|

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

The Private-Investment Community Land Trust

A Better Way to Revitalize Communities

by Dan Sullivan

The essential concept

The private-investment community land trust is an alternative

system for private land-holding, for generating community revenues, and

for encouraging better land use. Essentially, land users lease the

land, rather than purchase it, from a land trust. The trust then uses

lease revenues to pay investors, to provide community services, to

rebate taxes levied against occupants of trust land by larger taxing

bodies, and to acquire additional land. It has many advantages over our

traditional land tenure system, and particularly over urban-renewal

projects, to the occupants, the investors, and the communities in which

they are located.

Current Occupants Can

Stay

Current Occupants Can

Stay

People often complain that urban redevelopment projects create

"gentrification," by which they mean pushing poorer people out in order

to entice richer people to move in. The land trust approach attracts

richer people and more dynamic businesses with little or no

displacement of those already living or doing business in the

community. Studies show that when a community gradually improves, it

actually loses fewer

residents than similar communities that stagnate

or continue to decline. The real cause of displacement is the urban

renewal project that is undertaken to trigger gentrification. Indeed,

the original term for "urban renewal" was

"slum clearance." The painting at left was of Ruch's Hill in

Pittsburgh's Hill District. No economic development followed, and the

land was eventually used for the Elmore Square housing projects, which

have also been torn down. Ironically, Elmore Square was to house people

displaced by other Urban Renewal projects.

The land trust model does not push

people out. To the contrary, it

invites landholders to sell their land to the trust and rent become

trust members on

the same terms that attract others to the neighborhood. They

also have the option of keeping their conventional land titles and

enjoying trust leaseholders as neighbors.

No Risky, Expensive Projects

The

track record of conventional urban renewal projects is

spotty, at best. Billions of dollars of public money have been spent on

failed projects. In Pittsburgh, the only major multi-building,

multi-owner projects that

could be called clear financial successes over the long term are Gateway

Center and Station

Square.

Parkway

Center Mall

(pictured at right) was successful for about two decades, but had been

built on a landfill and failed both structurally and economically. The

project

wasted a fortune in public money, not only on the mall itself, but on

an

interstate exit specially built to service the mall.

Allegheny

Center Mall

was an economic disaster almost immediately. The retail shops that were

supposed to serve surrounding residential developments quickly closed

and the spaces were eventually used as offices.

Penn

Circle,

which was supposed to revitalize East Liberty, saw one project disaster

after another, and quite literally became a textbook example of how not

to revitalize a community. It is only now beginning to succeed after

half a

century of failure.

Perhaps the biggest disaster, both

economically and socially, was the

clearance of the Lower Hill District beginning in the late 1950s that

forced thousands of people into housing projects and left much of the

land in limbo until the mid 1990s. The main project,

the Civic Arena, was torn down owing more money than what had been owed

when that hockey arena first opened. Three Rivers Stadium on the North

Side also had a much larger outstanding debt when it was torn down than

when it had first opened.

The land trust approach does not involve

projects. It simply creates

incentives that encourage ordinary people to take up land in the trust

and put it to better use.

No

Economic Cannibalism

No

Economic Cannibalism

Even the most successful renewal

projects destroy other

Pittsburgh businesses. They create new businesses that steal customers

from existing businesses, often without doing anything to increase the

overall market for these businesses. When the Grand Concourse opened at

Station

Square, it was ballyhooed by the Urban Redevelopment Authority, elected

officials and newspapers as the

place for seafood. As a result,

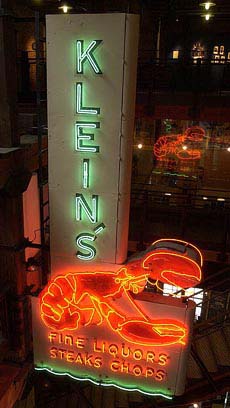

nationally famous Klein's

Seafood quietly went out of business. It had been such a Pittsburgh

landmark that its sign now hangs in the Heinz History Museum.

Businesses already pay higher tax rates in

the City of Pittsburgh than

in the suburbs. Part of their taxes go to subsidizing

their own competitors.

When the tax-subsidized East Liberty Home Depot opened in 2000, there

were eleven hardware stores within a 2.5 mile radius. By 2010, there

were none. Carpet stores, paint stores, plumbing and electrical

suppliers and other competitors also closed or moved out of the city.

The owners of these stores were driven out of business by the same city

to which they had taxes that were used against them.

Worse still, after Giant Eagle Supermarkets

got subsidies to build

large stores with parking in prime neighborhoods, they closed smaller

neighborhood stores in poorer neighborhoods. People do not buy more

groceries because we subsidize new grocers. Instead, we subsidized the

closing of small grocers and even of neighborhood Giant Eagles. This is

economic cannibalism - subsidizing new businesses to eat up the profits

of

existing businesses.

The land trust does not take money from some

businesses to

subsidize others. All tax advantages to businesses in the trust are

funded from land rents paid to the trust. Established businesses who

want these advantages can also sell their land to the trust and

enjoy the same incentives as other trust lessees.

No Eminent Domain

It is almost impossible to assemble

land for large-scale

development projects without resorting to eminent domain. Even Gateway

Center used eminent domain against more than 100 property owners. The

pattern is that small property owners who do not fight the takings in

court are poorly compensated, while those who conduct high-profile

campaigns are often given many times what the properties are worth.

Pittsburgh Wool won such a fight and was awarded $7.5 million for the

factory pictured at right, that had an estimated value of only $1.5

million. The settlement was heralded as a victory for property owners

everywhere, but other taxpayers had to cover a $6 million overcharge.

Although the land trust has more synergy if

it owns all the properties

in an area, it is not so important as to require the use of eminent

domain. Small property owners can join the trust or not, as they see

fit.

No Corporate Welfare

Development projects usually

involve massive subsidies to large corporate interests - from

construction firms to commercial occupants. Much of this is

unavoidable. Small independent business owners are usually too busy

tending to their own operations to even pay attention to

development-project opportunities. Large corporations, on the other

hand, have agents who specialize in negotiating deals with development

agencies.

The land trust approach involves no

subsidies. All tax advantages come

from rent revenues. People are encouraged to take individual properties

and put them to good use, which means ordinary businesses and residents

are on equal footing with large corporations.

No Insider Deals

Developers

like to keep their projects secret from those who

might buy land out from under them, from competing developers,

and even from community members who might organize against the project.

this secrecy compounds problems when public money is involved. Even

politicians who give lip-service to openness and transparency find that

the very nature of development projects prevents them putting together

deals in a transparent fashion. Local community organizations, who had

been promised that they would be part of the project planning process,

often find project plans handed to them as a fait accompli. The most

progressive developers will listen to community leaders, but will not

reveal tentative plans and negotiate along the way. This is not the

fault of particular developers or particular politicians, but is in the

very nature of large-scale developments.

The land trust, on the other hand, is open

from beginning to end. The

land trust proposal, the charter, the process for selling shares, the

lease agreements, the internal governance of the trust and all other

issues are completely open.

Idle Land Speculation Ended

Our

current tax system punishes good behavior with high taxes and rewards

idle speculation with low taxes. Wage taxes, sales taxes, income taxes,

business taxes and the building portion of the property tax all fall on

those who putting their land to good use and making the community more

dynamic. Each land speculator minimizes his taxes an maximizes

his profits by getting others to improve and operate their properties

while he sits back and watches the value go up. That is, he becomes an

enemy of the very revitalization he from which hopes to profit. If too

many speculators do this, the community deteriorates and everyone's

land loses value. That is, the idle speculator is even the enemy of

other idle speculators. Still, the last one to develop gains the most.

Urban renewal projects actually

Our

current tax system punishes good behavior with high taxes and rewards

idle speculation with low taxes. Wage taxes, sales taxes, income taxes,

business taxes and the building portion of the property tax all fall on

those who putting their land to good use and making the community more

dynamic. Each land speculator minimizes his taxes an maximizes

his profits by getting others to improve and operate their properties

while he sits back and watches the value go up. That is, he becomes an

enemy of the very revitalization he from which hopes to profit. If too

many speculators do this, the community deteriorates and everyone's

land loses value. That is, the idle speculator is even the enemy of

other idle speculators. Still, the last one to develop gains the most.

Urban renewal projects actually  encourage idle speculators to hold on in hope that the

redevelopment authority will bail them out.

encourage idle speculators to hold on in hope that the

redevelopment authority will bail them out.

The land trust reduces this. Every

leaseholder pays a fair

rent on the value of his land, and a large portion of the lease revenue

is used to rebate taxes on his improvements and on desirable

activities. Although one can speculate on shares of land trust itself,

the shareholders have no control over land use. Their only powers are

to demand that the terms of the trust be upheld and to bring additional

land into the trust.

All control of land-use decisions rests

with the Leaseholders

Association, the Occupants Association, and individual leaseholders.

The trust is designed so it is in everyone's interest to make the

community as dynamic as possible.

Healing communties, not replacing them.

Urban redevelopment projects are

like tissue transplants. They

cut out rotted parts of a community, along with the people who live in

them, and replace the rotted parts with entirely new properties. One of

the reasons these "property grafts" fail so often is that they do not

deal with the underlying problems, or with the bad incentive structure

that caused the communities to decline in the first place.

The land trust changes those incentives so the

trust community can heal

naturally. As with any healing, improvement is first seen at the edges

and the blighted area shrinks away.

Localized and Specialized Control

The trust divides power into three sets of

associations.

The

Shareholders Association represents those who have put up the

money to

make the trust possible, the Leasholders Association represents people

who have taken up leases, and the Occupants Association represents the

people who actually live and work on trust land. The Leaseholders and

Occupants Associations are further divided by neighborhood and by

residential occupancy and employee occupancy. (On-site business owners

and managers are included in the employee occupancy criteria.)

Amending the trust charter or changing

future leases requires that all

three associations concur. Other decisions may be made by one or two

associations alone.

The Shareholders Assocation and each

member thereof has standing to

demand that the trust be administered as prescribed in the charter.

This is very important, as similar trusts have violated their charters

by collecting as little rent as possible. Because nobody had standing

to demand that the charter be administered as prescribed, these trusts

failed to offer the promised rebates or to acquire new land, even when

excellent opportunities presented themselves. The Shareholders

Association also controls the fund for additional land purchases, and

can make such purchases on behalf of the trust.

Each community's Leaseholders Association and

Occupants Association

have joint jurisdiction over how their portion of the rent fund in

their community is allocated between capital improvements, operations

and tax-rebate incentives, except that the trust-wide associations

might

set minimum-rebate policies in order to advertise those policies, and

the Shareholders association might grant additional funds to particular

neighborhoods.

Until there are enough leaseholders and

occupants, representatives of

community groups and Community Development Corporations can perform

these functions. This puts initial control at the neighborhood level.

Customizable Incentives Promote

Local Priorities

The land trust does not rely on planning

and projects, but on

built-in, rent-funded incentives that attract the kinds of development

that the local communities want. Community groups and Community

Development Corporations can set up the incentives. Once the land is

leased, the lessees and occupants control the incentives and other

trust aspects themselves.

Where

the local trust village chooses to rebate taxes on employers and

employees, the best deal goes to the leaseholder with

the biggest payroll for the land he occupies. That means not only the

most employees, but the best-paid employees. Rebating mercantile and

sales taxes attracts the store owners who expect to have the highest

sales volumes. If

the community wants to attract the working poor, it can rebate a

portion of wage taxes on residents up to a particular income level,

such as rebating taxes on the first $20,000 of earned income tax. In

Pittsburgh, it might want to rebate the most regressive tax of all, the

$52 per capita tax on every employee at the job site.

If the trust wants to attract families

with children, it can

offer child care vouchers and education vouchers. These vouchers can be

cumulative so those who attend public schools can save them for

vocational schools or higher education. For every desired outcome,

there can be an

incentive system that promotes an outcome without resorting to hard

and vast rules that mandate that outcome.

Flexible land use

Even

the best-planned communities have run into problems as conditions

changed.

For example, Columbia, Maryland has been heralded as a quintessential

example of a well planned community. Yet as times changed, they found

that they had relied too much on physical planning and hadn't addressed

underlying economic dynamics. Serpentine roads that were all the

rage when the towns were planned in the 1960s have become problematic

as reliance on mass transit has become more important. Embedding houses

in

wooded lots, which was appropriate to the surrounding areas at the

time, has left Columbia more vulnerable to criminals from poorer

neighborhoods that have grown up around Columbia. Most of all,

these planned communities have not avoided the bad economic incentives

that have lead to blight generally. For example, The West Lake Village

Center, one of Columbia's planned shopping districts, (shown at right)

is now dependent on urban renewal projects for rehabilitation.

By using economic incentives instead of

relying on hard planning alone,

the trust avoids the pitfalls of planned communities. The incentives

lead naturally to good urban land use, reducing the need for even

conventional zoning.

Small Businesses Attracted

Small businesses employ more people on less land than big businesses. Rebates to wage taxes, or to employers' contributions to payroll taxes, are a better deal for small businesses than for big businesses. New small businesses are also more concerned about startup costs, and are happy to lease land rather than purchase land. In the same way, small home builders and struggling home buyers are drawn to the trust because it avoids land acquisition costs. It has the opposite effect of of redevelopment projects, which push out small struggling businesses to attract corporate chain stores.

The Rent Funds

Many commercial properties are built

on leased land.

Usually,

the leaseholder is entirely responsible for all taxes, for attracting

tenants, for providing amenities, and so on. The landlord pockets the

entire rent as a profit or dividend. This works well enough for

prime land, where there is no difficulty attracting tenants.

Many commercial properties are built

on leased land.

Usually,

the leaseholder is entirely responsible for all taxes, for attracting

tenants, for providing amenities, and so on. The landlord pockets the

entire rent as a profit or dividend. This works well enough for

prime land, where there is no difficulty attracting tenants.

However, the land trust model is

designed to create a synergistic

effect by attracting better tenants to poor neighborhoods where those

tenants would not commit to a conventional lease.

First of all, the land trust continues to pay

all taxes on the land

itself. Should the city or borough increase real estate tax rates, the

trust bears the entire increase on the value of land.

Second,

the trust sets aside a significant portion of the rent to rebate taxes

that fall on the leaseholder or his occupants. This is not merely a

rent discount, but an incentive to get the leaseholder and his

occupants to more fully use the land.

Second,

the trust sets aside a significant portion of the rent to rebate taxes

that fall on the leaseholder or his occupants. This is not merely a

rent discount, but an incentive to get the leaseholder and his

occupants to more fully use the land.

Third, the commitment to continually buy more

land and bring it into

the trust protects those who build today from being pushed out by those

who would build even more tomorrow and would bid up the rent to do so.

(Additional rent protections follow.)

This can only work for shareholders if the

result is not a zero-sum

game. That is, the stockholders hope to come out ahead with a smaller

share of a much larger pie. If it works well for occupants and

leaseholders, and if they make the most of the incentives by doing more

with less land, it will also work well for the shareholders.

In

ordinary circumstances, dedicating 30% of the rent to rebating taxes

should be enough to attract

people to the trust. In blighted areas, larger rebates would

probably be necessary to get things started.

In

ordinary circumstances, dedicating 30% of the rent to rebating taxes

should be enough to attract

people to the trust. In blighted areas, larger rebates would

probably be necessary to get things started.

The trust could specify a high-growth

incentive system for a specified

period of years, or until a specified goal is attained, and shift to a

good-growth system after that. However, such a change would have to be

written into the original charter. Once the charter is in place the

shareholders cannot unilaterally decrease the rent share that goes to

amenities and rebates.

A taxing jurisdiction might also give the

trust a better deal on vacant

properties held by that jurisdiction, contingent on the shareholders

taking smaller dividends and increasing the fund for amenities and

rebates. That way the taxing jurisdiction gets the development it

desires more quickly, and also gets most or all of the rebate revenue.

However, there is a point at which the trust ceases to be an

investment, and the shareholders are essentially purchasing stock for

charitable reasons. It is wise to set the divisions to maximize growth,

but also to guarantee adequate initial investments.

Rent Increase Protections

The trust

reassesses the rent annually using market data,

including bidding on any vacant lots. The lessees can be protected from

large increases, but only up to the rental value of their buildings.

For

example, say that the protected rent is a limited to a fixed increase

plus general inflation. But as the

land trust is likely to be very successful, land might go up by far

more than that. In the graph at right, the yellow area is the market

rent, the blue area is the protected rent, and the orange area shows

what happens when improvements do not warrant complete protection.

A vacant lot gets no protection unless it is

joined to an improved lot.

If the leaseholder makes significant improvements are in the future,

the rent returns to what is shown on the blue line.

An improved lot, or set of lots, is

protected as long as the value of

the improvements is greater than the value of the protection. Suppose,

for example, that the leaseholder parks a mobile home on one of the

lots. As long as the rental value of the mobile home exceeds the

difference between the protected rent and the market rent, he gets the

full protection. However, if rent protection exceeds the value of the

mobile home, he begins to pay higher rents (orange area). To remedy

this, he can build a more valuable structure, or even (zoning

permitting) put a second mobile home on the lot. Because the rent

would continue to climb, we recommend a that people erect high-value

permanent structures that take full advantage of the rebate incentives.

However, mobile homes and other temporary structures are good interim

uses of the land while people learn what is likely to become the best

long-term use of the land.

Better Internal Political Systems

The concept of a democratic republic

is that the people

deliberate and choose their leaders. However, modern democracy, which

is based on elections and majority rule, has become dominated more by

power struggles and propaganda bombardments than by deliberation.

The ancient Greeks didn't have elections.

Local decisions were made by

whoever showed up to vote on those decisions, and Senates of Greek

city-states were chosen by lottery. While this approach eliminated the

power struggles of political campaigns, they had other problems.

The meddlesome tended to show up most often to town councils, and

the Senates were made up of people who often just average or even below

average in their ability to govern.

A third form of democracy, somewhat similar to

the way Greeks choose

their Senators, is the jury system. We trust juries to decide who goes

to prison and who goes free, and sometimes who lives and who dies.

Ideally, juries are also chosen by lottery, although this has been

modified to eliminate jurors who have conflicts of interest.

We propose juries, not to run trust

operations directly, but to chose

the most talented, most dedicated, and most ethical leaders, to

oversee those leaders, and to propose and adopt changes to governing

documents. Juries select representatives for routine decision-making,

and

are only called to deliberate on policy measures. Juries are far more

resistant to special-interest

campaigning, and the meddlesome have no greater chance to serve on

juries than anyone else. Of course, those who are concerned or

knowledgeable can testify to the juries.

Jury service would be entirely voluntary, and

jurors should be paid

enough that at least 50% of those invited volunteer to serve.

Small Investors Favored

In an normal corporation, board

members are elected on the

basis of

one share, one vote. A single shareholder or a small number of

shareholders who have over 50% of the shares have absolute power over

the corporation. In contrast, the land trust uses a jury system to

select board members. The trust invites shareholders to serve on

Shareholders Association juries

by lottery. While each shareholder's chances of serving on such a jury

is proportionate to his number of shares, even the largest shareholder

can only have one seat on a jury. This creates a balance between large

and small shareholders that prevents large shareholders from dominating

the trust.

Also, while institutions (particularly

non-profits) are welcome to buy

shares, only real persons who own shares in their own names are invited

to

serve on shareholder juries.

Small Leaseholders Also Favored

Each leaseholder's chances of being invited on to a jury is also proportion to the rent paid for his leasehold or leaseholds. Family owned corporations may designate a family member to be eligible for jury service, but extended and publicly traded corporations are not represented.

Occupant Juries and representatives

Matters that affect

all occupants are composed of both residential and employment-based

occupants. Matters that pertain to residential or employment-based

occupants alone can be decided by their representatives alone.

Innovated from Successful Precedents

Endorsements from economists

The trust incentive system has been proven, both by taxing

jurisdictions that taxed land values instead of buildings, wages,

business activities, etc., and by actual trusts, a number of which were

formed at the turn of the last century. The essential concept dates all

the way back to John Locke, who noted that all taxes come out of land

rent anyhow, and that other taxes are so destructive that it is better,

even for the landowners, to pay the taxes directly than to try to make

their tenants pay:

It is in vain, in a country whose great fund is land, to hope to lay the publick charge of the government on any thing else; there at last it will terminate. The merchant (do what you can) will not bear it, the labourer cannot, and therefore the landholder must; and whether he were best to do it, by laying it directly where it will at last settle, or by letting it come to him by the sinking of his rents, which when they are once fallen, every one knows are not easily raised again, let him consider.

- John Locke "Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, and Raising the Value of Money."

Other

economists and economic philosophers have also endorsed raising public

revenue from land values throughout history, from classical liberals

like the French Physiocrats, Adam Smith, William Penn, Herbert Spencer,

Ben Franklin, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Jefferson and Tom Paine, to

modern economists including Nobel Laureates James Buchanan, Milton

Friedman, Franco Modigliani, Paul A. Samuelson, Herbert

A. Simon, Robert M. Solow, Joseph Stiglitz, James Tobin and William

Vickrey.

We have also seen the benefits of charging for land in hundreds of

taxing jurisdictions around the world, including many jurisdictions in

Pennsylvania.

Jurisdictions using land value tax

HOW THE PRIVATE INVESTMENT LAND TRUST OPERATES

The private investment land trust is created out of

a contractual agreement between an investors1 corporation, a

leaseholders1 association, and a non-profit community corporation. The

land is owned by the investors' corporation, but the deeds are held in

escrow to guarantee the security of the leaseholders and other

community residents.

An independent real estate appraiser determines the

fair market rent of each land parcel based on real estate statistics.

If the investors' corporation and the leaseholders1 association are

both satisfied with the quality of county tax assessments, they can be

used for determining rents.

Every four years, parcels are re-appraised, with

particular attention given to separating the value individual

improvements made by the leaseholders and residents from the value of

the parcels themselves.

Lease rents are determined by the unimproved values

of the parcels using a predetermined formula. Between appraisals, lease

rents are adjusted according to a general inflation index or by a land

price index for the area.

Leases are administered by an independent real

estate agent, or, if agreed upon, by a member of the community.

The rents are collected, and the costs of

administering the leases are deducted. Also, all property taxes

accruing to land values are deducted.

The remaining proceeds are divided according to an

established formula. A portion goes to the community corporation, a

portion to the investors1 corporation, and a portion into a fund for

future land purchases.

The funds allocated to the community corporation are

used first to pay property taxes on improvements owned by the community

and by community members. Additional revenues can be used to finance

community improvements and services. Any funds still remaining are used

to pay other taxes incurred by the tenants.

The portion sent to the investors' corporation is

distributed as dividends to the investors after necessary corporate

expenses have been paid.

The portion allocated for future land purchases is

put in a fund held jointly by the community corporation and the

investors' corporation. When both groups agree, the fund can be used to

purchase land adjacent to the community, which then becomes a part of

the community.

If the fund reaches an established limit and no

adjacent land purchases are agreed upon, the investors' corporation can

use the funds to purchase another tract of land elsewhere, where

another leaseholding community will be established.

Land for expansion can be acquired in other ways as

well. Additional investors can be invited to join the corporation and

be issued stock commensurate with the value of their investment. They

can invest with money, which is placed into the expansion fund, or with

suitable land, which becomes a part of the community upon being

invested in the corporation. Occupants of the land are offered priority

in taking leases.

ADVANTAGES TO THE LEASEHOLDER

There are several advantages which accrue to the

leaseholder. First of all, he does not have to make an initial purchase

to acquire land. His funds can be directed toward making property

improvements. He does have to pay a fair market rent, but this costs

far less than a mortgage on the land would cost.

Mortgage costs include interest plus "amortization"

of the purchase costs; land rent reflects interest value alone. Also,

the purchase price of land is artificially high due to the presence of

land speculators who bid up prices. However, leases of this type are

not attractive to speculators. Land rent, therefore, does not reflect

"speculative" value.

Although land rents will continue and gradually

increase, while mortgage payments end after thirty or forty years, the

most difficult financial period for most homeowners is while their

house is still being paid for. Being able to defer land payments by

leasing helps them get through this critical period. A leaseholder who

wants to make higher payments and have equity in his share of land in

the community can become an investor as well by purchasing stock in the

landholding corporation.

The leaseholder is just as secure in his lease as he

would be holding a deed. The leases are fully transferable, and the

rents are guaranteed not to exceed fair market value.

Conventional landowners can lose their property for

failure to pay any number of taxes imposed upon them -- taxes which can

be selective, arbitrary, and unfair. Some leases shield leaseholders

from discriminatory taxation, and are, therefore, better security than

a conventional deed. Under a tax-sheltering land lease system,

leaseholders can build homes, earn wages, etc., without being taxed for

these activities by local governments.

Also, leases are not subject to the deed transfer

tax, which, in Pennsylvania, takes two percent of the purchase price

from conventional property owners every time title is transferred.

Leaseholders can sell their property improvements and transfer their

leases without anyone having to pay transfer taxes.

The community corporation can and should co-endorse

home improvement and construction loans, since some banks are reluctant

to issue mortgages on leased property. However, more credit is

available to community-backed leaseholders than to conventional

landowners. The community corporation can even start a credit union for

improvement loans with revenues in the expansion fund. Such a policy

greatly increases the opportunity for leaseholders to acquire funds for

property improvements.

The leaseholder's biggest advantage is the assurance

that adjacent properties in the community will not become derelict.

Because land rent is collected by the community corporation, it is not

profitable to hold leased land out of use. Negligent absentee

landlordism is virtually non-existent in land-lease communities.

ADVANTAGES TO THE COMMUNITY

Advantages which accrue to responsible, energetic

leaseholders translate into advantages to the community and to all of

its members.

When the lease system and other considerations are

designed to create a particular set of advantages, the community

attracts people interested in those advantages. People who like a

particular kind of community will like a particular kind of lease, for

the lease provisions embody the essence of the community structure.

A lease system that gives advantages to

conscientious homeowners is not particularly attractive to exploitative

landlords or to demoralized and unambitious squatters. Even if such

people find their way into a leasehold community, it is likely that

they will either become productive community members or that they will

leave.

Because the land is not owned as separate parcels,

the community is not torn by conflicts of interest that arise between

private landowners. And because the land is leased, and property

improvements privately owned, the community does not have to depend on

rigid structures and strong leadership, which are often necessary in

communities where common ownership goes beyond ownership of land.

The land lease community does not have to resort to

taxation to pay for community improvements. This guarantee against

taxation makes the leases more attractive. Moreover, using land rents

for financing community improvements provides sound criteria for

judging whether an improvement is worthwhile: a worthwhile improvement

makes the community a more desirable place in which to live; a more

desirable community commands higher land values and, therefore, higher

rents. The increase in rents to the community fund automatically pays

for most economically sound community improvements. In fact,

leaseholders who benefit most from a community improvement pay the most

for it, as their benefits from the community are part of the basis of

their assessed rental obligations.

Because the community is run as a private

corporation and not as a municipality, it has greater flexibility than

local governments. It can be run by town meetings, elect officials

within the structure of its choice, and even choose leaders by lottery.

It can operate like a private condominium development, or it can take

on what are considered to be municipal functions. If revenues permit,

it can even provide for private education without interference from the

state.

The Fairhope Single Tax Colony, for example, created

the still thriving community of Fairhope, Alabama in 1894. Fairhope is

like any other municipality except that it has no taxes; all municipal

services being paid for out of lease revenues. Because all the property

in Fairhope is listed on a single deed, the corporation was able to

have all public utilities delivered directly to the corporation at

reduced rates available only to large users. The corporation is able,

therefore, to provide utility services to community residents at a

savings.

The amount of services a land-lease community can

provide for its members depends on how much revenue it collects, and on

what portion of that revenue is allocated for community services. But

the absence of idle speculation creates advantages in all land-lease

communities, even if they defray no taxes for the leaseholders and

allocate no revenues for community services.

ADVANTAGES TO INVESTORS

Investors in the community corporation are

essentially landowners who have pooled their resources and have given

up control over land use to the community and to the leaseholders.

Because they have invested their money, they are

entitled to dividends. As with any growth investment, dividends are

lower at first, but increase with the growth and development of the

community. If the lease agreements allocate a large portion of lease

revenues to the community fund and expansion fund, initial dividends

are even lower, but the growth of the community is faster, yielding

higher dividends in the future.

By owning shares in a community instead of parcels

within the community, investors know they will not be indifferent to

one another's desire for a return on investments. Stockholders in a

community have a natural harmony of interests, compared to the often

conflicting interests of investors in land parcels.

Private land speculators have a natural tendency to

want to see their neighbor's land developed first. By the same token,

anyone investing in land next to a speculator's land will find his

speculating neighbor to be a drag on community development. In a lease

community there is no such drag. Investors in such a community can be

confident that the community will grow smoothly and evenly.

In communities that shelter residents from property

tax and other taxes, community members are even more eager to improve

their properties, making the community grow even faster. In the long

run, this means higher returns to investors.

Investors can also transfer their holdings without

having to pay transfer taxes and without disrupting the lives of the

leaseholders.

Investing in a private community land trust is every

bit as sound as investing in land directly. In the long run it will pay

more; it is easier and more convenient to sell shares in the trust than

to sell real estate directly; and it is certainly more ethical and

prestigious to invest in a community land trust than to be a land

speculator.

The fact that the land trust is such a good deal for

leaseholders and residents makes it a better deal for long term

investment as well. Leases are accepted quickly, people tend to develop

their properties more fully, and as the community develops a reputation

for being a fine place in which to live, rental values automatically

increase.

OTHER ADVANTAGES

There is a growing number of people who believe in

the land trust concept as crucial to the vitality of social

development. If invited, many of these people would eagerly invest in a

land trust community like the one outlined above. Some people have even

expressed an interest in bequeathing portions of their estates for the

promotion of land trusts. Indeed, many land trust communities have been

at least partially funded by bequests of this kind.

Investment in the land trust does not have to be for

private gain. Investments can be made naming charities as

beneficiaries, and investments can be made by the charities themselves.

The community fund itself can be the beneficiary of investment

dividends, or dividends can be placed in the expansion fund.

The unique and progressive features of a

private-investment land trust community make it a suitable subject for

many alternative publications, and generate opportunities for free

publicity. Such publicity attracts potential investors as well as

potential leaseholders.

STARTING A LAND TRUST CORPORATION

Starting a land trust corporation requires careful

planning and sound legal judgment. Fortunately there are a number of

organizations interested in land trusts which can be helpful with

problems of designing leases, developing community structures, etc.

Also, there are existing land trust communities which can serve as

models for future communities.

Most land trusts are non-profit and have no

provision for expansion, and some are radically different from what is

outlined above. Still, information about these trusts can be helpful to

anyone starting a land trust community.

631 Melwood Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15213

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263