McNair Had A Purpose

|

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

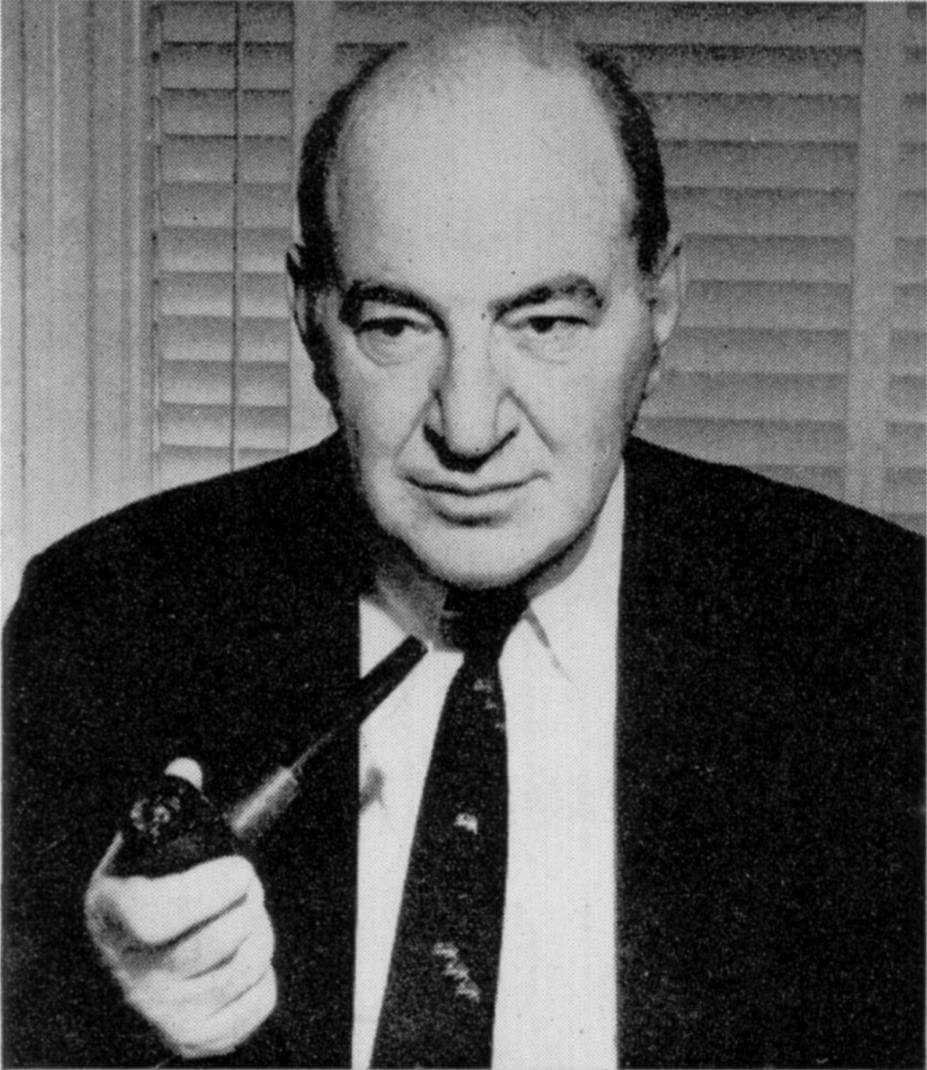

William N. McNair Had A PurposeAn Interview by Frank Chodorov, editor, The Freeman, July, 1940 |

"That's old stuff." Bill McNair has the philosophic attitude. His experiences have importance to himself, if at all, only objectively. Therefore, if you want him to talk about his three turbulent years as mayor of Pittsburgh you must indicate that your queries are not just gossip. If your purpose is in some way to advance the Georgist movement he will not hesitate to give you many details you did not expect.

I had heard that his sudden resignation from office in 1936 had its roots in a fight to force Pittsburgh land speculators to pay up delinquent taxes. But since this campaign, extending over his three years in office, was hardly reported by the press, not even in his own city, the story is known to only a few people. What is known about McNair, thanks to the newspapers, is that he ate apples in public, had himself arrested, played a fiddle very poorly, and generally behaved in a manner unbecoming the high office he held.

If his odd behavior had no purpose McNair might be considered a psychopathic case. Indeed, his political opponents had him trailed by brain specialists in the hope that some such charge might be brought against him. But to those who know McNair, and are familiar with his troubles in office, his antics did have a purpose.

For many years he had been running for office, any office, without hope of ever being elected, for the opportunity political action gave him to talk about the principles of Henry George. "I wanted an excuse for using a soap box," he explains. When the Roosevelt landslide in 1932 made him mayor, to the astonishment of everybody, mostly McNair, he continued his crusade. Also, he opened up the schools and other public buildings to the Henry George School of Social Science, which at one time conducted forty classes with an enrollment of a thousand students in Pittsburgh.

But, the public press completely ignored his Georgist speeches. That he came late to a public gathering was headlined; but the editorial blue pencil worked overtime on his references to the land question. Unless your knowledge came from other sources than the press you would never know that McNair had any social philosophy or fiscal policy.

The campaign of silence was on. A Pittsburgh newspaper man told me that editorial orders were to "lay off" McNair. But McNair was always "good copy" because he was always doing something a mayor shouldn't do. One day, for instance, he had himself arrested; that is, he insisted on the execution of a warrant obtained by his political opponents, who hoped he would follow the quiet procedure of putting up bail. Not McNair.

He called in a police officer, had himself taken to jail, sent for some apples and a copy of "Progress and Poverty," and proceeded to explain to his fellow jail-birds that they were not to blame for their predicament, but were the victims of a wrong economy. The arrest of a mayor is obviously front page news. But only one paper, in a small paragraph at the end of the story, mentioned his speech to the prisoners; and yet, that was why he had himself incarcerated.

His attempts to break through the conspiracy of silence failed. In the light of this failure one wonders whether his antics were ill-advised. But, hindsight is futile; and it is questionable whether any other method would have had more success in breaking into the landlord-controlled press. Judgment of McNair must be based on his unwavering adherence to principle, not on his methods.

"My troubles started when I started

something unheard of in Pittsburgh

How land speculators and their political henchmen operate when a fight on their privilege is precipitated is disclosed in the following incident.

"I aimed only at the big downtown tax dodgers, mainly because here was the greatest haul. Besides, the little fellow is rarely delinquent because the bank which holds his mortgage sees to it that he is not. The big landlord either has no mortgage or is not bothered about taxes by his bank.

"One day the newspapers, which hadn't given much attention to my tax-collecting campaign, came out with a story that I was squeezing the little home owner. I denied it. The next day they published the names of several small home owners against whom action had been started. Some clerk, evidently coached, had slipped these phonies into the pile of papers handed me to sign. The newspapers never mentioned the names of the downtown landlords I was really gunning for."

The collection of delinquent taxes was actually necessary to keep the city functioning. Each year the Council would appropriate a million dollars less than McNair needed to run the City; each year he would collect the million, and would have something over for the general funds. Which brings up a question: how much of our rent, even under the present inadequate system of taxation, is illegally retained by our landlords?

The politicians learned soon after McNair took office that he would not "play ball" and schemes to get him out of office began almost immediately. The incident which led to his resignation traces back to one of his first official acts. The political leader whom he had appointed City Treasurer was in the insurance business, and expected to act as broker for the city's insurance; the commissions totalled about $20,000. McNair wanted to give some of this business to an indigent henchman. The City Treasurer wanted all of it. So, McNair advertised that the insurance would be given to brokers who were delinquent in their city taxes. "In that way," he said, "some brokers who were in danger of losing their homes benefited, and the city got the revenue."

Under the law judgments obtained by the city for tax

delinquency are outlawed after five years, unless renewed

McNair discharged his treasurer. Thus the blame was legally placed where it properly belonged. But the City Council, which had fought the mayor throughout his term, refused to confirm any nomination he made. They wanted the same treasurer because, aside from being politically safe, he represented the legal means of getting rid of McNair.

A "ripper" bill designed to abolish the office of mayor in Pittsburgh had already been passed by the Pennsylvania legislature. McNair's term in office was therefore of doubtful duration anyway. The prospect of fighting a criminal action was distasteful. Without a City Treasurer bills and payrolls could not be met, and while the fight with the Council was going on the municipality was practically at a standstill. Bill McNair resigned.

"I found," he says, "that I had less chance to expound the theories of Henry George in office than when I was soap-boxing. The Georgist who thinks he can advance the cause as an office holder does not know that he cannot hold office unless he keeps his mouth shut. If he talks up it won't be long before he is out of office.

"That's probably as it should be. The politicians give the people what they want, if the people know what they want and are articulate about it. We cannot and should not expect land value taxation until enough people ask for it, and do so intelligently. The School is building that educable elite which brings about real reform always."

I asked him about the Pittsburgh Graded Tax Plan.

"All right as far as it goes, but it doesn't go far enough. Taxing buildings half as much as land has the tendency to encourage building. But rents in Pittsburgh are very high, indicating that the exemption of buildings simply raises the value of land. The speculators discount the exemption.

"Besides, unless the people know what he is trying to do, the man in office is helpless to effect permanent reforms. You can overcome the differential of the Graded Tax Plan by merely raising the building assessment."

And then, in his characteristically informal manner, he uttered a profound truth:

"You cannot change the folkway of the people overnight. Pittsburgh simply did not understand what I was trying to do. If we had had a few thousand graduates of the Henry George School who could have explained my purpose to their neighbors maybe I would have accomplished more."

Maybe McNair has had an effect on the folkway of Pittsburgh.

Comments:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263