The Three Modes Of Production

No introduction or motto supplied for Book III in MS. —H.G., Jr. Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works. |

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

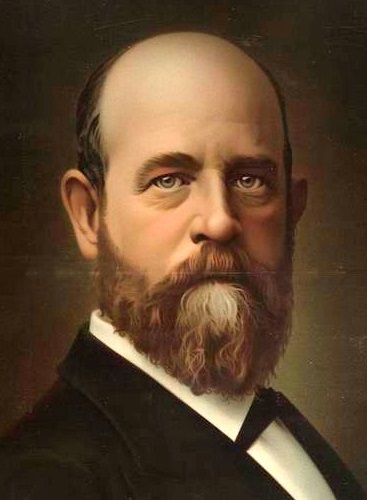

Henry George

|

Production involves change, brought about by conscious will -- Its three modes: (1) adapting, (2) growing, (3) exchanging -- This the natural order of these modes

All production results from human exertion upon external nature, and consists in the changing in place, condition, form or combination of natural materials or objects so as to fit them or more nearly fit them for the satisfaction of human desires. In all production use is made of natural forces or potencies, though in the first place, the energy in the human frame is brought under the direct control of the conscious human will.

But production takes place in different ways. If we run over in mind as many examples as we can think of in which the exertion of labor results in wealth -- either in those primary or extractive stages of production in which what before was not wealth is made to assume the character of wealth; or in the later or secondary stages, in which an additional value or increment of wealth is attached to what has already been given the character of wealth -- we find that they fall into three categories or modes.

The first of these three modes of production, for both reason and tradition unite in giving it priority, is that in which, in the changes he brings about in natural substances and objects, man makes use only of those natural forces and potencies which we may conceive of as existing or manifesting themselves in a world as yet destitute of life; or perhaps it might afford a better illustration to say, in a world from which the generative or reproductive principle of life had just departed, or been by his condition rendered unutilizable by man. These would include all such natural forces and potencies as gravitation, heat, light, electricity, cohesion, chemical attractions and repulsions -- in short, all the natural forces and relations, that are utilized in the production of wealth, below those incident to the vital force of generation.

We can perhaps best imagine such a separation of natural forces by picturing to ourselves a Robinson Crusoe thrown upon a really desert island or bare sand key, in a ship abundantly supplied with marine stores, tools and food so dried or preserved as to be incapable of growth or reproduction. We might also, if we chose, imagine the ship to contain a dog, a goat, or indeed any number of other animals, provided there was no pairing of the sexes. We cannot, in truth, imagine even a bare sand key, in which there should be no manifestation of the generative principle, in insects and vegetables, if not in the lower forms of fish and bird life, but we can readily imagine that our Robinson might not understand, or might not find it convenient, to avail himself of such manifestations of the reproductive principle. Yet without any use of the principle by which things may be made to grow and increase, such a man would still be able to produce wealth, since by changing in place, form or combination what he found already in existence in his island or in his ship, he could fit them to the satisfaction of his desires. Thus he could produce wealth just as De Foe's Robinson Crusoe, whose solitary life so many of us have shared in imagination, produced wealth when he first landed, by bringing desirable things from the wrecked ship to the safety of the shore before destructive gales came on, and by changing the place and form of such of them as were fit for his purpose, making himself a cabin, a boat, sails, nets, clothes, and so on. In the same way, he could catch fish, kill or snare birds, capture turtles, take eggs, and convert the food -- material at his disposal into more toothsome dishes. Thus without growing or breeding anything he could get by his labor a living, until death, or the savages, or another ship came.

For this mode of production, which is mechanical in its nature, and consists in the change in place, form, condition or combination of what is already in existence, it seems to me that the best term is "adapting."

This is the mode of production of the fisherman, the hunter, the miner, the smelter, the refiner, the mechanic, the manufacturer, the transporter; and also of the butcher, the horse-breaker or animal-trainer, who is not also a breeder. We use it when we produce wealth by taking coal from the vein and changing its place to the surface of the earth; and again when we bring about a further increment of wealth by carrying the coal to the place where it is to be consumed in the satisfaction of human desire. We use this mode of production when we convert trees into lumber, or lumber into boards; when we convert wheat into flour, or the juice of the cane or beet into sugar; when we separate the metals from the combinations in which they are found in the ores, and when we unite them in new combinations that give us desirable alloys, such as brass, type -- metal, Babbitt metal, aluminum, bronze, etc.; or when by the various processes of separating and re -- combining we produce the textile fabrics, and convert them again into clothes, sails, bags, etc.; or when by bringing their various materials into suitable forms and combinations, we construct tools, machines, ships or houses. In fact, all that in the narrower sense we usually call "making," or, if on a large scale, "manufacturing," is brought about by the application of labor in this first mode of production -- the mode of "adapting."

In the Northwest, however, they speak sometimes of "manufacturing wheat;" in the West of "making hogs," and in the South of "making cotton" (the fiber) or "making tobacco" (the leaf). But in such local or special sense the words manufacturing or making are used as equivalent to producing. The sense is not the same, nor is the suggested action in the same mode, as when we properly speak of flour as being manufactured, or of bacon, cotton cloth or cigars being made. Wonderful machines are indeed constructed by man's power of adaptation. But no extension of this power of adaptation will enable him to construct a machine that will feed itself and produce its kind. His power of adapting extended infinitely would not enable him to manufacture a single wheat-grain that would sprout, or to make a hog, a cotton-boll or a tobacco-leaf. The tiniest of such things are as much above man's power of adapting as is the "making" of a world or the "manufacture" of a solar system.

There is, however, another or second mode of production. In this man utilizes the vital or reproductive force of nature to aid him in the producing of wealth. By obtaining vegetables, cuttings or seeds, and planting them; by capturing animals and breeding them, we are enabled not merely to produce vegetables and animals in greater quantity than Nature spontaneously offers them to our taking, but, in many cases, to improve their quality of adaptability to our uses. This second mode of production, the mode in which we make use of the vital or generative power of nature, we shall, I think, best distinguish from the first, by calling it "growing." It is the mode of the farmer, the stock-raiser, the florist, the bee-keeper, and to some extent at least of the brewer and distiller.

And besides the first mode, which we have called "adapting," and the second mode, which we have called "growing," there is still a third mode in which, by men living in civilization, wealth is produced. In the first mode we make use of powers or qualities inherent in all material things; in the second we make use of powers or qualities inherent in all living things, vegetable or animal. But this third mode of production consists in the utilization of a power or principle or tendency manifested only in man, and belonging to him by virtue of his peculiar gift of reason -- that of exchanging or trading.

That it is by and through his disposition and power to exchange, in which man essentially differs from all other animals that human advance goes on, I shall hereafter show. Yet not merely is it through exchange that the utilization in production of the highest powers both of the human factor and the natural factor becomes possible, but it seems to me that in itself exchange brings about a perceptible increase in the sum of wealth, and that even if we could ignore the manner in which it extends the power of the other two modes of production, this constitutes it, in itself, a third mode of production. In the Yankee story of the two school-boys so [a]cute at a trade that when locked in a room they made money by swapping jack-knives, there is the exaggeration of a truth. Each of the two parties to an exchange aims to get, and as a rule does get, something that is more valuable to him than what he gives -- that is to say, that represents to him a greater power of labor to satisfy desire. Thus there is in the transaction an actual increase in the sum of wealth, an actual production of wealth. A trading-vessel, for instance, penetrating to the Arctic, exchanges fish-hooks, harpoons, powder and guns, knives and mirrors, green spectacles and mosquito-nets for peltries. Each party to the exchange gets in return for what costs it comparatively little labor what would cost it a great deal of labor to get by either of the other modes of production. Each gains by the act. Eliminating transportation, which belongs to the first mode of production, the joint wealth of both parties, the sum of the wealth of the world, is by the exchange itself increased.

This third mode of production let us call "exchanging." It is the mode of the merchant or trader, of the storekeeper, or as the English who still live in England call him, the shopkeeper; and of all accessories, including in large measure transporters and their accessories.

We thus have as the three modes of production:

(1) Adapting;

(2) Growing;

(3) Exchanging.

These modes seem to appear and to assume importance in the development of human society much in the order here given. They originate from the increase of the desires of men with the increase of the means of satisfying them under pressure of the fundamental law of political economy, that men seek to satisfy their desires with the least exertion. In the primitive stage of human life the readiest way of satisfying desires is by adapting to human use what is found in existence. In a later and more settled stage it is discovered that certain desires can be more easily and more fully satisfied by utilizing the principle of growth and reproduction, as by cultivating vegetables and breeding animals. And in a still later period of development, it becomes obvious that certain desires can be better and more easily satisfied by exchange, which brings out the principle of cooperation more fully and powerfully than it could obtain among unexchanging economic units.

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263