Elements of Political Economy

Epigraph to Book IThough but an atom midst immensity, -- Bowring's translation of Dershavin Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works.

|

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

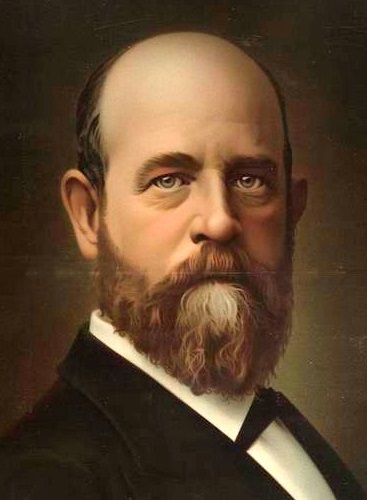

Henry George

|

How to understand a complex system -- It is the purpose of such a system that political economy seeks to discover -- These laws, natural laws of human nature -- The two elements recognized by political economy -- These distinguished only by reason -- Human will affects the material world only through laws of nature -- It is the active factor in all with which political economy deals.

To understand a complex machine the best way is first to see what is the beginning and what the end of its movements, leaving details until we have mastered its general idea and comprehended its purpose. In this way we most easily see the relation of parts to each other and to the object of the whole, and readily come to understand to the minutest movements and appliances what without the clue of intention might have hopelessly perplexed us.

When the safety bicycle was yet a curiosity even in the towns of England and the United States, an American missionary in a far-off station received from an old friend, unaccompanied by the letter intended to go with it, a present of one of these machines, which for economy in transportation had not been set up, but was forwarded in its unassembled parts. How these parts were to be put together was a perplexing problem, for neither the missionary himself nor any one he could consult could at first imagine what the thing was intended to do, and their guesses were of almost everything but the truth, until at length the saddle suggested a theory, which was so successfully followed that by the time, months afterwards, another ship brought the missing letter, the missionary was riding over the hard sand of the beach on his wheel.

In the same way an intelligent savage, placed in a great industrial hive of our civilization before some enormous factory throbbing and whirring with the seemingly independent motion of pistons and wheels and belts and looms, might, with no guide but his own observation and reason, soon come to see the what, the how and the why of the whole as a connected device for using the power obtained by the transformation of coal into heat in the changing of such things as wool, silk or cotton into blankets or piece goods, stockings or ribbons.

Now the reason which enables us to understand the works of man as soon as we discover the reason that has brought them into existence, also enables us to interpret nature by assuming a like reason in nature. The child's question, "What is it for?" -- what is its purpose or intent? -- is the master key that enables us to turn the locks that hide nature's mysteries. It is in this way that all discoveries in the field of the natural sciences have been made, and this will be our best way in the investigation we are now entering upon. The complex phenomena of the production and distribution of wealth in the elaborate organization of modern civilization will only puzzle us, as the many confused and confusing books written to explain it show, if we begin, as it were, from the middle. But if we seek first principles and trace out main lines, so as to comprehend the skeleton of their relation, they will readily become intelligible.

The immense aggregate of movements by which, in civilization, wealth is produced and distributed, viewed collectively as the subject of political economy, constitute a system or arrangement much greater than, yet analogous to, the system or arrangement of a great factory. In the attempt to understand the laws of nature, which they illustrate and obey, let us avoid the confusion that inevitably attends beginning from the middle, by proceeding in the way suggested in our illustration -- the only scientific way.

These movements, so various in their modes, and so complex in their relations, with which political economy is concerned, evidently originate in the exertion of human will, prompted by desire; their means are the material and forces that nature offers to man and the natural laws which these obey; their end and aim the satisfaction of man's material desires. If we try to call to mind as many as we can of the different movements that are included in the production and distribution of wealth in modern civilization -- the catching and gathering, the separating and combining, the digging and planting, the baking and brewing, the weaving and dyeing, the sewing and washing, the sawing and planing, the melting and forging, the moving and transporting, the buying and selling -- we shall see that what they all aim to accomplish is some sort of change in the place, form or relation of the materials or forces supplied by nature so as better to satisfy human desire.

Thus the movements with which political economy is concerned are human actions, having for their aim the attainment of material satisfactions. And the laws that it is its province to discover are not the laws manifested in the existence of the materials and forces of nature that man thus utilizes, nor yet the laws which make possible their change in place, form or relation, but the laws of man's own nature, which affect his own actions in the endeavor to satisfy his desires by bringing about such changes.

The world, as it is apprehended by human reason, is by that reason resolvable, as we have seen, into three elements or factors -- spirit, matter and energy. But as these three ultimate elements are conjoined both in what we call man and in what we call nature, the world regarded from the standpoint of political economy has for its original elements, man and nature. Of these, the human element is the initiative or active factor -- that which begins or acts first. The natural element is the passive factor -- that which receives action and responds to it. From the interaction of these two proceed all with which political economy is concerned -- that is to say, all the changes that by man's agency may be wrought in the place, form or condition of material things so as better to fit them for the satisfaction of his desires.

Between the material things which come into existence through man's agency and those which come into existence through the agency of nature alone, the difference is as clear to human reason as the difference between a mountain and a pyramid, between what was on the shores of Lake Michigan when the caravels of Columbus first plowed the waters of the Caribbean Sea and the wondrous White City, beside which in 1893 the antitypes of those caravels, by gift of Spain, were moored. Yet it eludes our senses and can be apprehended only by reason.

Any one can distinguish at a glance, it may be said, between a pyramid and a mountain, or a city and a forest. But not by the senses uninterpreted by reason. The animals, whose senses are even keener than ours, seem incapable of making the distinction. In the actions of the most intelligent dog you will find no evidence that he recognizes any difference between a statue and a stone, a tobacconist's wooden Indian and the stump of a tree. And things are now manufactured and sold as to which it requires an expert to tell whether they are products of man or products of nature.

For the essential thing that in the last analysis distinguishes man from nature can, on the material plane that is cognizable by the senses, appear only in the garb and form of the material. Whatever man makes must have for its substance preexisting matter; whatever motion he exerts must be drawn from a preexisting stock of energy. Take away from man all that is contributed by external nature, all that belongs to the economic factor land, and you have, what? Something that is not tangible by the senses, yet which is the ultimate recipient and final cause of sensation; something which has no form or substance or direct power in or over the material world, but which is yet the originating impulse which utilizes motion to mold matter into forms it desires, and to which we must look for the origin of the pyramid, the caravel, the industrial palaces of Chicago and the myriad marvels they contained.

I do not wish to raise, or even to refer further than is necessary, to those deep problems of being and genesis where the light of reason seems to fail us and twilight deepens into dark. But we must grasp the thread at its beginning if we are to hope to work our way through a tangled skein. And into what fatal confusions those fall who do not begin at the beginning may be seen in current economic works, which treat capital as though it were the originator in production, labor as though it were a product, and land as though it were a mere agricultural instrument -- a something on which cattle are fed and wheat and cabbages raised.

We cannot really consider the beginning of things, so far as a true political economy is forced to concern itself with them, without seeing that when man came into the world the sum of energy was not increased nor that of matter added to; and that so it must be today. In all the changes that man brings about in the material world, he adds nothing to and subtracts nothing from the sum of matter and energy. He merely brings about changes in the place and relation of what already exists, and the first and always indispensable condition to his doing anything in the material world, and indeed to his very existence therein, is that of access to its material and forces.

So far as we can see, it is universally true that matter and energy are indestructible, and that the forms in which we apprehend them are but transmutations from forms they have held before; that the inorganic cannot of itself pass into the organic; that vegetable life can only come from vegetable life; animal life from animal life; and human life from human life. Notwithstanding all speculation on the subject, we have never yet been able to trace the origin of one well-defined species from another well-defined species. Yet the way in which we find the orders of existence superimposed and related, indicates to us design or thought -- a something of which we have the first glimpses only in man. Hence, while we may explain the world of which our senses tell us by a world of which our senses do not tell us, a world of what Plato vaguely called ideas, or what we vaguely speak of as spirit, yet we are compelled when we would seek for the beginning cause and still escape negation to posit a primary or all-causative idea or spirit, an all-producer or creator, for which our short word is God.

But to keep within what we do know. In man, conscious will -- that which feels, reasons, plans and contrives, in some way that we cannot understand -- is clothed in material form. Coming thus into control of some of the energy stored up in our physical bodies, and learning, as we may see in infancy, to govern arms, legs and a few other organs, this conscious will seeks through them to grasp matter and to set to work, in changing its place and form, other stores of energy. The steam-engine rushing along with its long train of coal or goods or passengers, is in all that is evident to our senses but a new form of what previously existed. Everything of it that we can see, hear, touch, taste, weigh, measure or subject to chemical tests, existed before man was. What has brought preexisting matter and motion to the shape, place and function of engine and train is that which, prisoned in the engineer's brain, grasps the throttle; the same thing that in the infant stretches for the moon, and in the child makes mud-pies. It is this conscious will seeking the gratification of its desires in the alteration of material forms that is the primary motive power, the active factor, in bringing about the relations with which political economy deals. And while, whatever be its origin, this will is in the world as we know it an original element, yet it can act only in certain ways, and is subject in that action to certain uniform sequences, which we term laws of nature.

Comments:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263