Man's Powers Extended

Epigraph to Book IThough but an atom midst immensity, - Bowring's translation of Dershavin This book was transcribed into shtml by Dan Sullivan, and was underwritten by The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, publisher of Henry George's works.

|

Saving Communities

|

||||||

Home |

Site Map |

Index

|

New Pages |

Contacts |

|

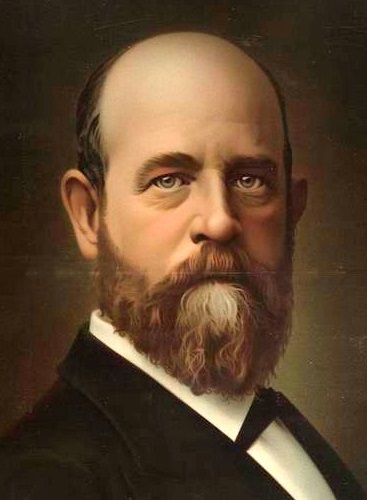

Henry George

|

Extensions of man's powers in civilization - Due not to improvement in the individual but in the society - Hobbes's Leviathan - The Greater Leviathan - This capacity for good also capacity for evil.

Man, as we have any knowledge of him,

either in the present or in the

past, is always man; differing from other animals in the same way,

feeling the same essential needs, moved by the same essential desires,

and possessed of the same essential powers.

Yet between man in the lowest savagery and man in the highest civilization how vast the difference in the ability of satisfying these needs and desires by the use of these powers. In food, in raiment, in shelter; in tools and weapons; in ease of movement and of transportation; in medicine and surgery; in music and the representative arts; in the width of his horizon; in the extent and precision of the knowledge at his service - the man who is free to the advantages of the civilization of today is as a being of higher order compared to the man who was clothed in skins or leaves, whose habitation was a cave or rude hut, whose best tool a chipped flint, whose boat a hollowed log, whose weapons the bow and arrows, and whose horizon was bounded, as to the past, by tribal tradition, and as to the present by the mountains or sea-shore of his immediate home and the arched dome which seemed to him to shut it in.

But if we analyze the way in which these extensions of man's power of getting and making and knowing and doing are gained, we shall see that they come, not from changes in the individual man, but from the union of individual powers. Consider one of those steamships now crossing the Atlantic at a rate of over five hundred miles a day. Consider the cooperation of men in gathering knowledge, in acquiring skill, in bringing together materials, in fashioning and managing the whole great structure; consider the docks, the storehouses, the branching channels of trade, the correlation of desires reaching over Europe and America and extending to the very ends of the earth, which the regular crossing of the ocean by such a steamship involves. Without this cooperation such a steamship would not be possible.

There is nothing whatever to show that the men who today build and navigate and use such ships are one whit superior in any physical or mental quality to their ancestors, whose best vessel was a coracle of wicker and hide. The enormous improvement which these ships show is not an improvement of human nature; it is an improvement of society - it is due to a wider, fuller union of individual efforts in the accomplishment of common ends.

To consider in like manner any one of the many and great advances which civilized man in our time has made over the power of the savage, is to see that it has been gained, and could only have been gained, by the widening cooperation of individual effort.

The powers of the individual man do not indeed reach their full limit when maturity is once attained, as do those of the animal; but, the highest of them at least, are capable of increasing development up to the physical decay that comes with age, if not up to the verge of the grave. Yet, at best, man's individual powers are small and his life is short. What advances would be possible if men were isolated from each other and one generation separated from the next as are the generations of the seventeen-year locusts? The little such individuals might gain during their own lives would be lost with them. Each generation would have to begin from the starting-place of its predecessor.

But man is more than an individual. He is also a social animal, formed and adapted to live and to cooperate with his fellows. It is in this line of social development that the great increase of man's knowledge and powers takes place.

The slowness with which we attain the ability to care for ourselves and the qualities incident to our higher gifts involve an overlapping of individuals that continues and extends the family relation beyond the limits which obtain among other mammalia. And, beyond this relation, common needs, similar perceptions and like desires, acting among creatures endowed with reason and developing speech, lead to a cooperation of effort that even in its crudest forms gives to man powers that place him far above the beasts and that tends to weld individual men into a social body, a larger entity, which has a life and character of its own, and continues its existence while its components change, just as the life and characteristics of our bodily frame continue, though the atoms of which it is composed are constantly passing away from it and as constantly being replaced.

It is in this social body, this larger entity, of which individuals are the atoms, that the extensions of human power which mark the advance of civilization are secured. The rise of civilization is the growth of this cooperation and the increase of the body of knowledge thus obtained and garnered.

Perhaps I can better point out what I mean by an illustration:

The famous treatise in which the English

philosopher Hobbes, during the

revolt against the tyranny of the Stuarts in the seventeenth century,

sought to give the sanction of reason to the doctrine of the absolute

authority of kings, is entitled Leviathan.

It thus begins:

Nature, the art whereby God hath made and governs the world, is by the art of man, as in many other things, so in this also imitated, that it can make an artificial animal.... For by art is created that great Leviathan called a commonwealth or state, in Latin civitas, which is but an artificial man; though of greater stature and strength than the natural, for whose protection and defense it was intended; and in which the sovereignty is an artificial soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body; the magistrates and other officers of judicature and execution, artificial joints; reward and punishment, by which fastened to the seat of the sovereignty every joint and member is moved to perform his duty, are the nerves, that do the same in the body natural; the wealth and riches of all the particular members, are the strength; salus populi, the people's safety, its business; counselors by whom all things needful for it to know are suggested unto it, are the memory; equity and laws, an artificial reason and will; concord, health; sedition, sickness; and civil war, death. Lastly, the pacts and covenants, by which the parts of this body politic were at first made, set together, and united, resemble that fiat, or the "Let us make man," pronounced by God in the creation.

Without stopping now to comment further on Hobbes's suggestive analogy, there is, it seems to me, in the system or arrangement into which men are brought in social life, by the effort to satisfy their material desires - an integration which goes on as civilization advances - something which even more strongly and more clearly suggests the idea of a gigantic man, formed by the union of individual men, than any merely political integration.

This Greater Leviathan is to the political structure or conscious commonwealth what the unconscious functions of the body are to the conscious activities. It is not made by pact and covenant, it grows; as the tree grows, as the man himself grows, by virtue of natural laws inherent in human nature and in the constitution of things; and the laws which it in turn obeys, though their manifestations may be retarded or prevented by political action are themselves utterly independent of it, and take no note whatever of political divisions.

It is this natural system or arrangement, this adjustment of means to ends, of the parts to the whole and the whole to the parts, in the satisfaction of the material desires of men living in society, which, in the same sense as that in which we speak of the economy of the solar system, is the economy of human society, or what in English we call political economy. It is as human units, individuals or families, take their place as integers of this higher man, this Greater Leviathan, that what we call civilization begins and advances.

But in this as in other things, the capacity for good is also capacity for evil, and prejudices, superstitions, erroneous beliefs and injurious customs may in the same way be so perpetuated as to turn what is the greatest potency of advance into its greatest obstacle, and to engender degradation out of the very possibilities of elevation. And it is well to remember that the possibilities of degradation and deterioration seem as clear as the possibilities of advance. In no race and at no place has the advance of man been continuous. At the present time, while European civilization is advancing, the majority of mankind seem stationary or retrogressive. And while even the lowest peoples of whom we have knowledge show in some things advances over what we infer must have been man's primitive condition, yet it is at the same time true that in other things they also show deteriorations, and that even the most highly advanced peoples seem in some things below what we best imagine to have been as the original state of man.

Comments:

Saving Communities

420 29th Street

McKeesport, PA 15132

United States

412.OUR.LAND

412.687.5263