What Smith Meant By Wealth

Epigraphs to Book IIDefinitions are the basis of systematic reasoning. — Aristotle The mixture of those things by speech which are by nature divided is the mother of all error. — Hooker Bacon made us sensible of the emptiness of the Aristotelian philosophy; Smith, in like manner, caused us to perceive the fallaciousness of all the previous systems of political economy; but the latter no more raised the superstructure of this science, than the former created logic.... We are, however, not yet in possession of an established text-book on the science of political economy, in which the fruits of an enlarged and accurate observation are referred to general principles that can be admitted by every reflecting mind; a work in which these results are so complete and well arranged as to afford to each other mutual support, and that many everywhere and at all times be studied with advantage. — J.B. Say, 1803 We may cite as examples of such inchoate but yet incomplete discoveries the great Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith — a work which still stands out, and will ever stand out, as that of a pioneer, and the only book on political economy which displays its genius to every kind of intelligent reader. But among the specialists and the schools, this work of genius which swayed all Europe in its day, is laid upon the shelf as an antiquated affair, superseded by the smaller and duller men who have pulled his system to pieces and are offering us the fragments as a science most of whose first principles are still under dispute. — Professor (Greek) J.P. Mahaffy, "The Present Position of Egyptology," "Nineteenth Century," August, 1894. Putting this book online was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works. |

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

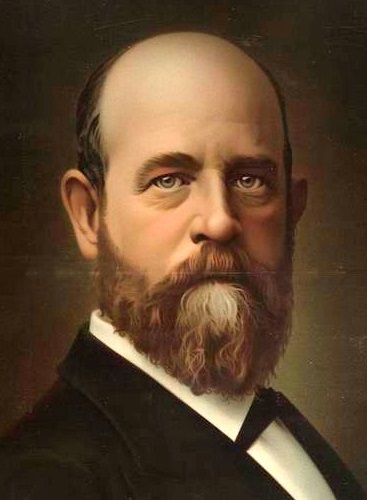

Henry George

|

Significance of the title Wealth of Nations — Its origin shown in Smith's reference to the Physiocrats — His conception of wealth in his introduction — Objection by Malthus and by Macleod — Smith's primary conception that given in Progress and Poverty — His subsequent confusions

If, considering the increasing indefiniteness among professed economists as to the nature of wealth, we compare Adam Smith's great book with the treatises that have succeeded it, we may observe on its very title-page something usually unnoticed, but really very significant. Adam Smith does not propose an inquiry into the nature and causes of wealth, but "an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations."

The words I here italicize have become the descriptive title of the book. This is known, not as "Adam Smith's Inquiry," or "Adam Smith's Wealth," but as Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations. Yet these limiting words, "of nations," seem to have been little noticed and less understood by the writers who in increasing numbers for almost a hundred years have taken this great book as a basis for their elucidations and supposed improvements. Their assumption seems to be that it is wealth generally or wealth without limitation which Adam Smith treats of and which is the proper subject of political economy, and that if he meant anything by his determining words "of nations," he referred to such political divisions as England, France, Holland, etc.

Some superficial plausibility is perhaps given to this view from the fact that one of the divisions of the Wealth of Nations, Book III, is entitled "Of the Different Progress of Opulence in Different Nations," and that in it illustrative reference is made to various ancient and modern states. But that in his choice of the limiting words "of nations" as indicating the kind of wealth into the nature and causes of which he proposed to inquire, Adam Smith referred to something other than the political divisions of mankind called states or nations, is sufficiently clear.

While he is, as I have said, not very definite and not entirely consistent in his use of the term wealth, yet it is certain that what he meant by "the wealth of nations," of the nature and causes of which he proposed to inquire, was something essentially different from what is meant by wealth in the ordinary use of the word, which includes as wealth everything that may give wealthiness to the individual considered apart from other individuals. It was that kind of wealth the production of which increases and the destruction of which decreases the wealth of society as a whole, or of mankind collectively, which he sought to distinguish from the word "wealth" in its common or individual sense by the limiting words, "of nations," in the meaning not of the larger political divisions of mankind, but of societies or social organisms.

In the body of the Wealth of Nations there occurs again the phrase which furnished Adam Smith the title for his ten years' work. In Book IV, speaking of those members of "the French republic of letters" who at that time called themselves and were called "Economists," but who have been since distinguished from other economists, real or pretended, by the name of Physiocrats,* — a school who might be better still distinguished as the Single Taxers of the Eighteenth Century, he says (the italics are mine):

This sect, in their works, which are very numerous, and which treat not only of what is properly called political economy, or of the nature and causes of the wealth of nations,

but of every other branch of the system of civil government, all follow implicitly, and without any sensible variation, the doctrines of Mr. Quesnai.

This recognition of the fact that, not wealth in the loose and common sense of the word, but that which is wealth to societies considered as wholes, or as he phrased it, "the wealth of nations," is the proper subject-matter of what is properly called political economy — shows the origin of the title Adam Smith chose for his book. He had doubtless thought of calling it a "Political Economy," but either from the consciousness that his work was incomplete, or from the modesty of his real greatness, finally preferred the less pretentious title, which expressed to his mind the same idea, "An inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations."

It has been much complained of Adam Smith that he does not define what he means by wealth. But this has been exaggerated. In the very first paragraph of the introduction to his work he thus explains what he means by the wealth of nations, the only sense of the word wealth which it is the business "of what is properly called political economy" to consider:

The annual labor of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes, and which consist always either in the immediate produce of that labor, or in what is purchased with that produce from other nations.

Again, in the last sentence of this introduction he speaks of "the real wealth, the annual produce of the land and labor of the society." And in other places throughout the book he also speaks of this wealth of society or wealth of nations, or real wealth, as the produce of land and labor.

What he meant by the produce of land and labor was of course not the produce of land plus the produce of labor, but the joint produce of both — that is to say: the result of labor, the active factor of all production, exerted upon land, the passive factor of all production, in such a way as to fit it (land or matter) for the gratification of human desires. Malthus, indorsed by McCulloch and a long line of commentators upon Adam Smith, objects to his definition that "it includes all the useless products of the earth, as well as those which are appropriated and enjoyed by man." And in the same way Macleod, a recent writer whose ability to say clearly what he wants to say makes his Elements of Economics, despite its essential defects, a grateful relief among economic writings, objects that if —

the annual produce of land and labor, either separately or combined, is wealth, then every useless product of the earth is wealth, as well as the most useful — the tares as well as the wheat. If a diver fetch a pearl oyster from the deep sea, the shell is as much the "produce of land and labor" as the pearl itself. So if a nugget of gold or a diamond is obtained from a mine, the rubbish it is found in and brought up with is as much the "produce of land and labor" as the gold or the diamond; and innumerable instances of this sort may be cited.

The communication of thought by speech would be at an end if Adam Smith could be asked to explain that the produce of labor means what the labor is exerted to get, not what it is incidentally obliged to remove in the process of getting that. Yet most of the complaints of his failure to say what he means by wealth have no better basis than these objections.

In truth whoever will attend to the obvious meaning of the word he uses will see that what Adam Smith meant by "the wealth of nations" or wealth in the sense it is to be considered in "what is properly called political economy," is in reality what in the chapter of Progress and Poverty entitled "The Meaning of the Terms" (Book I, Chapter II) is given as the proper meaning of the economic term — namely, that of "natural products that have been secured, moved, combined, separated, or in other ways modified by human exertion, so as to fit them for the gratification of human desires."

Through the first and most important part of his work, this is the idea which Smith has constantly in mind and to which he constantly adheres in tracing all production of wealth to labor. But having grasped this idea of the nature of wealth without having clearly defined its relation to other ideas still lying in his mind, he falls into the subsequent confusion of also classing personal qualities and debts as wealth.

* From physiocratie, or government in the nature of things, or natural order, a name suggested, in 1768, by Dupont de Nemours, one of the most active of their number.

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263