The Subsidy Question

|

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

|

THE SUBSIDY QUESTION

|

The position taken by the Executive of the State has brought the question of railroad subsidies directly before the people of California. Either by express declaration or by silence, they must pass upon it as a matter of State policy at the general election this year.

And, again, at the Presidential election next year, if the Democratic party shall do its duty, the people must pass upon this same subsidy question in a still wider range, and as a matter of national policy.

It therefore behooves every citizen carefully and dispassionately to examine the subject in all its bearings.

The Question before the People.

Governor Haight's position is briefly this:

That the power of taxation delegated by the people to the State can only be exercised for public purposes.

That the exercise of the taxing power in order to subsidize private corporations is a misuse of the power, and an invasion of the reserved rights of individuals which cannot be legalized either by Act of the Legislature or by popular vote.

In support of this position, Governor Haight appeals to the declarations and spirit of our Constitution in reference to the rights of individuals, and contends, moreover, that the clause which prohibits the State from giving or loaning her credit to any individual, association or corporation, applies as well to the credit of the counties — that the whole State, not merely the State as a whole, is intended.

The weight of precedent is against him, for not only in our own State, but in every State in the Union, under Constitutions more or less resembling ours, have subsidies been given by counties and towns to railroad companies. He is supported, however, by recent decisions of great force and ability in several of the States, and by a rapidly increasing array of legal authority.

Whether he is right or wrong in claiming that our Constitution does prohibit railroad subsidies is not the question of first importance, nor the question which will come before the people for settlement. Whatever be the decision of the Supreme Court upon that point, to a higher power than Executive or Legislature or Supreme Court — to the people themselves, must be referred the larger question: Are railroad subsidies just and expedient? Shall they be permitted, or shall they be prohibited?

That Governor Haight has given his official sanction to subsidy bills — one of them, the Plumas bill, passed three years ago, of a most objectionable class — is a very strong argument against the infallibility of the man, but no argument against the justice of his present position nor even against his moral or intellectual integrity. If his present position is correct, his former acquiescence cannot rob him of the credit of being first on this coast to enunciate the true principle. In the language of the most eloquent of living Frenchmen: “The error of the beginning makes but worthier the truth of the end.”

Nor is the fact that the people have heretofore sanctioned the giving of railroad subsidies any reason why they should not now prohibit them. Consistency in error is not a virtue but a crime. If we can see now that we have been lured by promises of material advantage into doing that which was impolitic and wrong, duty and wisdom both call upon us to retrace our steps.

Whether railroad subsidies are constitutional or not may perhaps be an open question; but however that may be, leaving the lawyers to split hairs and quote precedents through interminable briefs, let us examine the broader question: Whether subsidies to railroad companies OUGHT to be constitutional?

Growth of the Railroad Power.

Perhaps the most important, and certainly the most difficult to solve, of the tremendous problems now pressing upon the American people, is the railroad question. Like the mighty Genius of Arabian story, the potent spirit loosed by Stevenson and Fulton swells and grows till the whole land is overshadowed by its presence, while upon its features the abject look of the willing slave is fast being lost in that of the imperious master. In the enormous corporations which the railroad system has crested — in the immense aggregations of capital which it has called into being, an imperial power is growing up within the republic that bids fair to become all dominating; a plutocracy is arising that promises to become more powerful than any the world has seen since the days when the dungeons of Roman patricians resounded with the groans of tortured debtors.

Beside these tremendous combinations (yet in their infancy) State power disappears, and even the Federal Government is dwarfed. In New Jersey a single and comparatively small railroad company has for years wielded absolute sway; the great State of Pennsylvania is literally governed from the office of the Pennsylvania Central; in New York, the Legislative power is a shuttlecock which Fisk tosses at Vanderbilt and Vanderbilt throws back at Fisk; in Massachusetts, a railroad company forces through the Legislature bills legalizing the most barefaced robbery of the people, and in New Hampshire another railroad company rules as completely as her two great cotton lords rule Rhode Island. In the West, the land-grant railways, with the land rings spawned by them, constitute the most potent political power; in the South, the piebald Legislatures, born of the reconstruction farce, but register the edicts of railway kings, and load the States with debts which must ultimately swamp them in bankruptcy; while in the metropolis a vulgar adventurer, who literally stole a railroad, boasts that he owns the entire judiciary, and in the capital of the nation railroad combinations force through Congress bills which give them fertile empires in fee simple without shadow of return or obligation.

It is no wonder that all over the country this railroad question is acquiring overweening importance. While our political system is showing signs of rapidly breaking down under the gathering weight of corruption that hangs to every wheel an festers round every pinion, the rapid rise and gigantic strides of this tremendous power may well awaken apprehension, and thoughtful men may well look around to see where the barriers that protect popular rights may be strengthened, and what new bulwarks may be thrown up against the advance of this all-absorbing, all-menacing force.

The recent declaration of a Western Senator, that the Government must soon own the railroads or the railroads would soon own the Government, was something more than a mere rhetorical flourish. It was in all seriousness that an Eastern writer, viewing the tremendous power of the railroad companies, and the all-engulfing corruption which their meddling in politics is engendering, proposed that we should resign ourselves to the inevitable, and give all power into their hands, on the ground that while they would then govern no more than now, they would do it by less demoralizing means.

And certainly, in view of the tremendous power which these railroad companies are acquiring; in view of the enormous influence which they are capable of exerting on legislation, it becomes us to examine very closely every pretext which may give them an excuse for interference in our politics, and to guard with scrupulous care every power of government which they may seek to use for their aggrandizement. Do what we may, the very existence of these gigantic corporations is a menace to republican institutions.

The Injustice of Railroad Subsidies.

There is at the first blush something so unjust, so repugnant to all republican principle, in using public money to set up individuals in business, that the wonder is how we came to consent to the practice at all. We hold to the doctrine of equal rights and privileges; but this doctrine is mocked when we give a manufacturing company the right to compel the people to pay three cents more on every spool of cotton they use; or when we take by taxation the money of the whole people and give it to two or three individuals, that they may build themselves a railroad. All the subtle distinctions that are made between public uses and private uses cannot hide the fact that a subsidized railroad, though built entirely by the people's money, as many of our railroads have been, is as essentially the property of its owners and managers as is the plow of the farmer, the tools of the mechanic, the wagon of the teamster, or the mill of the manufacturer. It has its public use, of course, just as the stage coach or freight wagon, the hotel or theater, have their public uses. Like these, it is an instrument whereby certain persons seek to make money, and like these it can only be used by those who can pay for its use. And if the people are to build a railroad for one man, why should they not be taxed to build a hotel or a theater for another, to buy a freighting team for a third, or supply a fourth with the tools he may want to use? By what principle is it that all the favors of the State are to be lavished upon one set of men? Certainly not a republican principle. That requires that all should be dealt with alike — either that all should be permitted to establish themselves in business with public money, or that none should.

But it will be said: “Although in subsidizing these railroad companies we do enrich individuals with the money of the people, we at the same time enrich the whole community. Railroads stimulate the settlement of the country, add to population and business, and increase the value of all adjoining property.”

But no one will contend that railroads benefit all alike. In fact, there are numbers of men in every community to whom railroads can be of no possible benefit. Is it not injustice to tax these men for the benefit of others? And admitting all that is is said of the benefits of railroads to the community as a whole, do not all industrial enterprises according to their degree accomplish the same result?

Does not the building of a mill or a manufactory add to the population, the business, the wealth of a community? Does not the erection of a fine dwelling house or store also add to the value of adjoining property? And are there not some enterprises which might have a greater effect in this direction than even the building of railroads? Supposing the city of San Francisco, instead of giving a million dollars towards the building of a railroad, were to give a million dollars towards the establishment of manufactories. Would not the promise of increase to business and wealth be as great in one case is in the other? In fact, would it not be greater? For is it not true that $100,000 invested in a manufactory will give direct employment to more people than $100,000 invested in a railroad? Or, supposing that an agricultural county, instead of paying one-half or one-fourth the cost of a railroad were to pay one-half or one-fourth the cost of his tools and necessary outfit to every farmer who would come there and settle; or that a mining county, instead of helping build railroads were to help build ditches, would it not lead to a more rapid settlement and far greater increase of taxable wealth than the same amount of money given as a bonus to a railroad company? It will be said that the building of railroads will induce settlement and cause the establishment of manufactories. But will not the establishment of manufactories and the settlement of the country also bring railroads? And is not this the natural, and therefore the most feasible order of development? Certainly, for every man who aspires to own a railroad, there are thousands who would like to be set up in smaller businesses, which, in proportion to the money involved, would be of as much incidental benefit. Is it not injustice to favor one small class of men to the exclusion of all others?

The Economic Aspect of the Question.

Leaving the question of justice aside, if the economic principle upon which we subsidize railroads is a correct one, should we not extend that principle to agriculture and manufactures — in fact, to every business that promises incidental benefit to the community, which would include almost everything from the making of shoe-pegs to the building of locomotives or the opening of mines?

This is an evident reductio ad absurdum. Any one can see that this would be bad policy, even were it possible. Yet the economic reason why we should not subsidize all businesses is the reason why we should not subsidize any of them. That reason is, that individual interest can be best relied on to apply the capital and labor of the community to the best advantage; or, to put it in another form, that each man is the best judge of what he should do and how he should do it.

Were we to attempt to subsidize everything that would be of incidental benefit to the community, taxation would become so high that no unsubsidized enterprize would be possible. Of course, the whole system would break down in irretrievable ruin long before we got to the point of subsidizing everything; but it might reach a point where the whole working capital of the community would be taken up in taxes, to be paid out in subsidies — minus the necessary loss in collecting and disbursing. What would be the result? The most unparalleled waste and extravagance. The sure test of the profitableness of every enterprise would be lost, and capital and labor be wasted on schemes which could only make the community poorer. Instead of individual interest directing individual effort, and each man, by employing his capital and labor to the best advantage, doing his utmost to add to the wealth of all, we would have the employment of capital and labor diverted by Act of Legislature everybody's business prescribed by everybody else. Our energies would be expended not in securing the largest and most economical production, but in making the biggest grabs at the treasury. The successful man would be, not he who best managed his own business, but he who secured the largest subsidy. What sort of a community would such a one be? Why, even leaving out of sight the overwhelming corruption that would quickly swallow everything, we would, if it were possible to approximate to such a condition of things, soon become the poorest people on the face of the globe.

This would be the result did we attempt to carry out the subsidy system to its fullest extent, and this is the result to which every employment of the subsidy system tends. For it must always he remembered that the State has no purse of Fortunatus to draw upon. The capital of the State is the capital of its citizens; the treasury of the State is the pockets of its people. Where one enterprise is encouraged by the gift of money, every other enterprise is discouraged by the increased taxation involved. We may establish a railroad or a manufactory by giving its projectors the necessary capital; but in doing so we lessen the capital of every producer and projector upon whom taxation falls. And whether the establishment of the railroad or manufactory is really a gain or a loss to the community, depends upon the fact whether the capital thus applied is more or less fruitful than it would be if left in its former occupations. As a general rule, it may be asserted that it would be less fruitful.

Delusion as to the Benefits caused by Subsidies.

Could we drain the land completely of its moisture, we might

produce a big river where none before existed, even in the summer time.

But would not this water, permeating the soil in invisible particles,

nourishing the grain of valley and the grass of hillside, be infinitely

more valuable than when gathered in a great river and rolling to the

sea, even though it then might give passage to huge ships and turn the

wheels of clattering mills? And so it is with capital. As a rule,

almost invariable, it is never so productive, because never so well

applied as when left in the hands of the workers of the community.

It is frequently difficult, without some thought, to distinguish the apparent from the real. We may see and hear the river, but the moisture in the soil is invisible to our eyes. From this difficulty spring the fallacies which support the subsidy, or as it is called when indirectly applied, the protective system. The Pennsylvanian sees the glare of the tariff-nurtured furnace, the cottages of its workmen, the lordly mansion of its owner, and he concludes that high duties are really enriching the country, for he cannot so readily see how from the Lakes to the Gulf, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, every work requiring iron — from the fastening of a shingle to the building of a steamship — is hampered and retarded by the same tariff.

We have in California vast deposits of low-grade ores, which, at the present value of capital and labor and the present cost of machinery, it will not pay to work. Supposing State or county were to give a bonus for the working, on a large scale, of one of these mines. A busy scene would take the place of the present solitude. Hundreds of men would be employed, a little town would rise, property around would increase in value, and it would be said: “See what wealth the judicious application of the public money has created.” But would there be really any creation of wealth? Would not the loss on each ton of ore mined still be the same, though by the subsidy it might be made to fall upon the whole community instead of individuals? Would not the State as a whole or the county as a whole be poorer than if the capital used had been left to seek occupations that would pay of themselves, instead of being coaxed into an occupation which of itself would not yield an adequate return?

Building Railroads Too Fast.

We may make the same mistake as to railroads. Railroads are undoubtedly a good thing; but we can certainly build railroads too fast. Where large amounts are to be transported, a railroad is undeniably the cheapest method of transportation; but where the amount to be transported is small it is by far the most costly, and to build a railroad for a traffic that will not justify the expenditure is extravagance of the same kind as would be shown in the erection of a steam mill for the purpose of supplying a single family with four, or the purchase of a ten-cylinder Hoe press for the purpose of working the four or five hundred edition of a country newspaper. And where a railroad is built before population — existing or immediately prospective — will justify it, the direct loss to the community may be hidden, but it can neither be compensated for by subsidies nor offset by the speculative rise of property. So long as a road will not pay the ordinary return on the capital invested, there must be a loss, which when supplied by a subsidy is only shifted from the shoulders of individuals to those of the whole community. Let us not forget that no Act of Legislature, no county vote, can create capital: only labor can do that. Capital will of itself seek the most remunerative occupations, and if by taxation we take capital from occupations which it does seek as remunerative, to put it in occupations which it does not seek, because not as remunerative, we can only net a loss. So, too, in borrowing we must pay a quid pro quo; and in the case of railroad subsidies, when we come to compare the net amount which really goes to help build railroads with the gross amount annually taken from the people by the tax-gatherer to pay interest, it will probably be found that the price paid is much more than even the productiveness of California will warrant.

There is such a thing as the overstimulation of railroad building. We may build railroads faster than population will justify or the capital of the community will warrant; and it is to this result that the subsidy system tends. And then, to offset the beneficial effects of the roads, we will have huge debts fastened on the community, and a rate of taxation which will repel settlement and depress industry. There are numbers of counties in the Western States which have bankrupted themselves by voting subsidies to railroad companies, some of them (if we may believe the statements of such papers as the Chicago Tribune) where the interest must be collected by legal process, and in which the value of all the property will not sell at Sheriff's sale for enough to pay the principal of the railroad bonds when they become due. To hear the advocates of railroad subsidies, one would imagine that it was impossible for a community to tax itself too much to build railroads — that the more it taxed itself for this purpose the richer it would be. But experience does not bear them out, as the people of Placer, of El Dorado and of Los Angeles have found to their sorrow; as the people of the great railroad State of Illinois — who adopted last year, by almost unanimous vote, a Constitution prohibiting any subsidy to railroad company by State or county or town — have discovered; as was found by the people of Pennsylvania thirteen years ago, when they embodied their experience, after incurring some twelve millions of debt, in a similar provision. In Pennsylvania, New York and Illinois, in Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin, high authority has declared that had the people never saddled themselves with debts for railroad subsidies they would have had the same or nearly the same amount of railroad as now, with much lighter taxation. And the same rule will hold true in this State. Had the programme of the railroad company four years ago been carried out, and the State compelled to pay $5,000 per mile for every mile of railroad built, how many more miles of railroad than we now have does any one suppose we would have had? And how much larger would be our debt? and how much higher our taxation?

The True Economic Principle.

We may safely lay it down as an economic principle, that where a railroad is really needed, it will be built without subsidies — be built by the operation of that law of self-interest which sends capital into every quarter of the world for profitable in vestment. And the converse of this is true: That where it will not pay private capitalists to build a railroad, it will not pay State, county or city to induce them to do so by the grant of subsidies — that the community will grow rich faster by leaving development to proceed in natural and symmetrical proportion than by attempting to force it in this or that direction; and that capital and labor will never be so productive as when left free to follow the natural laws which direct their application. This, too, is the principle of justice as between man and man. Where it is adhered to, all citizens are placed on an equal footing — no one is granted privileges which are denied to others, and no one is taxed for the benefit of another.

Popular Exaggerations of the Benefit of Railroads.

And without underrating the immense advantage of railroads — the gain of celerity, certainty, ease and cheapness of transportation — it may well be doubted whether their effects in developing and enriching the country have not been exaggerated. Certainly in California the extravagant anticipations with which we hailed the railroad era have not been realized. Population has not poured into our State, nor has our general prosperity seemed to increase. Nor in the United States at large has the increase of population during the last thirty-nine years, during which we have built nearly fifty thousand miles of railroad, been in any greater ratio than during the previous forty-one years when we built no railroads at all. The remarkable tables made by Mr. Elkanah Wilson in 1815, before railroads were dreamed of, and in which the population of the United States for a century ahead was predicted, still hold good — the census of last year, as all those preceding, showing that he correctly estimated the round numbers of our population at each decade. That railroads have greatly changed the distribution of population there can be no doubt — concentrating at some points, though dispersing over large areas; building up some great cities, though killing off the little villages and scattering the agricultural population; but that they have absolutely increased population these figures certainly do not show. Had our railroad system not been pushed so fast, the buffalo might yet have ranged over lowa, and Wisconsin still be unsettled, but there would be less uncultivated land in Ohio and Illinois.

And so, too, with the creation of wealth by railroads, of which we hear so much. A careful investigation would probably show that the effect of stimulating railroad building by subsidies has done more to alter the distribution than actually to increase wealth. It is certain that the economy in transportation effected by railroads has been to a very considerable extent offset by the increased transportation rendered necessary by the dispersion of population caused by the land speculation, which has gone hand in hand with railroad extension, while the increase in the value of the land, which constitutes the greater part of the apparent increase in wealth, can only in small degree be considered any actual increase in wealth. The State is not a whit the richer because uncultivated land formerly held at one dollar per acre is now held at ten. Whether a hundred vara sand hill in San Francisco is quoted at ten cents or $10,000 per front foot, makes no difference in the sum total of the real wealth of the city. The price may indicate the greater or less wealth of the community, the greater or less pressure of population, the greater or less availability and capability of the land itself. But in the latter case, which is the only case of real increase of value, this increased value is not available until the land is actually put to use. For instance: I own a tract of agricultural land which is increased in value by the construction of a railroad; I may sell it now for more than before; but the wealth of the community is not increased until somebody begins to cultivate it and really reaps the new advantage, whatever it may be. If I sell it, I shall be richer; but just what advantage I gain the buyer parts with, and we are both included in the community, whose aggregate wealth is unaltered by the transaction.

The Practical Workings of the Subsidy System.

Yet whatever be our opinion of the abstract justice and policy of subsidizing railroads, when we come to look at the practical workings of the system we can have no doubt of the necessity of putting an end to it. If the money given in railroad subsidies were honestly applied to the building of the roads there would be — to say the very least, rave doubts of the policy of ever granting subsidies. But as railroad building is now carried on, only a small portion of the money taken from the taxpayers really goes to the building of the roads. The privilege of spending other people's money has produced its inevitable consequences — extravagance, waste and rascality. The builders of subsidized roads expect to make fortunes in building them; not only to get the railroad itself for nothing, but to be made rich for their condescension in taking the gift. Their investment is generally just enough to carry through the preliminary operations of lobbying and electioneering for subsidy; and then, after all the subsidy that can be had in the shape of lands, bonds, money and privileges, is wrung from Federal Government, State, counties, cities and towns, mortgage bonds upon the road are issued and sold; John Doe and Robert Roe, the Directors, give a contract for building the road at an exorbitant price to the firm of Roe & Doe; and by the time the road is finished, Messrs. John Doe and Robert Roe have made fortunes and are looking about for another chance to develop the resources of their country in the same way, while the road itself is saddled with a large debt, for the interest upon which, and for the profit of its managers, its traffic must be forced to pay extortionate prices.

If the public, who really furnish all the capital invested in these roads — and, as a general thing, a good deal more besides — got any consideration in return for their bounty, the thing would not be so bad. But they get none at all. Is there a subsidized road in the United States on which the charges upon transportation are less than they would have been had the road been constructed with private capital? In fact, the reverse is more frequently the case; for, where a road is built by private capital, the interest of its builders is to make it cost as little as possible; but where it is built by subsidies the interest of its builders is to make it cost as much as possible, and the very amount of its stock and bonded indebtedness, a large portion of which represents not the real cost of the road, but the stealings — no (that word is only for small amounts ), the “enterprise” of its constructors, is made an excuse for keeping up charges. There is not, it is safe to say, a subsidized road in the whole Union which has not been made to cost a great deal more than the same road would have cost had it been built by private funds, and in the case of many of them the comparison between the nominal cost and the actual cost is absolutely ridiculous.

A Sample Operation in Railroad Building.

How the Pacific roads were built is pretty generally understood — how the Directors of the Union Pacific contracted with themselves under the title of the Credit Mobilier, and how the Directors of the Central Pacific contracted with themselves under the title, first, of Charles Crocker & Co., and afterwards of the “Contract Company;” how the Sierra was moved down to Sacramento, and the construction was inspected through champagne glasses; but the approved method of building subsidized railroads has recently been so well exemplified on a small scale in the southern part of our State that it is worth while to summarise the history of the operation, which is to be found at length in the printed reports of the Common Council of Los Angeles:

In November, 1867, thirteen citizens of Los Angeles associated themselves to build an eighteen-mile railroad from Los Angeles to the Bay of San Pedro, under the title of the “Los Angeles and San Pedro Railroad Company.” The capital stock was fixed at $500,000, each of the original thirteen subscribing $2,500 in gold coin. It does not seem that any of these stockholders paid in a single cent, though some of them advanced a little money for printing, advertising, lobbying at Sacramento, etc.

Why should they have paid in a cent? Their object was to own a railroad, not to pay for one, and to own a railroad now-a-days it is not at all necessary to pay for one; all that is necessary to do is to get the people to pay for building it for you. So these gentlemen, instead of putting in their own money, went to Sacramento, where the Legislature was in session, and got through a bill authorizing the city of Los Angeles to subscribe $75,000 to their stock, and the county of Los Angeles to subscribe $150,000. Both city and county voted to subscribe, for it was proved to the people very clearly by the advocates of the road, not only that it would cause a great increase of taxable property, and all that sort of thing, but that they would not be called upon to pay the interest on the bonds, as the road could not fail to pay, and the dividends accruing on the stock of the city and county were to be paid into a fund to meet the interest on the bonds.

So our railroad builders, the Directors of the Los Angeles and San Pedro Railroad Company, went to work. Not one cent had been paid in, but their first act was to divide among themselves $14,500, as recompense for the money they claimed to have spent in starting their little ball a-rolling. There being no money in the treasury, they could not pay themselves in cash, so they credited themselves with this amount on the books, and left it to bear interest. The next thing to do was to let a contract for building the road. And now Phineas Banning appears on the scene, though it is probable that he had been behind the scenes from the beginning. The law under which the city and county subscription had been made called for a railroad from Los Angeles to San Pedro, but, without regarding the law, the Directors decided to build the road to Wilmington, instead of San Pedro, as at the former place Mr. Banning owned land, a wharf, a hotel, and some other traps. The bids came in — the lowest, from a Mr. Ives, being for $342,000; the highest, from Mr. Phineas Banning, being for $467,000. Of course Mr. Banning got the contract, for it is an invariable rule with railroads to be built by the people’s money that the highest bidder gets the contract. Having let this contract, the next step of the Directors was to buy a piece of land and a lot of lighters and other things that Mr. Banning had lying around his town of Wilmington, for the sum of $70,000. Then these Directors mortgaged the whole road, all its property and franchises, and issued first mortgage bonds to the amount of $300,000 to help pay Mr. Banning. And the building of the road commenced, and the city and the county were called upon to issue their bonds, and did issue them, though none of the other stockholders paid in a cent; and before the road had been completed Mr. Banning had all the county bonds and all the first mortgage bonds, and his partner had all the stock, and things went along beautifully. Whenever a section of the road was completed and ready for acceptance, the engineer was discharged, so that there was no one to say whether it was well or ill built; and Mr. Banning, who had learned as he went along, and discovered that he had not been as enterprising at the start as he ought to have been, and had not made his bid high enough, put in large claims for extras, which were invariably allowed, and did various other things which showed him to be a great railroad financier, but which are too numerous here to mention.

And now the people of Los Angeles have got a little one-horse local road, which their money and nobody’s else has built, for riding on which they must pay is much as they used to pay the stages. And they have a debt of $225,000, the interest of which they have to pay every year, and the principal of which it is certain they must ultimately pay. How to relieve themselves they don't know, unless they can repudiate the whole thing. They can’t sell their stock, for the road is heavily mortgaged, and they fear they can’t assess the other stockholders, who have never paid anything, without assessing themselves. It is unnecessary to say that the people of Los Angeles believe in the doctrine laid down in Governor Haight’s letters, and are not in favor of any more railroad subsidies — all except Mr. Phineas Banning, who thinks Governor Haight is an enemy to the development of his country.

This is but a fair sample of the manner in which railroad building, under the subsidy system, is now conducted in the United States, and instances just as bad could be multiplied from every State in the Union where the subsidy system has prevailed. To dignify such proceedings with the title of “enterprise” — to style the system that begets them the “encouragement of internal improvements,” is as bad a misuse of words as to call the operations of “road agents” honest industry. It is not railroad building which we are encouraging, but public robbery! It not the investment of capital in remunerative pursuits which we are stimulating, but the swindling of our governments and the oppression of our people!

The Length to which the Subsidy System has been carried.

Why! look at the point which this subsidy business has reached! We are not only asked to help individuals to build themselves railroads, but to build railroads for them outright; not merely to do this, but to give them large bonuses besides; and we have been asked, and we have given, not merely enough to build the road and leave a profit besides, but enough to build the road four, five and even ten times over. And on the road thus paid for over and over again, neither individual citizens nor the State will have a single right, concession or privilege which they or it would not have on a road built and equipped entirely by private means!

It is not legitimate enterprise we are encouraging, but hordes of vultures we are calling into life — vultures who will not leave the carcass while a shred of flesh is left upon the bones. Give one subsidy, and it is used to extort another! Give one subsidy, and the road is not built until every cent of subsidy that can be squeezed out in had; till individuals have bid their utmost for the location of stations, and rival towns for the location of depots. Look at the Western Pacific, after obtaining more from Congress than would build it, exacting a subsidy from every county through which it passes, from the State and from San Francisco, and from Oakland its whole water front. Look at the Southern Pacific, after holding for six years a grant of between six and seven million acres of good land, worth more at present prices than would build and stock the road, debarring settlers all this time from all that fertile domain, and holding besides a grant of thirty acres in Mission Bay, worth at the lowest estimate a million and a half more; owned, too, by men who have received the more than imperial bounty showered upon the Central and Western Pacific roads — look at this road, with all these endowments, lobbying a bill through the last Legislature to compel some of the counties to pay it more than the assessed value of their entire property, and then demanding of the city of San Francisco a million besides, and, being refused in that demand, stooping to rob the city by what should be the highest crime known in a republic — stuffing the ballot-box.

Look at the Northern Pacific Railway, asking for subsidy to help construct a road, and getting from Congress the grant of enough fertile land to pay for its building and more. Coming back again, without striking a pick or felling a tree, and getting an extension of time; coming back again with another demand and getting it; coming back still again, with all the force of the wealth which the previous grants gave, and forcing through, in spite of the opposition of such men as CASSERLY and THURMAN (who, to their honor be it said, stood out to the last against the iniquity): forcing through, by the power of bribery and log-rolling, a bill which has no parallel in the history of franchises — a bill which gives them in fee simple, without condition or reservation, more land than would make a dozen great States; which gives them a property worth four or five hundred millions for building a road which will cost forty or fifty millions, and which road, when built, will be completely their own, neither the United States nor any of their citizens having upon it the slightest right or concession that they would not have on any private road. Nor would we be safe in predicting that the Northern Pacific is done yet. If it does not come back to Congress for more land, it will probably demand further subsidies for itself or for its branches from each of the new States through which it will pass. And it will have the power to get them, too; for from the Lakes to the Pacific it will absolutely rule each State and Territory.

How Subsidies discourage Railroad Building.

All this public robbery is perpetrated under the plea of encouraging railroads, yet it may well be doubted whether after all the subsidy system has not done more to discourage than to encourage railroad building. The extravagance, waste and rascality to which it has given rise have taken railroad building out of the list of profitable investments. Who but a fool would invest his money in the stock of any subsidized railroad company with the expectation of return, unless he belonged to the managing ring? And yet there is hardly a railroad in the United States, subsidized or unsubsidized, which, if honestly managed, would not pay dividends upon the real amount of its cost. If our roads were honestly built and honestly run, there is enough capital in the United States seeking remunerative investment to build all the railroads we want, while we would get better service, and at the same time be relieved from the burdensome taxes which these subsidies impose upon us — taxes which discourage all enterprise.

The great land grants, too, in the long run undoubtedly discourage railroad building. Though in some cases these grants may hasten by a few years the building of a trunk line, yet their beneficial influence stops here, and their secondary effect is to retard railroad building — to retard it by barring out settlers by the advanced prices of land, and by the building up of great landed and moneyed corporations, who from interest will oppose and in most cases prevent anything like competition. And frequently the primary effect of these land grants is to discourage railroad building. Had the land in Southern California which for six years has been withheld from settlement by the Southern Pacific grant, been open to those who wished to cultivate it, that country would have been much more largely populated, and private capital would ere now have had a road well on its way to Los Angeles.

Nothing can exceed the ruthless, stupid wickedness with which we are making away with our public lands, under the specious plea of “developing the country.” For anything which can serve as a parallel we must go back to the days of the Norman conquerors and their forest laws. But we sin against the light. We can see the centuries of misery which land monopolization has caused in other countries; we know, or ought to know, that everything in American character or in American institutions, of which we are justly proud, can be traced to the cheapness of land, yet we are giving away our priceless heritage, the public domain, in fifty-million-acre tracts, and our whole policy seems founded upon the idea that the quicker we can make land dear the better it will be. Within the last decade we have given nearly two hundred million acres of land to railroad companies alone, besides granting it away on almost every other conceivable pretext, and offering every opportunity for individual monopolization. The public land fit for cultivation now left us does not amount to fifteen acres per capita. Yet our population is increasing at the rate of thirty-five per cent. each decade, and in thirty years will reach one hundred millions! Do our people appreciate the tremendous meaning of these simple facts?

The Necessity of Prohibiting All Subsidies.

But we are told that for all the robbery and rascality perpetrated under the cover of subsidies, there are still cases in which it is advisable to give moderate subsidies under proper restrictions; and that, instead of opposing all subsidies, we should only oppose extravagant and unnecessary ones.

Ignoring all that may be said of the essential injustice and inexpediency of all subsidies — admitting, for the sake of the argument, that there may be conjunctures in which it might be advisable for a county or the State to give a moderate subsidy, how is it possible to prevent the abuse of subsidies except by prohibiting them in toto? To open the door for one, opens the door for all. If we would shut out any, we must shut out every one.

When we consider the tremendous energies of the railroad power now arising all over the country, the ease with which it manipulates Conventions, manages Legislatures, gags the press, carries elections, and even controls the bench, the necessity of prohibiting all subsidies becomes apparent. If we do not positively and decidedly take a stand against all railroad subsidies; if we do not engraft the prohibition upon our fundamental law, as have the people of Illinois; if we do not make opposition to them a party tenet, we cannot protect ourselves against the abuse of the power and the robbery of the people. The history of our own State, and of every State in the Union, proves that Legislatures are like wax in the hands of a great railway corporation, after its power becomes well organized. Nor will the ordeal of elections, though fair enough in appearance, really suffice to protect the people. In every case in which we put a subsidy proposition to vote, we are pitting direct moneyed interest against that shadowy thing, the public good. On the one side is a compact and powerful organization, which has a hundred thousand or a million of dollars, as the case may be, to gain by carrying the proposition, while on the other side, though everybody is interested, nobody is so particularly interested that he can afford to spend money or devote much time to the matter. It is like pitting a small army against a large mob, and the popular feeling must be strong indeed if the side which has the money to gain does not come off victorious. In a sparsely-settled county, where a question of subsidy is to come before the people, a large gang of workmen can be thrown in in time to give them votes; every man of influence who will sell his influence for money or promises, can be secured; every one who can be benefited or injured by the location of line, work shop or station, every one who is looking for contract or favor of any kind, can be set to work; newspapers can be conciliated, orators can be hired, the expenses of meetings can be paid; on the day of election, conveyances can be furnished and whisky and money for such voters as these can tempt can be provided. In a large city, such as San Francisco, besides all these appliances, there is an organized band of ward politicians whose services are always to be secured by money, and if these fail at the polls they can be made effective in another way before the vote is counted.

Ask a San Francisco politician why the Railroad Company lost the subsidy election in June last, and its creatures were compelled to resort to the bungling expedient of changing votes with a lead pencil after they were counted, and he will tell you that the Railroad managers were too confident of success and too niggardly with their money. Instead of giving the “boys” some hard coin, and flinging around a few twenty-dollar pieces as they did at a previous subsidy election, they tried to job the thing out on contingent fees. The “boys,” like Smith of Butte, in the Wardrobe scene, have some prejudice against contingent fees when unaccompanied by anything more tangible, and the Railroad Company “lost by a leetle,” and then made a bad matter worse by bungling in ballot-box stuffing. But the next time they try to carry a subsidy in San Francisco they won't lose by a great deal, unless the popular sentiment against them is very strong indeed, for they will profit by their experience. If they want a million they can ask for a million and a half, and use five hundred thousand, if necessary, to carry the election. That amount of money, united with the other influences which such a powerful company can bring to bear, would carry San Francisco in spite of everything — carry it,not only for a million, but for ten million! Let the Railroad Company but carry the election this year — let them but dictate the nominations, as they hope to do — and with a Governor and a Legislature of their own choosing, San Francisco may thank the mercy of the railroad princes if she don't have to give up bonds to the full amount of five per cent. on her property valuation. They will have the power, if they choose to exercise it, for with them it will be a simple question in arithmetic, and San Francisco must pay the cost of her own plundering.

Talk about trusting the people! Why the people, save in rare conjunctures, are utterly helpless before the power of organized capital, when it has once obtained control, and begins working intelligently towards its ends. Money is all but omnipotent. It can carry primaries, can pack conventions, can bribe Legislatures, elect Judges, subsidize the press, hire bullies, coerce voters, stuff the ballot-boxes. It can leave the people without leaders, and without organization, a defenseless mob, to be coaxed or driven, as may be easiest and cheapest. It may have a very Democratic sound to talk of trusting the people, instead of placing restrictions in the organic law; but the people, if they desire to protect themselves — if they desire to have any voice in public affairs — must keep the temptation of money and the power of money out of political contests as far as possible. Its unavoidable effect is to corrupt, to debauch, to destroy!

Look at the enormous power already wielded by the single great railroad company of California, which the bounty of the General Government, the State, the counties and the city has called into being. Here is a corporation composed of some seven men, owning some fourteen hundred miles of railway, holding over twenty millions acres of land, wielding a capital of hundreds of millions of dollars, with an income which this year cannot fall for short of fifteen millions; with thousands of employés dependent upon it for bread; with other thousands almost as directly dependent upon it through the business which it furnishes or controls; with all the great lines of communication in its hands, and the power to make or mar the fortunes of numbers of influential men in every county through which it passes; with its tools in both political organizations; running its own newspapers for both parties; affiliated closely with banks, express companies, steamship lines, and all the great moneyed institutions, and welding their power with its own whenever it has a point to carry or a political purpose to serve! A corporation, as all corporations, without a soul, but with brains in abundance; gathering into its service and winning to its side, men of the greatest talents and force in every walk of life, from the United States Senator who acts as its agent, the Judge who leaves the Supreme Bench to become its attorney, or the King of the Lobby who can count on his bead-roll a quorum of either House, to the Ward rough who will carry a primary or stuff a ballot-box at its bidding! Compared with a power such as this, all other powers sink into insignificance. Beside its colossal income the revenue of the State seems mean; compared with the patronage it can bestow, the combined patronage of State and Federal Governments in California are trivial. Its arms stretch out in every direction. It has the seven-league boots, the invisible cap, the charmed ring. It can set a thousand wheels working to a common end. Wherever it wants friends or tools it can bend men to its service. For the corrupt it has money; for the ambitious it has promises of support; for the stubborn it has threats, backed by the ability to carry them out.

Can we safely tempt such a power to be continually taking part in our politics? Can we leave the bonds of every county in the State within its grasp, under the flattering delusion that it will wait until the people choose to give them to it? Is it not rather the part of wisdom to remove, while we can, every inducement for it to enter politics — to say to it, once for all, that in no possible way can it usurp the power of taxing the people, and that there is no use in struggling for it? The great fact in the politics of California to-day is the Central Pacific Railroad. No combination can ignore it, and in no calculation can it be left out; and those who know politics best, know best how much meaning there is in the threat that no one who has opposed it can again get a nomination for any office whatever. We must remember, too, that this power, great as it is, is but in its beginnings. A giant to-day, compared with what it was four years ago, it is yet an infant compared with what it will be four years hence, when its now branching transverse lines will reach from one end of the State to the other, and it has swallowed up, as it promises to do, all the transportion companies of the coast.

What is the Democratic Doctrine?

That the doctrine that railroad subsidies should be absolutely forbidden is Democratic doctrine there can be no manner of doubt. Not merely a Democratic doctrine, but the Democratic doctrine — an expression of the essential, distinctive, underlying principle which is the foundation and soul of Democracy — of the principle formulated into the axiom which involves the whole Democratic creed: “THE BEST GOVERNMENT IS THAT WHICH GOVERNS LEAST."

The line drawn on this subsidy question goes to the bed rock. The principle involved is the principle involved in the tariff question, in the currency question, in every great economic question of the day. It is protection vs. free trade; governmental interference vs. individual liberty; special privilege vs. equal rights. And it goes, too, to the very heart and core of our politics. It is centralization against State rights; class government against popular government; aristocracy against democracy.

For it was not merely for the sake of its direct results that Alexander Hamilton proposed, and Jefferson and his followers opposed, that elaborate system of interference with commerce and industry, by means of subsidies and bounties and grants and duties, which the party now dominant in the country has carried to such unheard of lengths. It was because both great minds saw the legitimate effects which such a system would have upon our institutions. The one, profoundly convinced of the inability of the people to govern themselves, regarding the British Constitution as the perfect expression of human wisdom, believing that democratic republicanism such as had been instituted in the United States could lead only to anarchy, yet despairing of at once inaugurating monarchy, sought to build up a colossal money power, whose interests should be completely intertwined with the Government; which would act as a great conservative ruling force, supplying the place of king and aristocracy; and which, dependent upon the Government for the breath of its life, would take the Government into its keeping, and through its forms rule the people. The other, just as profoundly convinced of the ability of the people to govern themselves, just as firmly believing that the truest liberty and the greatest prosperity and happiness could be secured only by republican institutions, saw as clearly that the only way in which those institutions could be maintained was by keeping the functions of government at their minimum; saw that every extension of the field of government lessened the power of the people over it; that every interference of government to encourage this or that branch of trade or industry increased the motive for corruption and the fund at its use.

Here is the genealogy of the two great permanent parties by which the country has been divided since the inception of our Government; here is the meaning of the contests which they have waged over construction and powers; here is the touchstone by which that belonging to the one and that belonging to the other can be infallibly determined!

Let us not mistake. True Democracy seeks to limit the power and functions of all government — not of the Federal Government alone. If it looks with more favor upon the States than upon the Federal Government, and with more favor upon the counties than upon the States, it is because they come closer to the individual, and it is the individual citizen that Democracy seeks to protect, as well from the tyranny of majorities as from any other tyranny; for it has no superstitious reverence for the divine right of majorities. That the majority should rule, is one of its axioms; but it is also its axiom that that rule should be strictly confined to matters in which it is necessary that some one should rule. To take, by taxation, one man's property against his will, and give it to enrich another, is as much a violation of its principles when committed by a county as when committed by the General Government; when sanctioned by a majority vote, as when without that sanction; though in the one case it may apprehend less danger of abuse than in the other.

I quote from what will be recognized as good Democratic authority, the Democratic Review, of 1837, in an article intended as a confession of Democratic faith:

Managing and directing the various general interests of the society, all government is evil and the parent of evil. A strong and active democratic government in the common sense of the term, is an evil differing only in degree and mode of operation, and not in nature, from a strong despotism. The difference is certainly vast, yet inasmuch as these strong governmental powers must be wielded by human agents, even as the powers of despotism, it is, after all, only a difference in degree; and the tendency to demoralization and tyranny is the same, though the development of the evil results is much more gradual and slow in the one case than in the other.... The best government is that which governs least. No human depositories can with safety be trusted with the power of legislation upon the general interests of society so as to operate directly or indirectly on the industry and property of the community. Such power must be perpetually liable to the most pernicious abuse.

Government should have as little as possible to do with the general business and interests of the people. If it once undertake these functions as its rightful province of action it will be impossible to say to it thus far shalt thou go, and no farther. It will be perpetually tampering with private interests, and sending forth seeds of corruption which will result in the demoralization of society. Its domestic action should be confined to the administration of justice, for the protection of the natural equal rights of the citizen and the preservation of social order.... This is the fundamental principle of the philosophy of Democracy: — to furnish a system of administration of justice, and then leave all the business of society to free competition and association — in a word, to the VOLUNTARY PRINCIPLE.... We have endeavored to state the theory of the Jeffersonian Democracy. These are the original ideas of American Democracy, and we would not give much for the practical knowledge which is ignorant of or affects to disregard the essential and abstract principles which really constitute the animating soul of what else were lifeless and naught. The application of these ideas to practice in our political affairs in obvious and simple. Penetrated with a perfect faith in their eternal truth, we can never hesitate as to the direction to which, in every practical case arising, they must point with the certainty of a magnetic needle.

Can we hesitate as to the direction in which these principles point in this question? No! the doctrine enunciated by Governor Haight is indeed the old Democratic doctrine, revived at a time when there exists the most pressing need for its revival.

That railroad subsidies have in many cases been approved by Democratic officers and Democratic majorities is true. But that proves nothing; for, alas! with the great majority of men the dictates of principle are seldom heeded till the evil effects of abandoning it are felt. The strong desire to secure the building of railroads, the glowing anticipations of the benefits which they would bring, have hitherto prevented much inquiry as to the propriety or justice of any plan which promised to hasten the laying of a railroad track. But now that the subsidy system has begun everywhere to develop its true character and bring forth its legitimate results — when it has everywhere degenerated into a system of bald public plunder; into an instrument for robbing the many for the benefit of the few; into a creator of an aristocracy of wealth and a begetter of corporations whose power overshadows all the land; into a fosterer of corruption in every department of government, and a means whereby new means for the robbery of the people under the guise of law may be secured — the time has come when the Democratic party should again assert Democratic principle, and proclaim with every voice it can command: “No more subsidies, on any pretence or for any purpose whatever!"

All the traditions of the Democratic party, all the acts and the utterances of the great statesmen whose names it reveres, point unerringly to the position which it must formally take, and indeed has already practically taken on this subject. Ever the same foe of privilege, ever the enemy of monopoly, ever the upholder of the rights of the individual citizen, the Democratic party, without being false to all its traditions, and abandoning the principles which brought it into being and have continued its existence, cannot fail to take a stand against all subsidies, as involving a doctrine which is the negation of all that it has ever held.

What Subsidies have Given Us.

And surely we may now see whither our departure from Democratic principles is leading us. We are gathering enough of the bitter fruits of governmental interference with industry by subsidies and aids, whether of lands, bonds or protective duties. In spite of the energies of our people, of their marvelous adaptability to all conditions and circumstances, of their wonderful ingenuity in inventing machinery,of the natural wealth of the virgin continent which the Creator has given us, of the gulf stream of hardy workers which Europe pours across the Atlantic — a cry of distress comes up from all quarters. Business is dull, employment is scarce, and wages are low; and while wealth is rapidly accumulating in a few hands, the masses of the people are finding it more and more difficult to live. It is not the burden which the war laid upon us, great though it be, which is doing this; but the legislation by which we are impoverishing the many for the sake of enriching the few. The once busy ship yards of Maine are deserted, the great marine engine works of New York have been turned into warehouses, our commerce has been driven from the ocean, our exports have dwindled to raw material, whole branches of industry have been annihilated and the cost of living has been raised enormously — and this by taxation, imposed, not for revenue, but to give subsidies to privileged rings. Without the slightest return we are paying directly from the Treasury to the National Banks more money than the galling income tax brings in; the public domain — the patrimony of the people, the birthright of the millions yet to come is being given in immense tracts to corporations, while the burden of national taxation is doubled and trebled by taxes imposed upon themselves by States and counties and towns in order to give gratuities to railroad companies.

Our enterprise is withering. The most self-reliant people on

the face of the earth are becoming suppliants for governmental favors

and lobbyists in legislative halls. The American manufacturer, who

could once compete in every market of the world, now begs for a

drawback to enable him to export and a prohibitive duty to enable him

to sell at home; the American ship-builder, whose graceful models were

once the pride of every sea, now asks for a bounty before he can lay a

keel; while not a railroad can be projected without a demand being made

upon the people to pay its cost in subsidies.

The evil is increasing in geometric ratio. For every million acres voted away, comes a demand for ten million more; for every subsidy bill passed, a dozen new ones are introduced. Should there be by chance a meritorious proposition, it is buried out of sight under a mountainous pile of bills which are but bold grabs at the public purse. The subsidy bills before Congress to-day call for about all the land yet left to the General Government, and for enough bonds to pile up a debt almost as large as that made by a year's war; while, if they are passed, the applications next session will be a hundredfold greater.

Yet more evident are the demoralizing effects upon our political system, saturated, as it is, by the corruption bred of subsidies. Look at our party organizations, rendered so corrupt by the “money in politics” that nominations are openly bought and sold, and offices are virtually knocked down to the highest bidder; at our State Legislatures, making laws at the nod of Fisks or Stanfords; at Congress, utterly unable to attend to the most pressing wants of the nation for the clamor of the thousand special interests that besiege it — Congress, whither the giant railroad companies send their Senators, and iron and coal and salt and woolen and whisky rings send their Representatives; where legislation on the most vital and delicate interests of the nation is directed by a hungry, conscienceless lobby; where railroad bonds pay the price of a State's disfranchisement and the plunder of the people is divided in shares of stock!

Is it not time to strike at the root of the evil; to cut off this stream of corruption at it its fountain-head; to reassert a principle which will purify our politics while it lifts the burdens which now oppress our industry?

This matter of county subsidies to railroads may seem a very little thing, but it is the tap root of the Upas tree which is blighting all the land. The principle involved comes home to every man's fireside, for it affects the purchasing power of his labor his personal independence and the comfort of his wife and children.

Let us look the issue fairly in the face. Unless we cast out this corrupting element of special aid and privilege, it is utterly impossible that our republican institutions can long continue to exist. Utterly impossible, because the taxation which it involves will ultimately so impoverish the masses that they must lose their personal independence and moral tone. Utterly impossible, because our system of government must become so inefficient and rotten that it will be buried out of sight with the approbation of gods and men. No amount of cant about the blessings of liberty, no amount of stump buncombe or Fourth of July pyrotechnics, can save it. The American people are not fools, to long hug the shadow of freedom if deprived of its substance; to be long pleased with the empty privilege of putting pieces of paper in a box, when all the thing amounts to is the ratifying of the choice of this or that set of schemers. What will it avail to tell men that they govern themselves, when corporations plunder them at will; to prate of the beauties of the representative system, when the money power buys what legislation it wants; to boast of equality, when the vile and unscrupulous rule the State?

Republicanism, like everything else, has its limitations. The best possible form of government for an intelligent people when confined to its proper sphere, the very sources of its strength become elements of weakness when that sphere is enlarged to include the fostering of special interests. To attempt to moor a man-of-war with a silken thread or to govern an army by the rules of Cushing's Manual, would be as hopeful a task as to carry on paternal government under the forms of republicanism.

Simplify as we may the experiment of self-government, there are difficulties enough in its way. The increasing pressure of population and increasing value of land; the growing inequalities in the distribution of wealth, the rapid rise of overshadowing interests, present difficulties enough, without wantonly complicating the problem. The growing distrust of Legislative power; the growing disposition to strengthen the hands of the Executive as a protection to the people: the deepening doubt in the minds of the thoughtful as to the perpetuity of our institutions; the disregard of Constitutional law; the degradation of the ballot; the perversion and mockery of republican forms in the farce of reconstruction, and the rule of thieves in such cities as New York — all are indications of the strain upon our political system; all warnings that we must come back to first principles if we desire to preserve our institutions to preserve them in their integrity and usefulness, and not as a hollow form.

“This is not a Political Question!”

We are told by the special pleaders of the railroad company that this subsidy question is not a political question; that it will only split and ruin the party that drags it into politics. But if this great question, so deeply affecting every interest of the people — intertwined so closely with our social, industrial and political life — is to be kept out of our politics, to what do our politics amount? Perhaps they will tell us, next, that the tariff is not a political question; that the administration of the finances is not a political question; that the amount and the manner of taxation is something with which parties have no business to interfere! What would they have us do? Are we to still fight over the corpse of slavery; to dispute as whether the war was legal or illegal; to resolve against the alien and sedition laws; to draw party lines on the distinction between tweedledum and tweedledee; to maintain party organizations having for their creed but the voting of the straight ticket, and for their purpose but the putting into office of this or that set of men? — while our masters, the railroad corporations, the land rings, the bank rings, the manufacturing monopolies, plunder us at will, and the corruption they distill penetrates every pore and fibre of our political system until it becomes a disgrace to earth and a reproach to heaven!

Let us Make it a Political Question!

Let us make this issue a political question! The time is ripe for it. The war is six years over; the passions excited by it are cooling fast; men’s minds are coming back to the questions that immediately concern them, and the two permanent parties of the country must again take their places to fight out the old struggle from which the war and the events which preceded and which followed it have diverted attention.

As the old Whig party, the Republican party has become the slave of privilege and the bond-servant of monopoly. It has instituted and still maintains a tariff, the like of which the old Whig party never dreamed of; it has granted away the patrimony of the people, with more recklessness than James or Charles ever granted away the wilds of an unexplored continent; it has created more onerous monopolies upon more frivolous pretexts than ever did Tudor or Stuart; and as a party its feelings are joined and its fortunes are linked with those of the great corporations who have been so successful in obtaining from it license to plunder the people.

Let the Democratic party make the issue with it here; let it reassert its ancient principles, and proclaim in all their fullness the doctrines of free trade and equal rights. Let it have no more of Democratic representatives in Congress announcing themselves protectionists or voting for such infamies as the Northern Pacific Railroad bill, or of Democratic Legislatures granting subsidies to enrich an overgrown corporation. Let it draw the line clearly and sharply, and make opposition to railroad subsidies, to steamship subsidies, to protective duties of every nature, to corporate grants and individual monopolization of public lands, the very condition and test of its membership. Let it do this in California this year, by its nominations and by its platform, and it will sweep the State by an overwhelming majority, as it did on a similar question four years ago. Let it do this in the national contest next year, and the whole power of the Government will infallibly pass into its hands. It may lose some of the old Whigs whom the political perturbations of the last fifteen years have made Democrats by accident; but for this loss it will gain the overwhelming strength which belongs of right to the great party of the people. It will become truly a national party. Under its broad banner of free trade and equal rights the men of New England, now forbidden by law to build ships or to follow the sea, will stand side by side with the men of the South, who have been bound by a ring — ruled Congress that carpet-bag Legislatures might fatten corporations with their substance; the farmers of the West who for years have been voting the Radical ticket, with the whole free trade wing of the Republican party, must join its ranks in solid phalanx. It will indeed have “hitched its wagon to a star.” The forces that move the world will act with it. With its standards will move the chieftains who marshal ideas, and the princes and the prophets of the republic of letters. On its side it will have the great teachers of political economy — living or dead — Adam Smith, Cobden and Mill, Bastiat, Perry and Wells. It will count among its new allies such journals as the Chicago Tribune, the St. Louis Democrat, the New York Post, and the Sacramento Union. It will unite the best thought of the nation with the sure instincts of the great masses.

It will have the money power against it; yet all but omnipotent as that power is in special elections and with Legislatures and Congresses, it cannot maintain itself before the people when a question of principle is directly put.

“In Hoc Signo Vinces!”

When the money power first raised its head to threaten our institutions, it was infinitely less strong and compact than now; but its advances were more insidious. Its political movements were directed by one of the greatest minds that have ever appeared on this continent, aided by men whose proved abilities and eminent services justly entitled them to the confidence of the nation, and its first efforts were even masked by the august form of Washington himself. But no sooner was the question brought fairly before the people than the triumphant election of Thomas Jefferson, in what was long styled “the civil revolution of 1800,” hurled that power to the dust, and at once purged the Government of its heresies. And, afterwards, when a monster corporation, sending its ramifications all through the land, and holding in its hands the finances of the entire Union, grew too great and threatening for the safety of the republic, another uprising of the people came, and another Democratic President seized and throttled the Bank of the United States, though the whole country was convulsed with its dying struggles.

And so it will be again. Though the money power in any or all of its protean shapes may seize upon the machinery of government, may debauch politics and corrupt the representatives of the people; yet so long as the people themselves remain uncorrupted — so long as the great majority of the voters of the United States remain what they are to-day and what they always have been, independent and self-reliant men, asking no favors for themselves and jealously determined to maintain their rights, whenever the evil reaches such a point as to bring it to the comprehension of all, and the question is put fairly and squarely before them for decision, the people of the United States will be found to have the will, as they have the power, to protect themselves and their cherished institutions, come the danger from what quarter and in what shape it may. The party of Jefferson and of Jackson, reasserting its ancient principles, raising again its time-honored banners, casting forth those who are not truly of it, and calling to its ranks again those who have been scattered in the perturbations caused by ephemeral questions, will again unite the masses against special privilege, and again sweep the country as it has time and time before, whenever the issue was one of principle and the battle was fairly joined.

When it comes to pass that this great party of changing names but of fixed principles shall exist no longer; when this Samson, that Jefferson called Republican and Jackson called Democratic, shall be so shorn of its locks by the harlot of corruption that it may be bound without a struggle, then, but not till then, may we well despair of the republic.

But that time is not yet here. From all parts of the State, from all parts of the Union, come indications that the masses of the Democracy are still true in principle, and that they are determined to bring the Government back to its original economy and simplicity, and to make this question of subsidies and protective duties the great issue in the coming canvass.

________

Railroad subsidies, like productive duties, are condemned by the economic principle that the development of industry should be left free to take its natural direction.

They are condemned by the political principle that government should be reduced to its minimum — that it becomes more corrupt and more tyrannical, and less under the control of the people, with every extension of its powers and duties.

They are condemned by the democratic principle which forbids the enrichment of one citizen at the expense of another, and the giving to one citizen of advantages denied to another.

They are condemned by the experience of the whole country, which shows that they have invariably led to waste, extravagance and rascality; that they inevitably become a source of corruption and a means of plundering the people.

The only method of preventing the abuse of subsidies is by prohibiting them altogether. This is absolutely required by the lengths to which the subsidy system in its various shapes has been carried — by the effects which it is producing in lessening the comforts of the masses, stifling industry with taxation, monopolizing land, and corrupting the public service in all its branches.

Should the Democratic party formally take this position, it will but assert its fundamental principle, upon which it has always been victorious, and reinforce itself with the moral sentiment of a nation growing restive under unprecedented taxation.

But it will be said that the Democratic party is opposed to the building of railroads? On the contrary, should the Democratic party carry out its programme of free trade and no subsidies, it will stimulate the building of railroads more than could be done by all the subsidies it is possible to vote. It will at once reduce the cost of building railroads many thousand dollars per mile, by taking off the protective duty now imposed on the iron used; and the stimulus which the reduction of taxation will give to the industry of the whole country will create a new demand for railroads and vastly increase the amount of their business.

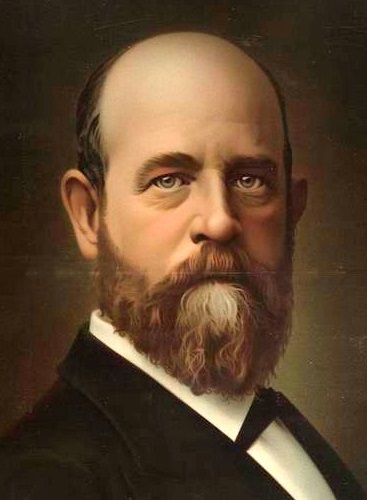

HENRY GEORGE.

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263