fact of participation in this cooperation does not make him a citizen of any particular state. It makes him a civilized man, a member of the civilized world -- a unit in that body economic to which our political distinctions of states and nations have no more relation than distinctions of color have to distinctions of form.

The unit of human life is the individual. From our first consciousness, or at least from our first memory, our deepest feeling is, that what we recognize as "I" is something distinct from all other things, and the actual mergement of its individuality in other individualities, however near and dear, is something we cannot conceive of. But the lowest unit of which political economy treats often includes the family with the individual. For though isolated individuals may exist for a while, it is only under unnatural conditions. Human life, as we know it, begins with the conjuncture of individuals, and even for some time after birth can continue to exist only under conditions which make the new individual dependent on and subject to preceding individuality; while it requires for its fullest development and highest satisfactions the union of individuals in one economic unit.

While, then, in treating of the subject-matter of political economy, it will be convenient to speak of the units we shall have occasion to refer to as individuals, it should be understood that this term does not necessarily mean separate persons, but includes, as one, those so bound together by the needs of family life as to have, as our phrase is, "one purse."

An economy of the economic unit would not be a political economy, and the laws of which it would treat would not be those with which political economy is concerned. They would be the laws of personal or family conduct. An economy of the individual or family could treat the production of wealth no further than related to the production of such a unit. And though it might take cognizance of the physical laws involved in its agriculture and mechanics, of the distribution of wealth in the economic sense it could not treat at all, since any apportionment among the members of such a family of wealth obtained by it would be governed by the laws of individual or family life, and not by any law of the distribution of the results of socially conjoined effort.

But when in the natural course of human growth and development economic units come into such relations that the satisfaction of material desires is sought by conjoined effort, the laws which political economy seeks to discover begin to appear.

The system or arrangement by which in such conditions material satisfactions are sought and obtained may be roughly likened to a machine fed by combined effort, and producing joint results, which are finally divided or distributed in individual satisfactions -- a machine resembling an old-time grist-mill to which individuals brought separate parcels of grain, receiving therefrom in meal, not the identical grain each had put in, nor yet its exact equivalent, but an equivalent less a charge for milling.

Or to make a closer illustration: The system or arrangement which it is the proper purpose of political economy to discover may be likened to that system or arrangement by which the physical body is nourished. The lowest unit of animal life, so far as we can see, is the single cell, which sucks in and assimilates its own food; thus directly satisfying what we may style its own desires. But in those highest forms of animal life of which man is a type, myriads of cells have become conjoined in related parts and organs, exercising different and complex functions, which result in the procurement, digestion and assimilation of the food that nourishing each separate cell maintains the entire organism. Brain and stomach, hands and feet, eyes and ears, teeth and hair, bones, nerves, arteries and veins, still less the cells of which all these parts are composed, do not feed themselves. Under the government of the brain, what the hands, aided by the legs, assisted by the organs of sense, procure, is carried to the mouth, masticated by the teeth, taken by the throat to the alembic of the stomach, where aided by the intestines it is digested, and passing into a fluid containing all nutritive substances, is oxygenized by the lungs; and impelled by the pumping of the heart, makes a complete circuit of the body through a system of arteries and veins, in the course of which every part and every cell takes the nutriment it requires.

Now, what the blood is to the physical body, wealth, as we shall hereafter see more fully, is to the body economic. And as we should find, were we to undertake it, that a description of the manner in which blood is produced and distributed in the physical body would involve almost, if not quite, a description of the entire physical man with all his powers and functions and the laws which govern their operations; so we shall find that what is included or involved in political economy, the science which treats of the production and distribution of wealth, is almost, if not quite, the whole body social, with all its parts, powers and functions, and the laws under which they operate.

The scope of political economy would be roughly explained were we to style it the science which teaches how civilized men get a living. Why this idea is sufficiently expressed as the production and distribution of wealth will be more fully seen hereafter; but there is a distinction as to what is called getting a living that it may be worthwhile here to note.

We have but to look at existing facts to see that there are two ways in which men (i.e., some men) may obtain satisfaction of their material desires for things not freely supplied to them by nature.

The first of these ways is, by working, or rendering service.

The second is, by stealing, or extorting service.

But there is only one way in which man (i.e., men in general or all men) can satisfy his material desires -- that is by working, or rendering service.

For it is manifestly impossible that men in general or all men, or indeed any but a small minority of men, can satisfy their material desires by stealing, since in the nature of things working or the rendering of service is the only way in which the material satisfactions of desire can be primarily obtained or produced. Stealing produces nothing; it only alters the distribution of what has already been produced.

Therefore, however it be that stealing is to be considered by an individual economy or by an economy of a political division, and with whatever propriety a successful thief who has endowed churches and colleges and libraries and soup -- houses may in such an economy be treated as a public benefactor and spoken of as Antony spoke of Caesar --

-- a true science of political economy takes no cognizance of stealing, except in so far as the various forms of it may pervert the natural distribution, and thus check the natural production of wealth.

Yet, at the same time, political economy does not concern itself with the character of the desires for which satisfaction is sought. It has nothing to do, either with the originating motive that prompts to action in the satisfaction of material desires, nor yet with the final satisfaction which is the end and aim of that action. It is, so to speak, like the science of navigation, which is concerned with the means whereby a ship may be carried from point to point on the ocean, but asks not whether that ship may be a pirate or a missionary barque, what are the expectations which may induce its passengers to go from one place to another, or whether or not these expectations will be gratified on their arrival. Political economy is not moral or ethical science, nor yet is it political science. It is the science of the maintenance and nutriment of the body politic.

Although it will be found incidentally to throw a most powerful light upon, and to give a most powerful support to, the teachings of moral or ethical science, its proper business is neither to explain the difference between right and wrong nor to persuade to one in preference to the other. And while it is in the same way what may be termed the bread-and-butter side of politics, it is directly concerned only with the natural laws which govern the production and distribution of wealth in the social organism, and not with the enactments of the body politic or state.

Comments:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263